by Michael Liss

But they shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees, and no one shall make them afraid…. (Micah 4-4)

Ah, those figs and vines. George Washington liked this sentiment so much that he used it or a variant at least 50 times in his correspondence. It meant going home to Mount Vernon and staying home. It meant disengagement from whatever activities he had committed to on behalf of others. It meant emulating Cincinnatus, the Roman General who, as legend would have it, was living modestly in retirement on his four-acre farm outside of Rome until the Senate called him back to deal with a crisis and invested him with a dictator’s power. Cincinnatus went on to defeat the invading Aequians, and just 15 days after assuming the dictatorship, he resigned and returned to his plow.

Finally, it meant something immensely important to Washington himself, a man who did not lack self-esteem. Retiring to his figs and vines was a seminal display of republican virtue, an ineradicable example to all who would follow him in leadership that one must act with integrity, that power is granted by the people “in trust” and belongs only to the grantor, not the grantee. Power must be returned at the appropriate moment. Washington understood the conditions of that grant, its essentialness to the American experiment, and acted upon it.

We mythologize our great men well beyond the reality of their lives and accomplishments, but that Washington did this not just once, in resigning his commission, but also a second time, in refusing to run for a third Presidential term, seems almost superhuman. George III thought so: when told by the American artist Benjamin West that his long-time adversary was going to resign, the King said, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

The “Greatest Man In The World” is an impressive title. Still, there’s a strange disconnect in trying to animate this titanic figure, the Washington of monuments and marble statues and Mount Rushmore. He was nothing at all like the bouncing, voluble wrecking ball that was TR, or Jefferson’s suave, violin-playing political poet, or Lincoln’s melancholic, introspective grappler of existential questions of life or death, freedom or slavery. Washington’s eloquence was certainly not in words—instead it was in his capacity to endure and to lead.

Mythmaking requires a considerable amount of effort, along with a dose of non-mythical actual accomplishments. Washington managed both. He was very conscious of the image he presented to the world. His personal demeanor reflected this—decorum and deportment were central to defining himself to the world. When he was just 14, he wrote out a copy of the “110 Rules of Civility” in his schoolbook, and they remained a guide for the rest of his life.

Who was he, really? Complex, as all our secular heroes are. You can try to look for clues, but at some point you have to say a man is the sum of his visible parts, regardless of what drives him. Washington is enormously important to the way we Americans perceive ourselves—our politics and our law are increasingly referential towhat the Founders did or did not do or say. With the semiquincentennial coming up, even more attention will be paid to Franklin, Jefferson, Adams, Hamilton, and Washington.

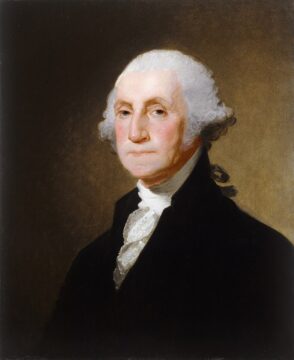

In the public eye, there are probably two dominant Washington images—the stalwart 44-year-old General of Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington Crossing The Delaware” at the top, and the aging, diminished 66-year-old President Washington you see across on the right in Gilbert Stuart’s 1796 “Athenaeum Portrait.” The Athenaeum was an unfinished painting that was used as the model for the engraving on the one-dollar bill—and for Stuart’s cash-cow, as he made and sold roughly 130 copies at $100 each to patriotic families of means.

Stuart also painted the full-length 1796 “Lansdowne” portrait of Washington in the National Portrait Gallery’s Hall of Presidents, and it is resolutely, even heroically, Presidential. Look at the arm stretched out like a famous baritone after he’s completed his aria; look at all the symbols of power and ancient virtue. The story is that, when the British captured Washington D.C. during the War of 1812 and burned down the White House, Dolly Madison rescued the painting at the last minute by having it cut out of its frame and rolled up.

It’s incredibly unkind of me, but there’s something missing in all three of these. The problem with the Leutze painting is that you really don’t see Washington’s features—the figure is heroic, but in profile and at a distance. The problem with the Lansdowne is that it is too posed, too mannered. It exposes Washington’s ego but doesn’t tell you how he merited it. The problem with the Athenaeum Portrait is, to my eye, as much a function of its static nature as it is of the depravations of age. We ought to be able to see our heroes being, or at least looking, heroic.

