by Thomas R. Wells

The recent history of the term ‘political correctness’ and its association with the contemporary left and the tedious culture wars obscures its true character and ubiquity. Political correctness is real, significant, and arguably the dominant mode of politics since before humans could even talk. It is the few trying to rule over the many by persuading the many that they are the ones in the minority.

The recent history of the term ‘political correctness’ and its association with the contemporary left and the tedious culture wars obscures its true character and ubiquity. Political correctness is real, significant, and arguably the dominant mode of politics since before humans could even talk. It is the few trying to rule over the many by persuading the many that they are the ones in the minority.

The goal of this form of politics is the manufacturing and maintaining of something called ‘pluralistic ignorance‘ where members of a group mistakenly believe that most other members disagree with them. As a result, a well-positioned minority is able to persuade the group as a whole of the existence of a fictitious shared consensus supporting their rule or values. Taken separately, many individuals may recognise that they don’t agree with what is being done in their name. But at the same time they believe they are the only one (or one of a very few) who think this, and so they go along with the thing they disagree with.

How is this rule of the few established and maintained? It is essential that the majority never realise that their views are in the majority, or they will withdraw the grudging allegiance on which the minority’s precarious rule relies. Therefore on certain issues, silence must fall. By one means or another, members of the majority must be dissuaded from speaking truthfully about what they believe in places where others might hear them, believe them, and say ‘Yes – me too!’ For such a cascade of personal disclosures would quickly unravel the delicate fabric of the fictional consensus. Read more »

