by David J. Lobina

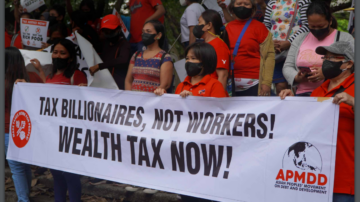

And by ‘them’, I mean, of course, the rich!

I think it is fair to say that such a rallying cry has always resonated with certain people, and perhaps even more so now in the US, with a forthcoming Trump 2 administration seemingly to be filled with billionaires. And I’m sure there is a perfectly reasonable argument in favour of stripping rich people of most of their wealth and assets in one way or another, Marxist or otherwise. A Marxist argument, you say? Is there such a thing?[i]

One such argument would have to say something about the distribution of income in society, either under some form of socialism – to all according to their work – or under some form of communism – to all according to their needs – as Marx argued in the Critique of the Gotha Programme (roughly, of course…); but, in any case, there would be little justification for anyone to be very rich under either society.[ii]

A more interesting argument, which I borrow from one Robert Paul Wolff (link below), has it that in modern capitalism there is a divorce between the legal ownership of large corporations and the de facto day-to-day running of the business. That is, in joint-stock limited liability companies, ownership is widely dispersed in the form of shares of stock, and as a result the managers and directors that run the company operate in a state of relative isolation, with the further result, and this is key, that the Board of Directors (and the like) are rather free to set what dividends and compensation are due. And this in turn results

in a regular, systematic, unquestioned process of theft, [as] a portion of the profits is directed away from the shareholders who are the owners of the corporation and into the pockets of the managers, who are paid vastly more than the going rate for managerial labor [sic].

Or to quote one of the greatest lines in political philosophy:

The simple fact remains that capitalism is a system of economic organization that regularly, quietly, unremarkably transfers a portion of the annual collective social product into the hands of a small segment of the society who have come to own the means of production. As each year goes by, the owners of capital expand their ownership and thereby reinforce their control of the workers whose labor [sic] creates what they take as profit.

Exploitation, in other words, though in modern capitalism such exploitation is relative, by which I mean, following an influential paper, that the modern accumulation process tends to obliterate social distinctions among workers, thereby producing an internal labour segmentation process – a fragmented workforce, that is – and with it unequal rates of exploitation but higher profits for the capitalist.

Or as Lenin had it, as cited in the mentioned paper, there is an aristocracy of labour at play here, and even though all types of labour are exploited vis-à-vis the capitalists, some workers (say, managers) are in turn exploiters vis-à-vis other workers (say, manual workers). The modern corporation as a hierarchically ordered system of authority relations, then, where the capitalists bargain separately with each group of workers, to the detriment of everyone except the capitalists.

In socialism, on the other hand, capital is to be collectively and social owned, and the rationale of the whole system would be to accrue to the benefit of all, and not merely for the legal owners of capital, and thus hopefully doing away with the huge income pyramid disparity between managers and employees – and do away, by extension, with billionaires such as Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, though I should point out that they are the exception rather than the rule in the picture I have just painted (that is, they are both directors and owners, which is not the usual case). In such terms, socialism would not be an attempt, solely, to minimise inequality; the aim would not be to reform or control capitalism, but to replace it.

As for the otherwise argument, I’m pretty sure one can put together a line of reasoning to the effect that the rich wield far too much power within a capitalist society, that this is to the detriment of democracy, and that this ought to be rectified, possibly through taxation.[iii]

But I digress, for my point in this post was meant to be a linguistic one!

Consider the meaning and etymology of the word “expropriate”, the word I used in the title. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the first usage dates back to the 17th century with the meaning of ‘to dispossess (a person) of ownership, to deprive of ownership’, though in modern usage it chiefly refers to depriving of property for the public use, and usually with the provision of some compensation to the expropriated. The word comes from the Latin ‘expropriare’, which itself derived from ‘proprius’ (one’s own), though ‘proprius’ is of Classical Latin origin and ‘expropriare’ dates back to Medieval Latin instead (property rights as we know them today are a product of European modern history).

In fact, the English word “property” is traceable to the 14th century with the meaning of ‘a thing belonging to a person (or to a group)’, though the more common and current meaning today is that of ‘privately owned possessions’, as recorded in the OED, and thus not part of the commons. The word is a borrowing from French ‘properté’, whilst the English ‘proper’, with the connotation of ‘that which is one’s own’, is partly a borrowing from French, and partly derives from the Latin ‘proprius’. The etymology of ‘proprius’, for its part, may be related to ‘privus’ (separate, single), and thus perhaps connected to ‘privare’ (to deprive).

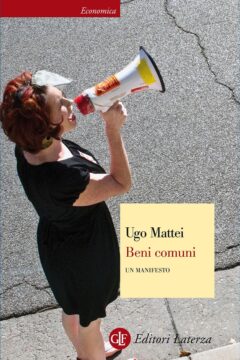

Despite this, in common discourse to expropriate is something that the state or a government does, usually against an individual or a company and for the general use of the public. It is not something that is done against the public. But surely this is a linguistic sleight of hand! One Ugo Mattei clearly thinks so.

