by Brooks Riley

‘Every situation in life, indeed every moment, is of infinite value, because it represents an entire eternity.’ –Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

It seems we’re always tinkering with those eternities, not just to cherish their value or find their meaning, but to transform them into something else. Maybe that’s what creative writing ultimately is—momentary eternities arranged so that they somehow move the reader the way a perfect arrangement of musical notes might do. Reading is a compelling pastime for millions because words function as artfully selected indicators of events and images that readers will complete in their own minds, as they follow verbal guideposts for the imagination to begin to do its work.

It seems we’re always tinkering with those eternities, not just to cherish their value or find their meaning, but to transform them into something else. Maybe that’s what creative writing ultimately is—momentary eternities arranged so that they somehow move the reader the way a perfect arrangement of musical notes might do. Reading is a compelling pastime for millions because words function as artfully selected indicators of events and images that readers will complete in their own minds, as they follow verbal guideposts for the imagination to begin to do its work.

‘The dog is brown’ will evoke as many different brown dogs as there are readers of that sentence. But even a more exacting description of a short brown dog with silky fur that catches the light will conjure up a variety of imagined brown canines with silky fur, enough to fill a kennel. In every piece of writing, there will always be ellipses that can be filled in only by the reader’s imagination, which acts like spilled water, spreading into every dry nook and cranny along its path, its wetness both a nourishment and an added dimension. A book is a writer’s covenant with the reader’s imagination. Together they complete the work.

What authors create for their readers are metaverses. They’ve been carefully fashioned and made accessible to anyone who cares to traverse them, in the same way that the viewer of a movie enters a carefully prepared visual environment. Whether content plays out on a monitor or in the mind’s eye, the second-life reality of an invented world has already been here for a long time. For non-readers, movies and television offer the same kind of metaversal immersion.

***

A metaverse of one’s own is a different experience. It emerges solely from the wishful thinking of a daydreamer weaving an imaginary tale, taking an imaginary trip to an exotic place, or building a dream house. What happens in that metaverse is up to the daydreamer’s discretion, a homemade environment with or without narrative. For years, whenever I felt depressed, I designed a small modern house with an atrium at its center—sketching crude blueprints of it, completing it only in my mind. In no time I felt better—except for the lingering wish to actually build such a house. One day I realized, I don’t need to build that house. I live there already. I had lived there since the moment I conceived it.

***

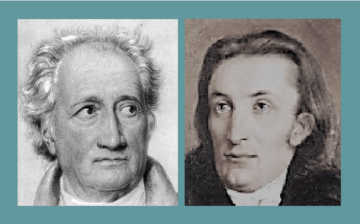

I stumbled across Goethe’s quote at the beginning of my summer with him, an unexpectedly delightful encounter made possible through the good graces of one Johann Peter Eckermann, a young writer who worked closely with the elderly Goethe during the last ten years of his life. His book, Conversations with Goethe became my seasonal metaverse of choice, a time and place to dive into for as long as it lasted—no VR goggles required.

I stumbled across Goethe’s quote at the beginning of my summer with him, an unexpectedly delightful encounter made possible through the good graces of one Johann Peter Eckermann, a young writer who worked closely with the elderly Goethe during the last ten years of his life. His book, Conversations with Goethe became my seasonal metaverse of choice, a time and place to dive into for as long as it lasted—no VR goggles required.

I had planned to go to Weimar anyway, a tarnished gem of a town I cherish above most others. In keeping with my pandemic lockdown adventures, I went there without leaving home. The Weimar of today is a place I know well, having done work at the Deutsches Nationaltheater one summer. But this time, I didn’t just want to go to Weimar, I wanted to go to a different century—to the later years of Goethe and his supporting cast—among others, son August and daughter-in-law Ottilie; best friend Karl August, the progressive and much loved Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach; drop-by intellectual brothers von Humboldt; and the former musical child prodigy Johann Nepomuk Hummel—a time when the Nationaltheater was just a busy Court Theater, presenting a different play or opera every night.

Goethe is not the first dead person I’ve spent time with. Of all the possible candidates for an excursion into a literary metaverse, he would not be my first choice. He wouldn’t even have made the dinner party list every writer interviewed by the New York Times is asked to imagine. I resented the way he dismissed young Schubert, who immortalized two Goethe poems at the age of 17. I didn’t like his conservatism, or his disapproval of the Grand Duke’s liberal constitution for Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach—a first among the German states. I was suspicious of the cultish devotion Goethe engendered in so many, including George Eliot and Thomas Carlyle. I imagined him descending into his dotage surrounded by fans and sycophants.

