by Monte Davis

If you know more about fallout shelters than a dark TV comedy based on a video game, you probably know that people are still finding relics in basements and storerooms of old schools, hospitals, and factories: olive-drab drums of water, cartons of high-nutrition crackers, first-aid and sanitary supplies, even bicycle-driven fans to bring in filtered air through a vinyl hose. Boomers have a few snapshot memories, their children and grandchildren just the memes: “duck and cover” exercises, CONELRAD emergency warnings (their loud hum surviving in weather warning and AMBER alerts), and the yellow-and-black trefoil signs.

For me, the snapshots are frames in a private documentary: Nine Hot Weeks, with Misgivings. In 1967, I spent the summer after my first year of college in a thousand or so basements, surveying potential sites for those shelters in El Barrio, aka East Harlem, Manhattan, New York City. Two-man teams were dispatched in pairs with computer printouts listing every building in our assigned area, as other teams covered other neighborhoods. We also carried a letter of introduction in several languages, which asked building owners, superintendents, and ground-floor businesses to cooperate. Because the Big Apple was well connected, the letter was machine-signed by President Johnson as well as Mayor Lindsay. Because the Army was well connected — and 1967 was yet another long, hot urban summer — the NYPD supplied a patrol officer to accompany us and radiate yes, please cooperate vibes at the front door. (That chickenshit assignment must have gone to the least popular rookies in the precinct.) But we appreciated their presence, as neither I nor my partner Vytautas Jankauskas – an immigrants’ son a few years from Kaunas, Lithuania, with silver-blond Baltic Targaryen hair – could pass for a homie.

How did the survey come about? FDR had created an Office of Civil Defense in 1941, but it took the USSR’s first atomic bomb test to prompt Truman to reboot it in 1950 as the Federal Civil Defense Administration. In 1958 the FCDA begat Eisenhower’s Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization; in 1961 the OCDMA, moved by Kennedy from the executive into the Defense Department, became the Office of Civil Defense (tradition!), which soon launched its National Fallout Shelter Survey Program. Including those designated earlier, by 1963 the government had identified shelter spaces for 121 million people, and stocked enough of them for 24 million.

How did the survey come about? FDR had created an Office of Civil Defense in 1941, but it took the USSR’s first atomic bomb test to prompt Truman to reboot it in 1950 as the Federal Civil Defense Administration. In 1958 the FCDA begat Eisenhower’s Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization; in 1961 the OCDMA, moved by Kennedy from the executive into the Defense Department, became the Office of Civil Defense (tradition!), which soon launched its National Fallout Shelter Survey Program. Including those designated earlier, by 1963 the government had identified shelter spaces for 121 million people, and stocked enough of them for 24 million.

Congress had never shown interest in building shelters from the ground down on such a scale, so OCD (working through the Army Corps of Engineers) kept the numbers climbing by engaging local architectural and engineering firms to assess existing buildings for space that could be adapted at relatively low cost. For that stage, these contractors sensibly hired college students and other temps who could walk and carry clipboards at the same time.

And so we and the Officer Friendly of the week went door to door on East 96th Street from Central Park to the East River, then moved one block north and went from river to park, stitching back and forth all the way to 116th St. We performed harmlessness at every front door, and went down into basement after basement. We measured for a sketch plan, and noted amenities for a post-apocalyptic stay of two weeks or more: adequate depth below grade, a window for controlled ventilation (but not too many windows), additional water potentially available from standpipes and other plumbing, and so on.

And so we and the Officer Friendly of the week went door to door on East 96th Street from Central Park to the East River, then moved one block north and went from river to park, stitching back and forth all the way to 116th St. We performed harmlessness at every front door, and went down into basement after basement. We measured for a sketch plan, and noted amenities for a post-apocalyptic stay of two weeks or more: adequate depth below grade, a window for controlled ventilation (but not too many windows), additional water potentially available from standpipes and other plumbing, and so on.

We saw lovingly finished basements to inspire any suburban renovator, some of them legal apartments and some not; dirt-floored basements with rat traps, where we wore rubber bands around our cuffs and sprayed flea repellent from our knees down; basements with santeria shrines and cockfighting rings. If we heard too much loud barking from the stairs, we did not evaluate the potential for kennel-to-shelter conversion.

We saw the multiple basement levels of public schools, high-rise housing projects, factories, and the vast NY state hospital complex on Ward’s Island. In many of those we just confirmed shelters designated and stocked years before. For others, the city supplied plans that we annotated – otherwise we’d have been measuring for weeks. On rainy days, we compiled our notes back at the engineering office, and completed lengthy forms designed for use from Maine to Hawaii:

Artesian wells (number) ___ Flow rate (gpm) ___

Waste system: septic tank ___ leach field ___ Sewer (municipal)___Sewer (private)___

“Can we just mark these N/A and skip them?”