In his Italian book, Beni Comuni (the common goods), Mattei argues that when the state privatises, say, the railways, what it is really doing is expropriating the overall citizenry of a country of their common property – in this case, the railways – in much the same way the state expropriates a property from a private citizen or corporation. That is, as it privatises, a given government is not in fact selling that which belongs to itself, but that which belongs, pro quota, to each member of a community. And often without compensation at all to boot.

In his Italian book, Beni Comuni (the common goods), Mattei argues that when the state privatises, say, the railways, what it is really doing is expropriating the overall citizenry of a country of their common property – in this case, the railways – in much the same way the state expropriates a property from a private citizen or corporation. That is, as it privatises, a given government is not in fact selling that which belongs to itself, but that which belongs, pro quota, to each member of a community. And often without compensation at all to boot.

Mattei’s point ties in with the history of the commons, from Garrett Hardin’s famous article on The Tragedy of the Commons, often taken to be a rallying cry for privatisation (or, though it is rarely mentioned, for total government control), to its refutation by Elinor Ostrom (Mattei points out that Friedrich Engels had already demonstrated the fallacy in Hardin’s argument a hundred years before; see this piece in Italian on the matter). Mattei’s book is also connected to the centralization of the state William the Conqueror started from 1066 and the relevance, later on, of the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest, where a distinction was drawn between having and being (it is worth noting that the Magna Carta was really a document for the benefit of the nobility, against the crown, and it was the forest charter that codified some rights for common people – for instance, free access to the commons).

But Mattei’s point really has to do with the history of the enclosures, starting in the 15th century, and especially in the successive 3 centuries, as well as with the etymological perspective I have myself employed here. In particular, Mattei pays attention to the etymology of the word ‘private’, as in private property, which he claims is related to the meaning of ‘something being taken or subtracted’, and in such terms he finds much support in the arguments of scholars such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who in different ways had claimed that private property is always a case of theft of common goods. Add to this a discussion of the jurist William Blackstone on private property – namely, that private property is the exclusive and despotic domain of one person over something, to the exclusion of all others – and Mattei’s overall take is clear enough.

In the event, Mattei divides the common goods into 4 types, and each is argued to properly belong to everyone in a community, and not to a particular someone or company. To wit:

natural goods (water, air, the environment, etc.)

social goods (cultural goods, knowledge, historical memory, etc.)

material goods (public squares, public parks, gardens, etc.)

immaterial goods (such as the internet)

Regardless of what one makes of Mattei’s taxonomy of goods, it is certainly the case that the vast majority of his common goods constitute examples of industries and enterprises that originated in, and were developed by, the public sector and with public funds, often to be sold off to the private sector for private profit and in exchange for little or no compensation whatsoever – and oftentimes, moreover, these goods need to be recouped by the public sector, at great cost, when things go badly (or profiteering is abused).

Nevertheless, my point here, as I keep forgetting, is a linguistic one. How comes it that the concept to expropriate only applies from the private to the public and not the other way around, from the public to the private? And how comes it that the private usually receive compensation from the public but this is not always if ever the case in the other direction?

*****

This brings to an end this year’s collection of columns from me. How did I do? And did I keep to last year’s New Year resolutions? I intended to complete a couple of series on AI and fascism, which I did, though I wrote more about it than I had anticipated. I also wanted to write on some more controversial topics; or as I put it then:

I will sooner or later discuss the necessary “expropriation” of all rich people, followed possibly by a piece about the mental effects of using euphemistic expressions such as “the n-word” (namely, it has the same effects as if one were to utter/write the so-called n-word in full, always within a technical discussion of this and other verboten words), then maybe an article about the fact that no-one really “has pronouns” in any strict sense…

I have just written about expropriating all rich people, so at least I managed to get that in before the end of the year. But I have not written about the use of the n-word or the current obsession with pronouns – though, vaguely related to the latter, I did write about universality and diversity, and about how identities such as being a woman are partly relational (that is, they depend upon how others see you) and they are not entirely intrinsic (that is, a matter of self-identification). I had hoped for more engagement with the last two columns, as I had thought they would prove to be controversial or contested in certain circles, but them’s the breaks, I guess. God knows that the stuff on fascism always gets decent number of responses (including from pests), so perhaps I should keep to it in 2025.

I shall get back to the topics I had promised to engage with and haven’t yet in the new year, and I might intersperse these with a year-long review of Antonio Scurati’s four books on the rise of fascism, a book sensation in Italy but sadly not as well-known in the English-speaking world – that might make up for the crude analogies and just pisspoor scholarship on fascism from the likes of Timothy Snyder and Jason Stanley.

[i] I’m not joking; not long ago I bought a book about socialism at an Oxfam second-hand bookshop in London and the person selling it to me went ‘socialism? I had no idea people still talk about that sort of thing…’; the shop had loads of books on socialism on sale.

[ii] I pass in silence over the usual claim that particular individuals – think of your ‘genius billionaire’ here – really are responsible, all by themselves, for the immense the riches they are given.

[iii] And justice? Is justice possible under capitalism? Not according to three renown metaphysicians, to steal a quote from an ex-everything of mine:

(1) “There can never be justice on stolen land” (Krs-One)

(2) “All Property is Theft” (Proudhon)

(3) “Every man has a property in his own person” (Locke)

Therefore, the very existence of human beings and property rights negates the possibility of justice.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us gbyoing by donating now.