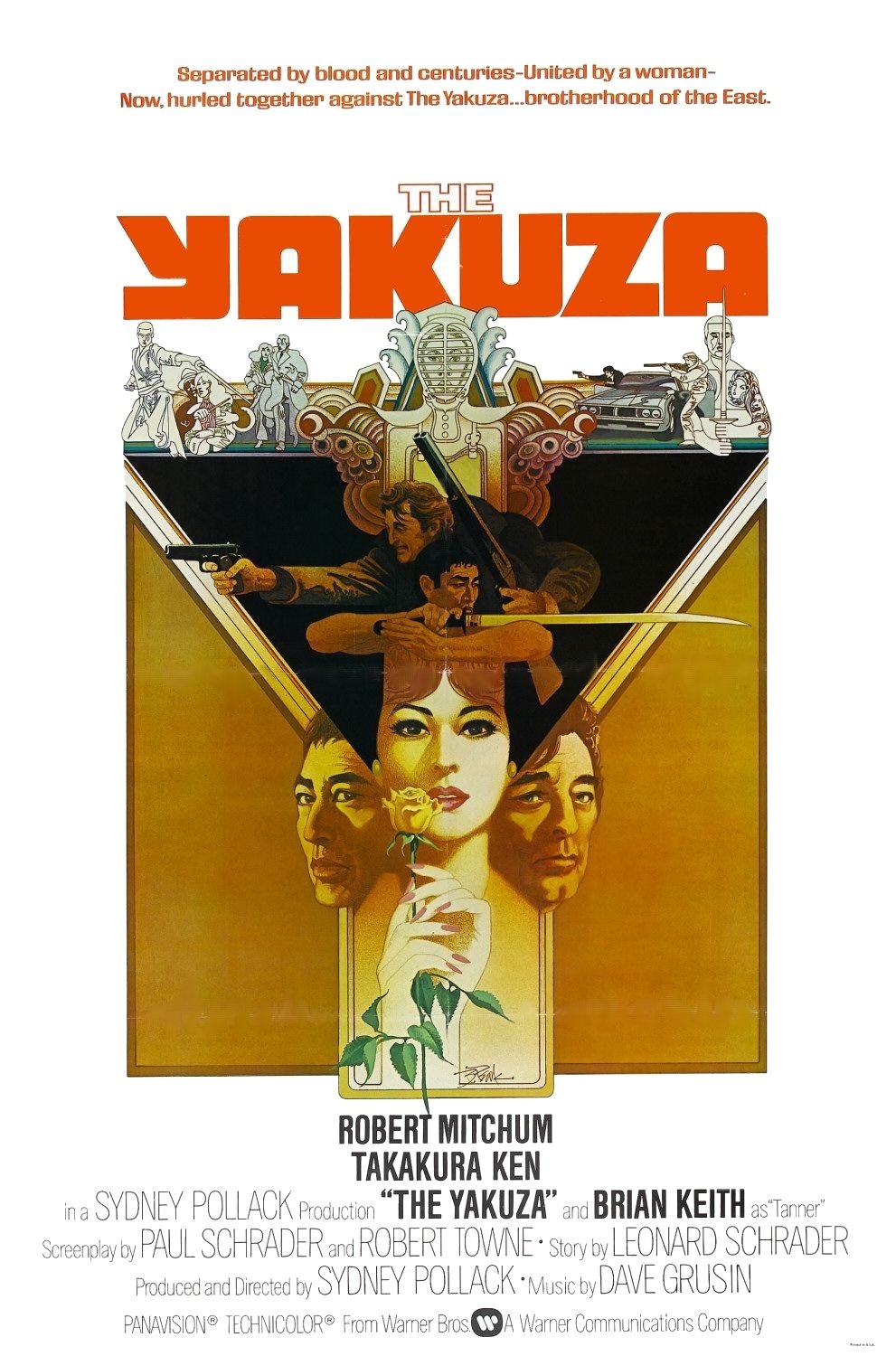

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

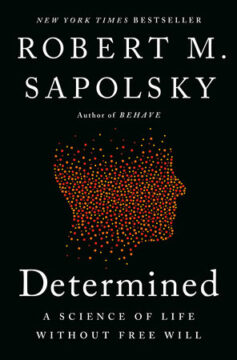

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza. A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

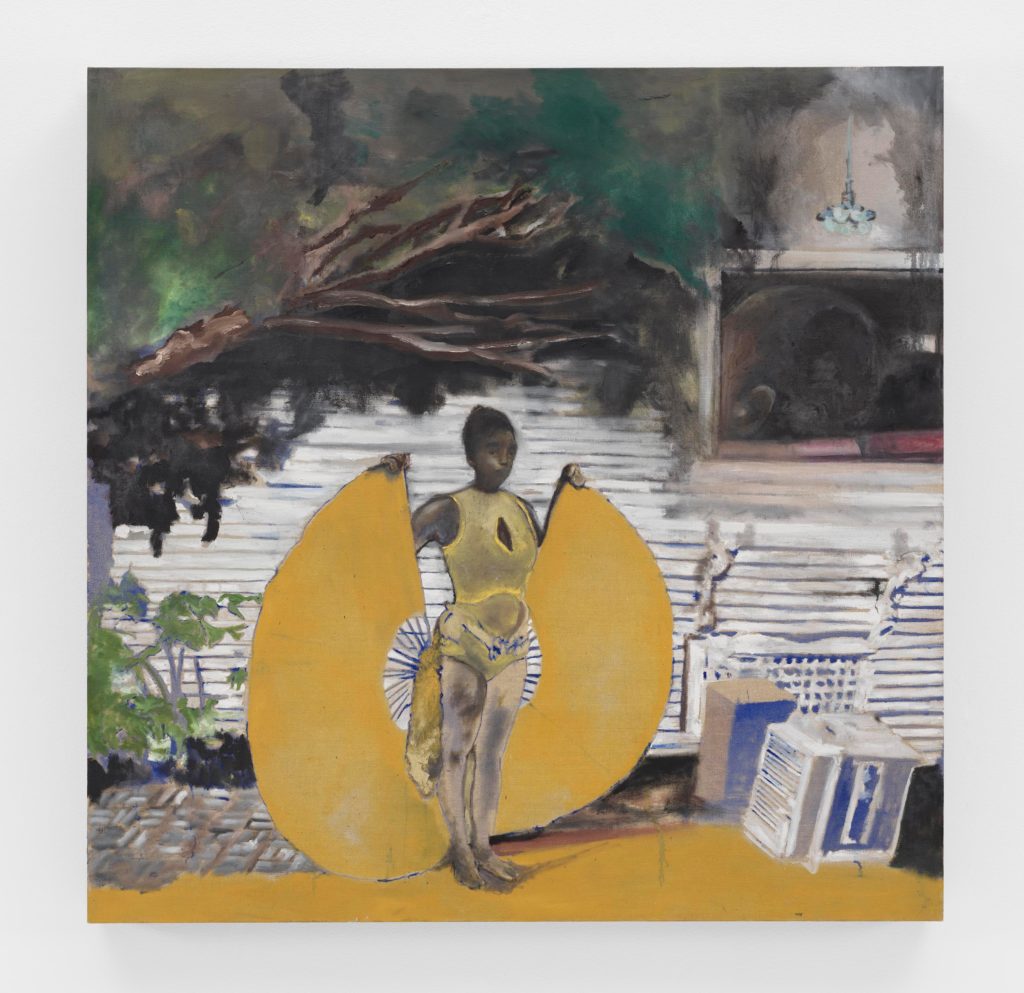

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

What do we know about vampires?

What do we know about vampires?

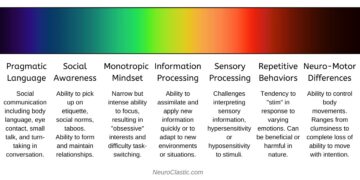

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of  What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at  I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial

I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial