by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Laurence Peterson

Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with. —Richard Rorty

Truth is nothing but a bad excuse for a poor imagination. —Unknown

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s On Bullshit (Princeton University Press, 2005) as a book, his view, in a way almost unknown in philosophy, has generated absolutely no strongly dissenting accounts in the score of years that have elapsed since its publication.

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s On Bullshit (Princeton University Press, 2005) as a book, his view, in a way almost unknown in philosophy, has generated absolutely no strongly dissenting accounts in the score of years that have elapsed since its publication.

As I write these lines, I have before me a Wired piece from June 19th, 2024, “Perplexity Is a Bullshit Machine”, which itself links to another piece, published a mere 11 days earlier in Ethics and Information Technology, called “ChatGPT Is Bullshit”. Both articles pretty much ratify Frankfurt’s view of bullshit in a wholesale manner, which suggests to me that Frankfurt’s original position maintains its utter dominance in discussions of bullshit, and retains a vigorous wider relevance up to the present day. In my mind, there is something unusual, something exaggerated about the bullshit phenomenon that says something unique about the way we all live today. In this piece, I would like to attempt to subject Frankfurt’s view to a more fundamental critique than any I have seen in the last twenty years. Read more »

by Azadeh Amirsadri

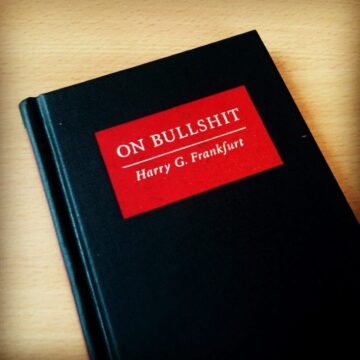

In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the magic of that gold bar of soap.

In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the magic of that gold bar of soap.

In the summer of 1975, when I was 16 years old and a rising junior in high school, I fell in love with a young man who was a college student. We had a standing date every Thursday where he was off from his internship at an architectural firm and didn’t have to attend classes at the university; and me, damn any class that was going to stand in my way of keeping me away from him. Every Wednesday evening, I would take my grandmother’s soap, go in the shower and rub my body with that gold Dial. The next day, I skipped school to hang out with him, first in parks and coffee shops, eventually graduating to stairwells where we would kiss frantically, but faced the danger of getting caught. Then when he finally could afford it, he bought a Citroen Deux-Chevaux, and would pick me up from school where we had the whole city of Tehran to ourselves. We’d go to dark restaurants that were so popular in the 1970’s where you could make out under the cover of semi- darkness, especially after over tipping the doorman. We’d go outside the city and walk around talking about our scorching love and how no one has ever known this type of love, no one ever will and how lucky we were to have created this magical connection.

My Thursdays during the school year were wrapped in the loving perfume of his sweet words and the faint scent of my grandmother’s American soap. Read more »

by Eric J. Weiner

One always has exaggerated ideas about what one doesn’t know. —Albert Camus

From a Deweyan perspective, public education’s central role in a democracy is to provide the conditions for students to learn the skills, knowledge, and habits of mind that are essential for democratic life. For Dewey, democracy is a form of associated living among heterogeneous peoples and therefore requires students to learn how to understand, interrogate, evaluate, and manage conflicts, big and small, democratically. The ability to evaluate, understand, and resolve our conflicts peacefully and respectfully are an important index of democracy’s health and viability. Just as the health of a nation can be measured by how well its children fare, the health of a nation’s democracy can be measured, in part, by how well it teaches its children.

Constrained by constitutional principles of justice, liberty, and rights, educating future generations to be able and willing to live democratically means that schools must stop privileging safe spaces over brave spaces and help students lean into the most difficult and challenging conflicts of the day. Conflicts should not be avoided and our students should not be protected from them. On the contrary, they are a vital pedagogical and curricular resource for developing syncretic knowledge and cultural literacies; an opportunity for dialectical and intersectional thinking; offer a check against coercive and indoctrinating pedagogies from both the left and right; and make the learning experience democratic, meaningful, and transformative.