“Nah,” our project manager said, “put a zero or write ‘none’ in each space. It’s the Army.” Not even the Big Apple was connected enough to abbreviate the filling-out of forms.

Most of the buildings we surveyed were four-to-six-story, timber-and-brick tenements and unglamorous brownstones built from 1890 to 1920. Of course, if the OCD were to choose them, the basements would become fallout shelters, not blast shelters. And if (as seemed likely) New York City received multiple large airbursts, they would be annihilated or their fragments blasted down into their basements, as one day fire and gravity would do to towers far downtown..

We prided ourselves, as teenagers will, on expecting the worst, and kept private our grim humor about a broad, radioactive new Hudson/East River estuary. We took home $75 a week, and took our project manager for an oblivious adult, solidly with the program. Now I believe that he wondered, too, and that doubts extended all the way up the line to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and to LBJ.

We prided ourselves, as teenagers will, on expecting the worst, and kept private our grim humor about a broad, radioactive new Hudson/East River estuary. We took home $75 a week, and took our project manager for an oblivious adult, solidly with the program. Now I believe that he wondered, too, and that doubts extended all the way up the line to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and to LBJ.

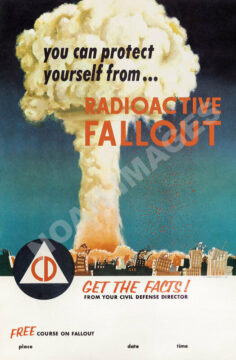

It must have. They knew better than we did that civil defense early in the nuclear age had still traded on reminiscence of Londoners patiently sheltering in Tube stations during the Blitz. Its pamphlets, posters, and planning guides for local governments and civic organizations were earnest but relentlessly upbeat — “keep calm and carry on” with an American accent. Why not? The threat was still bombs from aircraft: the USSR’s subsonic bombers on long, long flights over the Arctic, exposed for long hours to radar detection and US Air Force interception, with hours of warning for their targets. Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe depicted war rooms with huge map screens, small bomber icons advancing very slowly as the statesmen and generals debated.

But by 1964, when those movies came out, that was already obsolete: the US had about 400 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and the USSR about 150, the numbers growing fast. They were ready to arc above the atmosphere twenty times faster than sound, arriving within half an hour of launch. Instead of 1950 atomic bombs rated in tens of kilotons, they carried thermonuclear (“H-bomb”) warheads that could be hundreds of times more powerful. The bombers were assigned a follow-up role. Much more destruction, much more fallout, with much less warning; calmly or not, the survey carried on.

I grumbled between basements that these changes made urban civil defense For Display Purposes Only. Vytautas asked where I’d gathered such details — the kind that didn’t circulate in eastern Europe. I told him how rockets had captivated me through Disney TV broadcasts about space in the mid-1950s. One had featured square-jawed “Dr. Space” Wernher von Braun, taking time off from leadership in the development of our ICBMs. Later I’d looked for every book about space I could find, and inhaled mass quantities of science fiction (nuclear war and aftermath a popular theme). My father worked for an airline, and started bringing home Aviation Week for me when it added & Space Technology to its title. I flipped past the boring civil aviation that paid our bills, briefly admired the sleek military jets, and dove into the Right Stuff — coverage of NASA’s space plans and the ICBMs it adapted to launch US astronauts, from their first sub-orbital flight through the Mercury and Gemini programs.

By 1967, I was less of a technology fanboy and more willing to hear what the summer job was telling me – and it wasn’t about megatons, or roentgens of exposure. I lived three miles south of the survey area. Given an improbably limited “nuclear exchange,” I might occupy one of the pieds-sous-terre we surveyed. Did I believe that I, my family, my neighbors might find it at sudden need? As the weeks went by, I found myself thinking entirely about the “social technology” of getting people into the shelters, on much shorter notice than anyone had foreseen in 1950.

Imagine a small town with shelters under the high school, municipal building, and widget factory. It was plausible that everyone would know where the shelters were. It was plausible that with the right location and the right winds, everyone could be in them before the arrival of the earliest, most lethal fallout from targets upwind.

But by the late 1960s, about 70% of the US population was urban. The question was not really whether our survey would lead to shelter space for millions in New York City. I wondered Who’s preparing millions to know at all times where the nearest shelter is and get to it promptly? Who would match shelter seekers to shelter capacity block by block? Where are the frequent, compulsory drills for all? Because this makes no sense without them.

