by Angela Starita

Captains back from Barbados, manor houses, sugar plantations, slavery. This is the economic backdrop of a Jane Austen novel. But New Jersey, central New Jersey, was, it turns out, a locus of this trade too. Or more accurate to say, it was a locus of the fruits of the sugar trade. A website I found written by an amateur historian talks about the huge size of a fortune by a family called Morris all made in the sugar trade. He goes on to talk about enslaved people coming from Barbados who had learned farming there and then in NJ learned iron smithing. In 1804, New Jersey law stated that the children of slaves born after July 4, 1804 would be freed on their 21st birthdays if female, 25th if male. This of course kept slavery largely in place and in fact, NJ was the last northern state to abolish slavery, the result of an amendment to the state constitution in January 1866.

The Morris estate is a short walk east from the site of the North American Phalanx (NAP), a planned community built on the ideas of a French philosopher, Charles Fourier, mentioned in earlier columns. Constructed on a 673-acre site Colts Neck, NJ in 1843, the NAP sought to provide residents with work both meaningful and pleasurable. The land had previously belonged to someone named Joseph Van Mater. One source claims that he was single and aspired to own 100 slaves, but deaths (presumably the slaves’) kept him from reaching his goal. It goes on to say that “in his will he [Van Mater] freed all his slaves and, stories handed down, tell us they wandered up and down Phalanx road for days, lost and forlorn.” The NAP wouldn’t let them stay on the land they’d worked their whole lives. Commentary on the NAP rarely mentions the site’s past or the irony that a community designed to free us of drudgery had, just a few years before its founding, been worked by slaves.

*

I know nothing about the history of slavery in neighboring Howell, the town where I grew up. In my years there, the mid-1970s-’80s–there were two distinct Black neighborhoods. One was about a quarter of a mile from my house; the other along Route 9 near a poor white neighborhood of converted summer bungalows called Freewood Acres, a portmanteau of the two adjacent towns, Freehold and Lakewood. To call these areas neighborhoods might imply a grid of streets with houses, but both were more like family compounds–one piece of land with woods on either side where maybe ten small shacks arranged in no particular order that I could discern without internal streets or walkways separating them. I’d heard classmates refer to one of the two as the Black Village; in my hearing at least, it wasn’t a pejorative but a geographic point of reference. I only knew two Black girls from the neighborhood near me, and we never talked about how our families came to live in Howell. Read more »

There are only four U.S. states where white people are

There are only four U.S. states where white people are

Even after discussing Daniel Chandler’s inspiring

Even after discussing Daniel Chandler’s inspiring

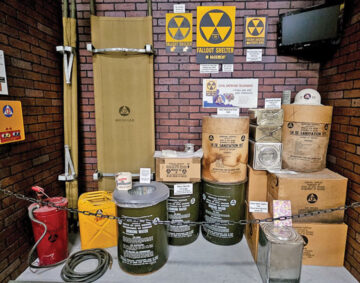

How did the survey come about? FDR had created an Office of Civil Defense in 1941, but it took the USSR’s first atomic bomb test to prompt Truman to reboot it in 1950 as the Federal Civil Defense Administration. In 1958 the FCDA begat Eisenhower’s Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization; in 1961 the OCDMA, moved by Kennedy from the executive into the Defense Department, became the Office of Civil Defense (tradition!), which soon launched its National Fallout Shelter Survey Program. Including those designated earlier, by 1963 the government had identified shelter spaces for 121 million people, and stocked enough of them for 24 million.

How did the survey come about? FDR had created an Office of Civil Defense in 1941, but it took the USSR’s first atomic bomb test to prompt Truman to reboot it in 1950 as the Federal Civil Defense Administration. In 1958 the FCDA begat Eisenhower’s Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization; in 1961 the OCDMA, moved by Kennedy from the executive into the Defense Department, became the Office of Civil Defense (tradition!), which soon launched its National Fallout Shelter Survey Program. Including those designated earlier, by 1963 the government had identified shelter spaces for 121 million people, and stocked enough of them for 24 million.

For a couple of days, some things at 3QD may not work exactly as expected. We will be updating some of the pages at the site in the next few days. We appreciate your patience!

For a couple of days, some things at 3QD may not work exactly as expected. We will be updating some of the pages at the site in the next few days. We appreciate your patience!

.

.