Stuart disappoints me here, especially since he’s quite capable of delivering works of immense appeal—his 1782 “The Skater” created a sensation in London and is absolutely one of my favorite paintings. It’s great, isn’t it? The stance, the expression on his subject’s face. Look at what youth and vigor can do, both in the subject and the artist.

How do we put younger, more energetic flesh on old bones? We have to look for it.

On Memorial Day weekend, I went down to Lower Manhattan, found Fraunces Tavern, where, on December 4, 1783, the 51-year-old Washington bade a teary and apparently boozy farewell to his officers, and Federal Hall, where, on April 30, 1789, he was sworn in as our first President. I stopped at St. Paul’s Church, where he prayed after assuming the Presidency. Steps away, Trinity Church, the sad final resting place of Alexander Hamilton and his beloved Eliza (while we were there, a large contingent of star-struck teenagers came by to look at the eternal romance). A few weeks later, on the Fourth of July, I saw, at the New York Historical Society, the Bible used for Washington’s swearing-in. It should not surprise that it is a very weighty tome.

I don’t know that any of that got me any closer to the Father of Our Country. He was an 18th C entury man doing things that few do now. He left the comforts of Mount Vernon and family and gave more than eight years of his life to free his country, fighting for liberty while living the contradiction of keeping hundreds in bondage. He was someone used to being obeyed, yet willingly shared in the deprivations his often rag-tag army had to endure, exposing himself over and over in battle to lead them. Finally, he was an aristocrat of impeccable manners and immense reserve who kept nearly everyone at arm’s-length, yet someone who managed to inspire an unbreakable loyalty in more mortal men. The rituals I saw depicted were just that—rituals, symbolically important, but not relatable. The man at the center of them…still remote, unapproachable.

Two things helped in bridging the gap.

The first was a terrific 1780 painting by Charles Willson Peale, an imagining of Washington after the Battle of Trenton. It’s what I would have hoped for from Stuart. First, you can’t take your eyes off Washington’s sheer size—it radiates power. Second, look at how he’s posed, the lean to the side, one hand on hip, the bent left knee, the angle of his body. This is a self-confident man, someone you can follow into battle and know he will not falter.

Second, a story that may have contributed to his decision to return to public service after earlier resigning his commission. After Fraunces Tavern, after the British had formally surrendered and left New York, Washington went to Annapolis. There, on December 23, 1783, in an elaborate ceremony choreographed by Thomas Jefferson, he formally surrendered his commission to the Continental Congress. He took his leave and made it home to Mount Vernon in time to enjoy Christmas.

He was home, but home needed some sprucing up. He set about creating order on a plantation that had been given very little attention since he had left eight and a half years before. As Mount Vernon was nearly 12 square miles, it demanded a great deal of effort to restore.

For a few months, there were more than enough figs and vines (and crops, distilleries, and smokehouses) to tend to. But, after a while, this man of action itched for more. Washington had two priorities—the advancement of the nation he helped birth, and the advancement of the personal Washington family fortunes.

If the linkage of these two seems a bit unfair and ungrateful, it’s not intended that way. We are not now, nor have we ever been a nation of altruists. Washington saw his own fortunes tied to that of the country itself. He realized that the United States didn’t yet have much of an identity as a country and was not ready to be governed as one. The Articles of Confederation agreed to by the Continental Congress in 1777 were loose, by design, as each former colony hung tightly to its sovereignty. America lacked the homogeneity of many European countries; it was a mishmash of different ethnic groups, different languages, different nationalities, different religions, and different races. It lacked a common history and even a common identity.

The Americans had won their independence, and the Treaty of Paris had granted them immense tracts of land (although remote and populated by Indian tribes who had the temerity to be there first), but they lacked a mechanism to govern or even organize these new assets. Finally, the British left—but not completely, as they ignored portions of the Treaty and retained forts in what was the Northwest Territories. The new nation was not exactly surrounded by friends.

