by Jerry Cayford

The Vegetarian Fallacy was so dubbed by philosophy grad students in a well-oiled pub debate back in the 1980s. There is a fundamental conflict—so the argument went—between vegetarians and ecologists. The first principle of ecology—everything is connected to everything else (Barry Commoner’s first law)—is incompatible with the hands-off, “live and let live” ideal implicit in ethical vegetarianism. The ecologists took the match by arguing that, pragmatically, animals either have a symbiotic role in human life or else they compete with us for habitat, and those competitions go badly for the animals. In the long run, a moral stricture against eating animals will not benefit animals.

Now, pub debates are notoriously broad, and this one obviously was. A swirl of issues made appearances, tangential ones like pragmatism versus ethics, and central ones like holism versus atomism. In the end—philosophers being relatively convivial drinkers—all came to agree that pragmatism and ethics must be symbiotic as well, and that the practice of vegetarianism (beyond its ethical stance) could be more holistically approached and defended. Details, though, are fuzzy.

A fancy capitalized title like “Vegetarian Fallacy” may seem a bit grandiose, given the humble origins I just recounted. What justifies a grand title is when the bad thinking in a losing argument is also at work far beyond that one dispute. And that is my main thesis. So, although I will elaborate the two sides, it will be only a little bit. I am more interested in the mischief the Vegetarian Fallacy is perpetrating not in the academy but in wider political and cultural realms. Read more »

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.  The

The  Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

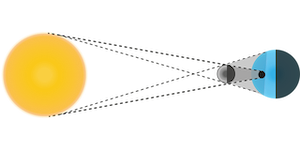

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.  There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.