Mirroring its societal context, schools today at all levels are politicized and polarized to a degree where democratic education is seen by many as a luxury we can no longer afford to practice because of the threat of authoritarianism. They believe that the drift toward some embryonic form of American authoritarianism demands a hard stop when it comes to teaching about issues from different “conservative” heterodox perspectives. These include White Christian Nationalism, MAGA, and other anti-democratic/pro-authoritarian ideologies and their associated ideas, practices, and policies about everything from immigration to abortion. For others, ironically, democratic education represents a threat to American Exceptionalism. They see democratic education as a form of leftist indoctrination and therefore believe it must be policed, disciplined, and restrained. For these folks, American democracy has reached its tipping point in which its excesses have overwhelmed its value as a check against monarchy, communism and totalitarianism. Both sides reject democratic education as a way forward, choosing instead to double-down on the politicization of education in the name of “freedom.” But their conception and practice of freedom is “negative” in that it is driven essentially by fear, avoidance and escape. Politicization of education is a tool wielded by those who fear that their ideas won’t hold up under critique. Read more »

Saw this creature outside my house. I am told it is called Podarcis muralis, or the European wall lizard.

by Nils Peterson

I have finally come to understand that I cannot read everything. There aren’t enough years left. So, what should I read?

The question is complicated by the fact that I have a taste for not very good literature. I like John Buchan despite his racism, anti-Semitism, sexism, and his foolish sense of the supremacy of the English gentleman.

39 Steps, based on his novel, was the first Hitchcock movie I ever saw. In the mid-40’s, I was invited to be for a few days the companion of a boy, a grandson of the old New York aristocracy. He lived with his mother in a great apartment a couple of stories high (the apartment, not the building) near Gramercy Park. One afternoon, his twin sister went with her friend to the ballet. I was envious, but his mother took us to an arty NY movie theater to see what seemed to be thought of as boy’s fare. I was entranced by the film, and, when I got back to my own home, went immediately to the library and got the novel. I’ve read it since at least a half dozen times. It’s quite different from the movie. A great movie. (Not a great, though engaging, book.) I liked somewhat, no, quite a bit, less (most are really dreadful), E. Phillips Oppenheim (though The Great Impersonation is fun) and am glad one can find things like that on the internet.

I’ve liked H. Rider Haggard whose novel She was Carl Jung’s favorite because it portrayed so well his sense of the anima, the female energy he thought we all had a version of. I have managed to save through the years a Classic Comic version. There is also an excellent Jungian analysis of it, Anima as Fate, by the Jungian analyst Cornelia Brunner. She gives a chapter-by-chapter plot summary as she goes through the book if you haven’t the heart for the text. (I bet you’d find it interesting.) And I liked Rafael Sabatini, particularly Scaramouche with its opening sentence, “He was born with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” When I read that as a boy, I thought there could be no finer writing nor richer sense of the nature of the world.

You must understand that the above is not necessarily a list I am proud of, but I cannot, should not, disown it. I change my mind. I’m proud of it. Read more »

by Terese Svoboda

Built in 1958, the father designed the house along the lines of Frank Lloyd Wright, with a flat roof, lots of full-length glass windows, old brick, patios instead of porches, and a sunken garden with a St. Francis birdbath surrounded by ivy beside the entrance. The door had a starburst handle in the middle. Actual prairie abutted the house, as it was situated at the edge of town, population five thousand, not the best place to show off architecture unless there were parties of out-of-towners. The entrance hall where the guests arrived was covered with irregular big pieces of flagstone broken by a wall of amber ripple glass girded by mahogany. The flagstone continued on the other side under a circular wrought iron glass-topped table and chairs and a bar. An expanse of an oatmeal-color-carpeted living room met the flagstone just past the powder room and master bedroom, which was situated as far as possible from the children’s sleeping quarters.