Washington saw that, without a national goal beyond mere survival and the tending to personal economic interests, all that had been won could be lost in just a generation. Like many Americans, he looked West (“West” being not California, but simply past the Allegheny Plateau and into the Ohio Valley). These areas needed to be surveyed, settled, and improved, integrated into a political structure, and connected to the older colonies with access to the Atlantic.

His solution was the Potomac River (which ran through his own plantation). It would be the great artery for commerce from the seaboard States to the fertile interior. Washington himself owned a great deal of land west of Mount Vernon, including virgin forest, which he had learned about during his service during the French and Indian War and later bought from afar. If he could show that the Potomac was a viable concourse, then his vision of a cohesive American empire, stretching hundreds of miles into the interior and bound together by mutual self-interest, was attainable.

Of course, Washington had to prove it. So, on September 1, 1784, this wealthy national hero packed up a few things, and, with a small party, left his gracious estate and set out through the backwoods, through ravines, over mountains, on rutted trails or no trails, on horseback, on foot, in canoes, past sometimes (justifiably) hostile Native Americans and snakes (of both the reptile and human variety), and through all sorts of tricks that unforgiving Nature can play. The goal: to find a path to connect the Potomac to the West.

On his trip, he saw confirmation of his concerns. In the east, the fertile bottom soil that had made Virginia planters rich was now denuded of nutrients by the harsh effects of tobacco cultivation. Washington himself had observed this at Mount Vernon, and had switched from tobacco to grain cash crops by 1765, but others had not been so farsighted. In the need for new land to replace the old, forests had been cleared and no longer had the root system to hold the earth in heavy rains, accelerating erosion and diminishing further the usefulness of a considerable amount of farmland. The deeper Washington went into the wilderness, the more it became clear that his new country needed the West, needed the animals, the timber, the land. Without it, there would never be an American Empire, just a loose confederation of States arguing over narrow economic issues and limited resources.

Washington traveled 680 miles through absurdly unforgiving terrain, visiting some of his own lands (and, in places, arguing with the squatters who stayed there and refused to pay rents), drawing maps, keeping a diary of the smallest details, and always planning for a route for the Potomac. For 34 days, sometimes with a small party, sometimes perhaps with just a servant or alone, he scrambled up and down hillsides and mountains, into ravines, over “roads” that were barely ruts, and ruts that disappeared to leave him no option other than bushwhacking.

He and his party kept going, occasionally getting lost and having to backtrack. They stopped at houses in remote areas along the way, knocked on doors, and were invited in for a meal or to stay a night. Some of the places were essentially hovels, occupied by farmers barely scratching out a sustenance existence. Once the meal was just boiled corn. Try to visualize being in a rough hut in the remotest of frontier areas, living a life of mostly isolation, when a tall, robust, elegant man dismounts off a fine horse and introduces himself as General Washington.

There is a moment, later on in the trek, where he sent some of his party ahead, along with most of the remaining supplies (including the tents). He then rode southeast through the Alleghenies and crossed Briery Mountain in what is now West Virginia. The ride became ever more punishing, and there came a point where the path ended in an isolated glade, without a house in sight. It began to pour, and the great man, who had conquered the British, and could himself have been King, now without even a tent, huddled on the ground under his cloak, literally in the middle of nowhere, getting soaked.

Washington survived this, of course, and there is a happy ending. Near the end of the trip, he ended up getting lost twice and finally taking shelter with Captain John Ashby, who had served under him in the French and Indian War. He ate breakfast by candlelight the following morning, then allowed himself to be guided by Ashby on impossibly confusing roads until he made the final 30 miles and found himself home, at Mount Vernon.

He was a man on fire. Through the mud, the insects, the impassable and the unavoidable, the physical and mental challenges, he’d found just what he was looking for—a rich land to be conquered, a river he could wrestle into obedience, and a fractured nation he could help knit into one to make it all happen. While it would be years before the Constitutional Convention and the Washington Presidency, the land and the Potomac were right there.

All they needed was the Washington touch, and he was ready for the challenge. The figs and vines would wait.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.