by Maniza Naqvi

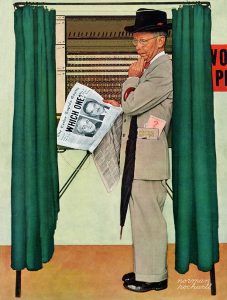

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

The idea and basis of the State is illustrated by artists through a rendition of this mythology for its first founding. The idea of State as we know it is based on this concept and definition of family and marriage in which there are unequal members: some to be served and others to serve; some to consume while others to produce; some to own and others to be owned; some to rule and others to be ruled; some to be strong and continuously strengthened by all means necessary and others to be weak and be weakened by all means necessary. All this a must for the good of the State—and the spirit vested into it through this definition of family. Read more »

My

My

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year. As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.  One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily.

One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily. In the Mood for Love

In the Mood for Love

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”