Very soon the sunken garden was sacrificed to the plethora of children. Enclosed, it became a bedroom for whomever was about to escape the house. The occupant had to go through the father’s office, where he lounged behind his desk after hours, usually asleep, farm boots beside the chair. His labors on the land had produced this house meant to keep his wife happy so she would not miss the other end of the state where all things architectural happened.

The rest of the children had to find a place in the basement that was never quite finished, or occupy the TV rec room where ostensibly guests might sleep, if the parties went late. This room was soon converted into a bedroom for more children. It had what is known as a dry sink, an anomaly of a closet, really just a half-closet. The definition is a cabinet with a recessed top where one could put a pitcher of water but this one had a door and a lock that eventually the father’s caregiver used to conceal things she was stealing. The youngest was molested in that room by a friend of the family. Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

With apologies to Charles Dickens, it will be the best of times, it will be the worst of times.

With apologies to Charles Dickens, it will be the best of times, it will be the worst of times.

In his recent book, Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World, philosopher Nick Bostrom, the author of Superintelligence, speculates about human and trans-human lives after AI has developed to a kind of fearsome maturity at some indeterminate point in the future. What do our descendants do when AI can do virtually everything faster, more efficiently, better than they can? What, if anything, will be worth doing is the question underlying much of the book. Will we be become terminally jaded without purpose or will be become, as Bostrom puts it, mere hedonistic “pleasure blobs”?

The book provides a bountiful wealth of details, speculations, and extrapolations on boredom, interestingness, repetitiveness, and activities that might replace and make up for our loss of functional work and meaningful vocations. He mentions activities such as amateur art, music, personal reveries, social interactions, gardening, and the like.

The closest contemporary version of our distant descendants might be very wealthy young retirees or entitled trust fund kids. Still, the latter are not at all the purposeless self-indulgent, bored, unproductive, nihilistic descendants he first sketches. Gradually Bostrom attempts to complexify and significantly brighten this dim characterization of our distant future utilizing a variety of abstract philosophical arguments citing Malthus, Nozick, Thaddeus Metz, and many others. (The conceit is that these lectures are delivered by a professor (essentially Bostrom) to three students who rarely ask questions.) Read more »

by Richard Farr

On a road trip once, navigating a deliberately eccentric route from Houston to El Paso, I was enjoying the emptiness — rocks, ravines, three other vehicles per hour — when I spotted something alien and odd. On a ridge to the northwest two monstrous hard-boiled eggs sat fresh-peeled and gleaming. It might have been a witty installation by Claes Oldenberg. I stood by the car in the brick-oven heat and peered at my paper map.

The ridge was part of the Davis Mountains; the eggs were the U of T’s MacDonald Observatory. I pulled into the parking lot just as a tour group emerged from a purple van. Their bumper sticker said ASTRONOMERS DO IT ALL NIGHT. They looked like extras from a movie about the glory days of the Apollo program. One of the men actually had a buzz cut, a pocket protector, and eyeglasses mended with tape; it might almost have been cosplay, but wasn’t.

One of the resident gazers gave us an al fresco lecture. The astro-tourists didn’t ask him which end of the telescope was which. They asked about precession, and how to collimate the mirror in a large Dobsonian, and how to get the best out of deep-sky subjects with hydrogen-alpha filtering. One of them mentioned the Veil Nebula; others nodded sagely and proffered advice on best practices for capturing the Rosette, the Tarantula, the Horsehead. They discussed how to star-hop from M-this to NGC-that as if comparing routes to Albuquerque. Our guide warmed to them, digging deeper into his expertise, tossing off references to Fraunhofer lines and Cepheid variables.

