by Daniel Shotkin

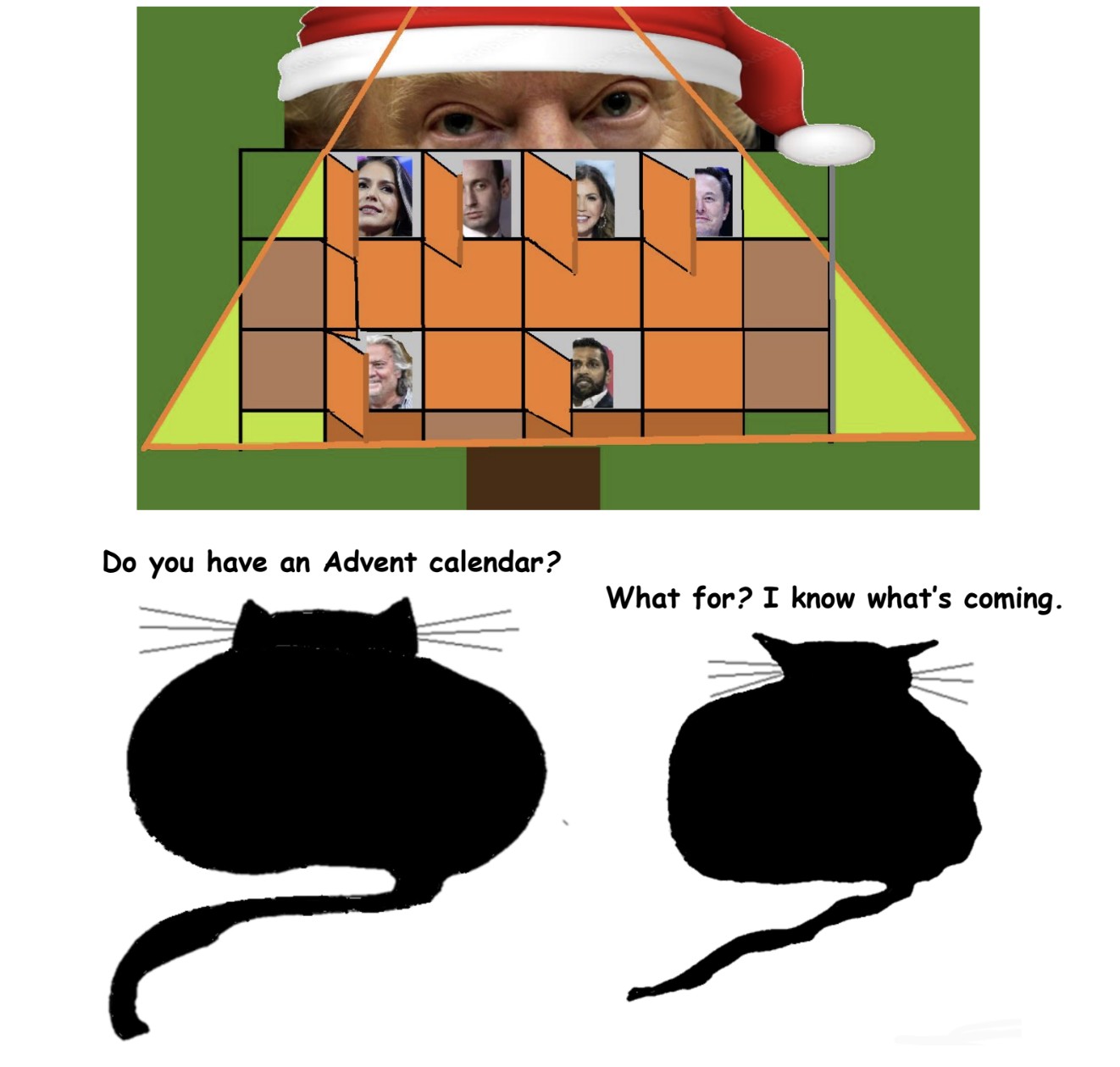

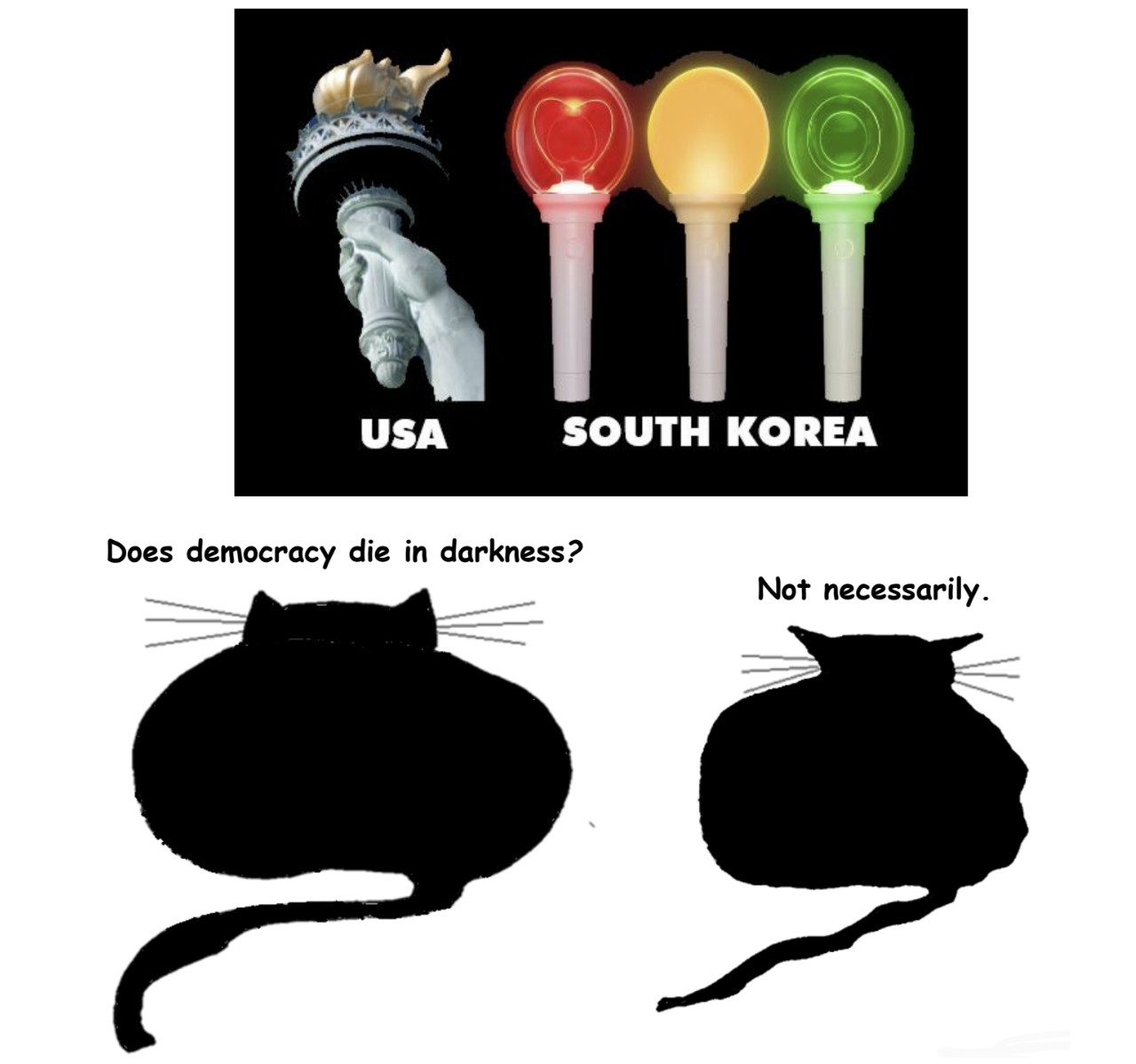

This week, electors from across the country will cast their votes for the next president of the United States. Only now, more than a month after Election Day, will Uncle Sam officially wave goodbye to election season. That seasonal bout of incessant campaign mail and debate fever has found its way off the front pages, replaced by a national rumination over one question: How did we get here?

The overarching answer is that it depends on who you ask. The self-assured economist will tell you that Donald Trump’s election is simply the result of widespread dissatisfaction with inflation—“it’s the economy, stupid.” The zealous Middle East correspondent will point to Kamala Harris’ support of Israel’s actions in Gaza. The MAGA Evangelical will tell you Trump’s win was the direct result of divine intervention. As a poll worker, I have a slightly different take on the election. Instead of focusing on the results, I think we can learn more about the state of America in 2024 from Election Day itself.

To preface, I am not the most typical poll worker. As a high school senior, I signed up to work the polls through a program my school offered with the local town. Eight hours of light work with my friends for $200 was a great deal, especially since we would skip school. But the gravity of this particular gig hit full force during the mandatory four-hour training in our cafeteria—our instructor informed us that “our nation and democracy depend on you.” Quite a lot to ask of forty-odd chattering high school students.

By midday on November 5th, I walked to my assigned polling station unsure of what to expect. I had heard stories of election workers being threatened in battleground states, though I was skeptical of that happening in suburban New Jersey. Our instructor had also warned us to expect “challengers”—party officials inspecting voting procedure—watching our every move. After months of end-all, be-all election coverage, the only thing I felt sure of was that this election, more than any other, would be exceptional. My suspicions were confirmed as the polling station came into view. Read more »