***

The summer job ended. I worked for the same company the next two summers, at the highway construction projects that were its standard fare. I don’t know if its role in the fallout shelter survey ever led to any actual design or construction work, but I do know that only a very few of the small apartment buildings we surveyed were ultimately selected, let alone stocked. By 1976, when the new Federal Emergency Management Agency absorbed the Office of Civil Defense, the public shelter program had effectively ended. And I was becoming aware of the comic twist at the end of Nine Hot Weeks: In fact, long before that summer, civil defense planners had been thinking about frequent, compulsory drills for all — and had attempted to lay the groundwork while I was still watching Disney. That history had escaped me, even though some of it happened just a short walk from my home.

Go back to 1954, when the Federal Civil Defense Agency staged its first annual “Operation Alert” in major cities across the country. Newspapers, newsreels, and early TV covered volunteers filing calmly into shelters. Local authorities tested their sirens and communication plans. President Eisenhower visited an evacuation site outside Washington, D.C. The agency hoped these events would lead to acceptance of regular community drills.

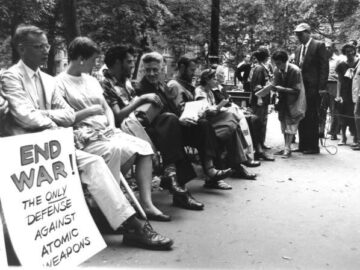

New York state passed a law making it a misdemeanor with a $500 fine not to “take cover” during the fifteen minutes of subsequent Operation Alerts. That rubbed anti-Cold War activists the wrong way: when the sirens sounded on June 15, 1955, 27 protestors issued their statement to reporters and settled on benches in lower Manhattan’s City Hall Park. “We will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide… there is no defense in atomic warfare. We know this drill to be a military act in a cold war to instill fear, to prepare the collective mind for war. We refuse to cooperate.”

New York state passed a law making it a misdemeanor with a $500 fine not to “take cover” during the fifteen minutes of subsequent Operation Alerts. That rubbed anti-Cold War activists the wrong way: when the sirens sounded on June 15, 1955, 27 protestors issued their statement to reporters and settled on benches in lower Manhattan’s City Hall Park. “We will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide… there is no defense in atomic warfare. We know this drill to be a military act in a cold war to instill fear, to prepare the collective mind for war. We refuse to cooperate.”

They were arrested but given suspended sentences. Similar protests followed every year, growing slowly but steadily to a peak in 1961, when more than 2000 protested in New York City, with many more in other cities and on college campuses. Operation Alert for 1962 was canceled, and there would be no more. Still less would there be any realistic preparation for getting city dwellers into public fallout shelters by the millions, with little warning, under extreme stress. Had senior officials, seeing the backlash to a once-a-year symbolic event, worried that real, frequent drills for millions might make them balk? Even make them question the premises of the arms race and nuclear grand strategy?

So as of summer 1967 the public shelter program had already been moribund, a shadow play, survival kabuki. But what about home fallout shelters? They loom at least as large in Internet memory, although their numbers never approached those in OCD’s files. Construction plans for family shelters had been offered all along for farms and other isolated homes, but they enjoyed a brief vogue in growing suburbia, especially after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. There were ant-vs-grasshopper debates: should you shoot your improvident neighbors who want in at the last moment? I had known about home shelters in real time, because my Uncle Chuck added a cinderblock room to the concrete basement of his home in Connecticut. (Today’s preppers, with fewer radiation meters but more guns, are still at it.)

So as of summer 1967 the public shelter program had already been moribund, a shadow play, survival kabuki. But what about home fallout shelters? They loom at least as large in Internet memory, although their numbers never approached those in OCD’s files. Construction plans for family shelters had been offered all along for farms and other isolated homes, but they enjoyed a brief vogue in growing suburbia, especially after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. There were ant-vs-grasshopper debates: should you shoot your improvident neighbors who want in at the last moment? I had known about home shelters in real time, because my Uncle Chuck added a cinderblock room to the concrete basement of his home in Connecticut. (Today’s preppers, with fewer radiation meters but more guns, are still at it.)

Chuck’s do-it-yourself shelter, like many others, remained a bare shell with no furnishings or supplies.

But he also had a cool slot-car racing track in the basement, where he, my brother, and I would perform Le Mans. And one day, when the hyper-elastic Superball was the latest toy craze, the three of us took one to the shelter doorway to count bounces: lots! Soon we were all inside, each trying to throw it harder, dodging frantically as it ricocheted again and again. It was exhilarating in a crazy way. We’d invented a new game – we called it “evilball” — with no rules except don’t get hit. It was going to sweep the nation!

OK, it didn’t catch on. But someone should find the old FEMA mainframe tapes and transfer the data to new media while there’s time. We need to be able to find those potential community evilball courts all across America, just in case peace breaks out.

OK, it didn’t catch on. But someone should find the old FEMA mainframe tapes and transfer the data to new media while there’s time. We need to be able to find those potential community evilball courts all across America, just in case peace breaks out.