It was unexpected and strangely exhilarating to find this intense, quirky, intelligent inquiry, naïve inquisitiveness in the noblest sense, in the emptiest reaches of Texas. In universities, in the urban wilderness, you sometimes meet people like this. Just for the jazz of it they’re retranslating Hölderlin’s poetry or trying to prove Goldbach’s conjecture or performing Palestrina on the original instruments. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

As you slide toward retirement age, it becomes clear that you have not accomplished what you had hoped by this point in life and that the meaning of it all is still as unfathomable as it was when you were thirty. You have resigned yourself to the fact that you do not know half the things you thought you knew, but you do know for certain that what you do not know advances by orders of magnitude every day and will continue to do so long after you are dead. The boundaries of human extravagance leap forward light-years by the minute without waiting for you and there is no point in trying to keep up. Might as well spend your remaining time on the planet thumping your fingernail against a string.

*

Hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years ago somewhere in Africa, a village wag became bored with banging an animal hide-covered hollow gourd with his mere hands. So, he attached a stick to the gourd (it could very well have been she; perhaps she wanted to stir men out of their torpor), ran two or three strings of plant fiber from the top of the stick to the base of the gourd, and thumped the strings against the animal hide top, a sound that immediately seized hearts. The villagers couldn’t help dancing. It’s inspiring to know our predecessors were as bored with monotony as we are today and made stuff up as they went along. Even this short history is half fable.

*

This innovation made its way to the New World via the slave trade. Like any entity in a Darwinian universe that gains a foothold in a new geographical location, the immediate response was adaptive radiation. The entity spread widely and became fixed in the population. Mutations ensued: Gourds and fibers were substituted with wood and steel; bridges, strings and frets were added or subtracted; styles multiplied and diverged, fruitfully. One struck the strings with one’s fingernail and thumb, or with finger picks, or with plectrums. These respective cults of the banjo retreated to separate corners of the continent, appearing at square dances, in minstrel shows, on steamboat decks, finally in jazz bands and even concert halls. They would all come to rub elbows again at latter-day banjo camps. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

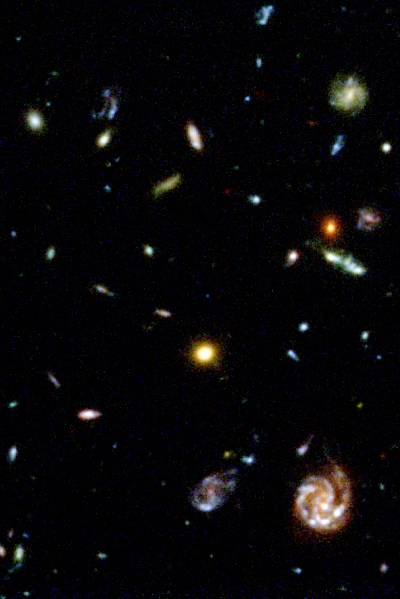

In the shapeless but often suggestive scatter of stars across a dark night sky, humans have picked out patterns and woven countless tales around them, giving the brighter stars names for their place in these stories. The star names we use today can be fascinating but also baffling—which is not surprising, considering that they’ve evolved over centuries in various languages.

Most of the traditional star names known to Western science have Arabic, Greek, or Latin roots. Some of these names have fairly straightforward meanings, although the connections are not always obvious. Orange-red Antares, for example, is named for its resemblance to Mars (the name can be translated as rival of Mars). Regulus means little king; the star has long been associated with royalty, and it’s in the constellation Leo, the lion (king of the beasts). Spica is the brightest star in the constellation Virgo (the maiden); its name is derived from a Latin term for an ear of wheat, because of the constellation’s identification with a Greco-Roman goddess of agriculture. It has been identified with many other female deities over time.

There’s also a star in Virgo named Vindemiatrix, which translates from the Latin as grape gatherer, because in classical times, when it was named, the Sun was in Virgo during the grape harvest. A star in Lyra (the lyre) is named Sulaphat, which is derived from an Arabic word for tortoise. It puzzled me to learn this; the reason is that lyres were often made from tortoise shells. The name of Arcturus, in the constellation Boötes (the herdsman), is derived from a Greek term meaning guardian of the bear, for several possible reasons involving myths about bears. Read more »

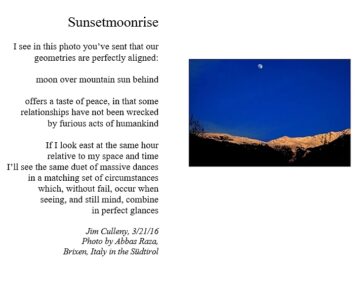

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.