I was wrong, as I found out from Eckermann, who was more than obliging in letting me into that room where he and Goethe conversed about nearly everything. To help me in my process of eavesdropping, I took a video tour of Goethe’s house to get an idea of where they might have been sitting, (Imagination flourishes in visualized settings.), a tour that helped me enjoy a party at Goethe’s house…the mood very free and informal; people stood or sat, joking, laughing, talking to all and sundry, just as the fancy took them…Goethe himself was a most gracious presence at the party, circulating constantly; he seemed to prefer listening, and letting his guests talk, rather than saying much himself.

Eckermann’s appearance in 1823 was fortuitous from Goethe’s point of view, gifting the old writer with a youthful sounding board to offset his dwindling circle of contemporaries and peers. With Eckermann, a struggling poet from a working-class background, Goethe could feel at ease. He also needed someone to edit his early writings. It could be said that Goethe took unfair advantage of Eckermann, not paying him a salary. But if he had, the intense friendship might not have survived the subtle barriers of an employer-employee relationship. Goethe remunerated Eckermann in other ways, finding a publisher for his first collection of critical essays, and work as tutor and librarian. Goethe immediately brought him into the family circle and introduced him to the movers and shakers of cozy Weimar (population ca.9000).

Reading Conversations with Goethe, I came to know Goethe the mensch—curious about everything, kind, funny, affectionate, loyal. Opinionated, but never mean. Meeting him through the prism of Eckermann’s intriguing recreations of their time together—being in the room with them—I discovered a man who was well aware of his sell-by date, but genuinely interested in passing along what he’d learned about the writing process to a younger generation, especially what he’d learned from his mistakes—the perfect MFA writer’s workshop guide.

Whatever subject they talked about, Goethe treated Eckermann as a peer. And Eckermann, whose education had been hard won, was a confident interlocutor, always probing, and encouraging him to go back to the works he had abandoned, notably the second part of Faust. The high regard and respect they held for each other reveals a side of Goethe I had never expected.

Eckermann lets Goethe do most of the talking, but as a man of taste and opinions himself, Eckermann doesn’t hesitate to offer his own take on a subject. There’s an equanimity of spirit in these conversations that reveals a deep emotional bond between the two and mutual trust. Goethe is rejuvenated by their conversations, and inspired to write again. Their rare moments of discord expose Goethe’s deep-seated insecurity about his scientific work: Eckermann could say anything about Goethe’s literary output, but his persistent questioning of certain aspects of the Farbenlehre (Theory of Color) offended Goethe.

My metaverse in Weimar was full of joy and surprises, laughter and a few tears. I learned so much. I took walks with Eckermann and Goethe to the Gartenhaus which Grand Duke Karl August had given Goethe years earlier, rose vines still climbing espaliers on all sides. I went inside to the room where Goethe had escaped to write in earlier days. I marveled at the red kitchen, fit for concocting a witch’s brew. Together with Goethe, tears in his eyes, I read Alexander von Humboldt’s letter describing the final days of the Grand Duke, marred by his feverish compulsion to get answers to scientific questions. Along with Goethe, I was fascinated by Eckermann’s account of attempting to construct a bow, a trial-and-error effort involving many different types of wood and cutting methods. When the two later shot a few arrows in the back garden, I watched.

***

Metaverses created by authors and their fictions or reportages provide spaces for the reader to enter them, to be there without being seen, without interacting in any way. ‘Fly on the wall’ is a belabored term, and it’s not accurate. In my Weimar episode, I walked beside them when they went somewhere. I saw what they saw. I sat at the small table as they conversed. In the end, I followed Eckermann into the room where he viewed Goethe for the last time. I was more a silent witness than a fly.

Horizon, the metaverse Mark Zuckerberg wants Meta to create, is interactive, but it won’t be you who interacts. It will be your avatar, a second you (as if one wasn’t enough). Horizon is trying to build a wedge between you and real life, in a process that ultimately unreals you, implying that your avatar is the only one who can have fun, or live in imagined luxury–all the cringeworthy, soul-draining visions of hell presented by Zuckerberg’s video introduction to his dubious enterprise. It will be hard work for you to give that avatar the life you want, along with pricey items of AR clothing, art and furnishings. Then what? You’ll remove those VR headsets, wipe away the sweat around your eyes, and wonder what to do next for entertainment.

To give Zuckerberg some slack (understanding the pressure he’s under from shareholders to deliver the next big thing), I tried to imagine a Horizon-staged three-way conversation between Goethe, Eckermann and me, fashioning three avatars and sitting them down in a VR version of that room on the Frauenplan in Weimar. It’s not that I wouldn’t want to have such a conversation, it’s that I’d have to invent it myself, and then stage it. That’s no fun for me, because then I’d already know what they’d say.

Far more tempting—if impossible—is the thought of bringing the boys from Weimar to the present day, and showing them what the World Wide Web, Horizon and Meta are up to. But that’s a metaverse of my own, which I’ll keep to myself.

***

The Penguin edition of Conversations with Goethe is a welcome new translation by Allan Blunden, with an excellent introduction by Ritchie Robertson.