by Martin Butler

My favourite lesson in secondary school played no part in my future career but nevertheless enriched my life immeasurably. Despite being a sleepy rural school very low down the pecking order it had fully equipped woodwork and metalwork workshops. Woodwork was my favourite subject by far. This was in the days when there was a gender split – girls doing something called ‘domestic science’ while the boys did woodwork and metalwork. Woodwork lessons were very straightforward. The teacher – Mr Carpenter (can you believe!) – would demonstrate standard joints, starting with a simple halving joint, and then we would each go to our benches and have a go at producing something as near as possible to what he had produced. By the end of the first year we were making half-blind dovetails which require considerable care and precision. All done with hand tools alone. Once we had mastered the basic joints, we were free to make whatever we wanted. Along with art and sport it was one of the few subjects in which it was possible to excel without having to write anything down, which for me was a blessing. Of course, we would sketch out plans, but these were always very provisional and often bore little resemblance to the final product. You were judged on the product alone, not on your workings.

Mr Carpenter told us that in maths if you got 9 out of 10 it was pretty good, but in woodwork if 9 out of ten joints were good and the 10th bad, your creation was likely to fall to pieces. The laws of physics ruled. As with other crafts, woodwork requires patience and practice. Wood makes demands that have to be met if you are going to produce anything worthwhile, imposing a kind of natural discipline that comes not from some authority figure but from the physical world itself. The digital world is binary, you either know the right clicks to make, the right options to pick on a drop-down menu, or you don’t. In contrast, hand-crafts are essentially qualitative. Read more »

In

In  Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

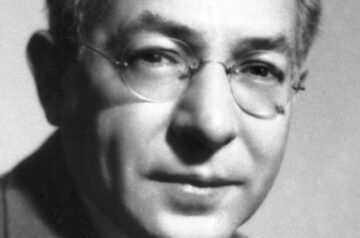

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

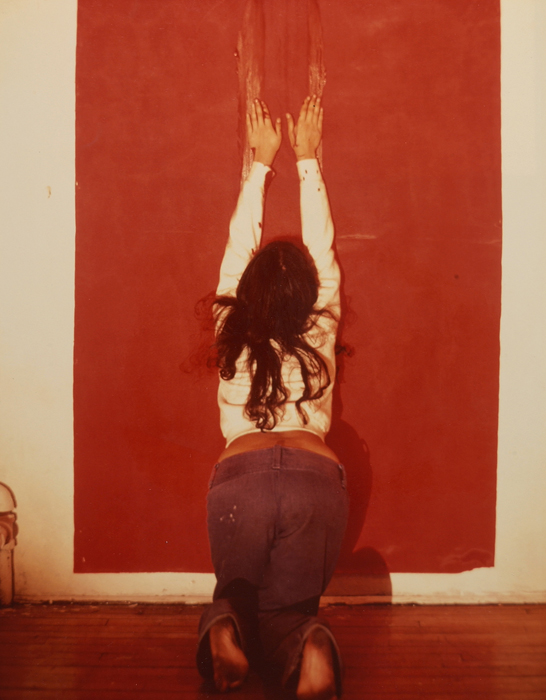

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.