Digital photograph.

by David J. Lobina

So, then, is the American politician Ron DeSantis a fascist? Is former (and maybe next) US President Donald Trump a fascist? What about the Republican Party these two politicians belong to, is it a fascist party? Are some strands within the modern British Conservative party, to move to this side of the world, a case of fascism too? And is fascism also present, to now move out of the English-speaking world, in the current governments of Italy, Hungary, and Russia or the various opposition parties in France and Spain?

These are some of the questions I have alluded to here and there since my post on the use and abuse of the term fascism in current political commentary, the first of a series of on Nationalism and Fascism. It might be a bit Procrustean to claim that all these currents (and undercurrents) encompass fascism, but this is exactly what one finds in the media, especially in the English-speaking world. In fact, there have been further cases of this sort of talk since my opening salvo, including from the very people I had singled out at the time, whilst the reaction the post received, both publicly and privately, was quite interesting in itself – trebles all around for doubling down!

So, to recap post number 1. The word “fascism” comes from the Italian fascismo, and the political phenomenon is also Italian in origin, properly starting in the 1920s. Both the word and the politics were soon adopted in other parts of Europe, and eventually elsewhere in the world, under different conditions and often becoming, naturally enough, slightly different phenomena. Thus, whilst it is customary, and correct, to consider Mussolini’s and Hitler’s regimes as fascist under a certain reading, Fascism and Nazism (in capital letters) were different in rather important respects, and plenty of scholars treat them as distinct ideological and political movements. Renzo De Felice, for instance, an early and quite influential expert in fascism, did not regard Nazism as a species of Fascism at all, and he argued this was even more the case for Franco’s regime in Spain or Salazar’s in Portugal.[i] Read more »

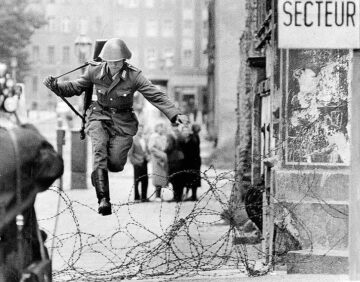

by Mindy Clegg

The Cold War ended somewhere between 1989 and 1991 or if you take the disintegration of Yugoslavia into account, maybe into the 2000s. It is now seen as the end of an era, a closed loop in history. It started with the Communist revolution in 1917 and ended with the end of one-party communist rule in Eastern Europe. The dissolution of the Soviet Union especially signaled the end of the debate about the two supposedly opposing economic systems. The argument goes that communism as practiced in the second world proved unable to keep up with the productive capacity and flexibility of the western capitalist systems, which (many believed) were underpinned by truly democratic norms.

But what if it’s not the struggle between capitalism and communism that was really at the heart of the twentieth century, but was really a more expansive struggle within the world system that developed since the sixteenth century? What if we’re still in the midst of it? I argue that there was a deeper conflict rooted in the debate over who gets to decide how our societies function. This struggle reaches back to the past and shapes our present. We can see this deeper struggle within the communist-capitalist conflict, as that narrative allowed the US and the Soviet Union to double-down on various bad-faith actions with regards to either their own populations or their actions abroad. The fight is between democracy and authoritarianism, the people and the powerful. Democracy clashed with the authoritarian reactionary forces since before the age of revolutions, making the Cold War merely a part of a larger dialectical discourse of the modern world. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Steve Szilagyi

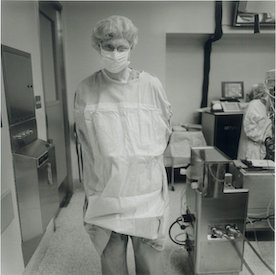

After eight years writing publicity for a cable television network, I was let go. Just in time. I was hankering to get out of Manhattan, go back to my hometown, and marry a girl I knew in high school. Once I’d gotten all that out of the way, I found myself in need of a job. The rust belt city of my birth offered nothing as glamorous as the position I’d left. So I took a job at the local hospital – which happened to be a top-ranked academic medical center. They needed someone to write their employee newspaper. I thought I’d do that humble task for a few years, then retire and lead the literary life. You see, I’d written a novel, and I was pretty sure it was going to be a hit. And it was.