It sounds like a parlor trick or gimmick, to walk 2,024 miles in 2024—trivial but harmless. It’s not like hiking the Appalachian or Pacific Crest Trail or climbing the highest peak on each continent, or running a marathon. But it is similar to a marathon in that the number involved is an arbitrary product of history that can somehow be useful for guiding a person’s efforts.

It sounds like a parlor trick or gimmick, to walk 2,024 miles in 2024—trivial but harmless. It’s not like hiking the Appalachian or Pacific Crest Trail or climbing the highest peak on each continent, or running a marathon. But it is similar to a marathon in that the number involved is an arbitrary product of history that can somehow be useful for guiding a person’s efforts.

Lorraine O’Grady. Art Is … , Float in the African-American Day Parade, Harlem, September 1983.

Lorraine O’Grady. Art Is … , Float in the African-American Day Parade, Harlem, September 1983.

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

The sleet falls so incessantly this Sunday that the sky turned a dull gray and we don’t want to go anywhere, my child, his friend and me. We didn’t go to the theater or to the Brazilian Roda de Feijoada and we didn’t even bake cookies at the neighbors’ place, but instead are playing cars on the floor and cooking soup and painting the table blue when the news arrives.

The sleet falls so incessantly this Sunday that the sky turned a dull gray and we don’t want to go anywhere, my child, his friend and me. We didn’t go to the theater or to the Brazilian Roda de Feijoada and we didn’t even bake cookies at the neighbors’ place, but instead are playing cars on the floor and cooking soup and painting the table blue when the news arrives.