Somehow, the tumblers of fate fell into place and unlocked the doors to an agent, publisher, good reviews, and, finally, interest from Hollywood. In between writing for the hospital, I was doing interviews, book signings, TV, and radio. On my lunch hour, I stuffed coins into a hospital pay phone, calling Los Angeles and London, while producers bid for the right to film my book.

The movie starred an Academy Award-winning Best Actor, and I got a standing ovation at the North American premiere. The money was good, but it didn’t last forever. And I never missed a day at the hospital if I could help it. Week after week, I plugged away at the employee newspaper. My second novel didn’t come so easily, living as I was in a small house with a child.

That was okay. I was being drawn into the world of medicine. An essentially silly man, myself, I was in awe of these serious people. They didn’t know or didn’t care about the book or the movie. I worked hard to prove myself, and eventually became a kind of writer-at-large for the physician leadership. One year I was writing promo copy for Rodney Dangerfield; the next year, I was writing speeches for brain surgeons. Read more »

by Daniel Shotkin

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau prophetically declared that “we badly need someone to teach us the art of learning with difficulty.” Two hundred and fifty years later, Rousseau’s words seem clairvoyant in their relevancy to schooling in the United States. Education has come to the forefront of the array of issues emerging in the post-Covid era. The abandonment of the alphabet soup of standardized tests, student reliance on Chat GPT, and rampant grade inflation all point to a wider problem. And though some politicians see the Ten Commandments as the solution to classroom troubles, universal progress toward a real solution seems far away. Not that some don’t try.

Joe Feldman is not an activist; in fact, until recently, he was simply an attentive principal. Working for over twenty years in education, Feldman compiled stacks of hard data trying to answer one question: why was grading so inconsistent among his colleagues?

Two students enrolled in the same course put in a dramatically different amount of work yet shockingly got the same grade. In two classes of the same course, one got 70% A’s, while another received a much smaller 40%. Their grade essentially depended on the leniency (and frighteningly biases) of their teacher, and not on the contents of their course. This discovery correlates with the wider issue of grade inflation; from 2010 to 2022, the percentage of B and C students in all subjects declined, while the number of A students increased. Feldman relates this data to one idea—that student-teacher relationships have to be based on equity.

This idea is laid out in his latest book—Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms. Feldman believes that for many teachers, equity can be a concept that is far too easily brushed off because “teachers use grading practices that are traditional and end up perpetuating achievement and opportunity gaps.” Read more »

by Barry Goldman

Laws do not interpret themselves. No matter how carefully drafted, the language of a law can never be exhaustive and exclusive. Its boundaries will be imprecise, there will be vagueness and ambiguity, and there will always be a tension between the letter and the spirit. Statutory interpretation inevitably requires reasoned judgment.

Not everyone is happy with this state of affairs. For centuries there has been an effort to squeeze the judgment out of the legal process and reduce it to a rote exercise. In the 17th century John Selden wrote:

Equity is a roguish thing. For Law we have a measure, know what to trust to; Equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower, so is Equity. ‘T is all one as if they should make the standard for the measure we call a “foot” a Chancellor’s foot; what an uncertain measure would this be! One Chancellor has a long foot, another a short foot, a third an indifferent foot. ‘T is the same thing in the Chancellor’s conscience.

Selden has a point. We want the law to be clear, and we want it to be uniformly applied. We don’t want judges (or labor arbitrators) to make rulings simply according to their personal preferences. Legislation is the province of the legislature, not the judiciary. All that is true. But when interpretation is required, what should be the judge’s guide? Read more »