by Nickolas Calabrese

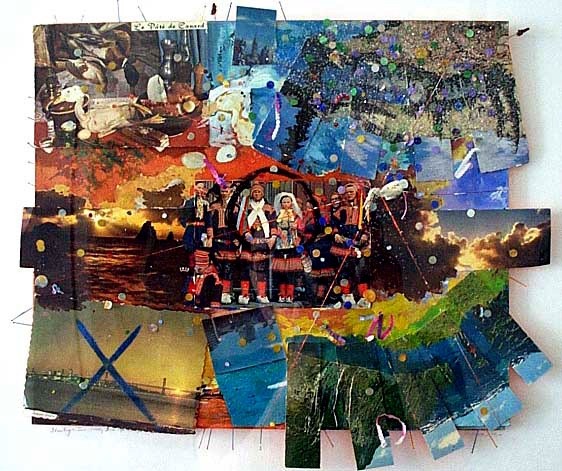

The subject of digital art is unclear. Work that was new five years ago can look ancient now because of the constant changes in technologies. The term “digital art” itself is an umbrella term that applies to a variety of names for art that is produced with the aid of a computer including, but is not limited to, “new media art”, “net art”, and “post internet art” (for a fuller linear history of the various terms that denote art made with or assisted by computers, see Christine Paul’s terrific introduction to A Companion to Digital Art reader, which she edited). The decision to use “digital art” is twofold. First, some of the alternatives only denote a temporal category while not actually referring to the form (new media can only be “new” for a brief period; it makes little sense for a “post internet” when it hasn’t significantly evolved from “net art”; put more brusquely, in the words of critic Brian Droitcour in Art in America magazine “most people I know think “Post-Internet” is embarrassing to say out loud”); and second, because I regularly teach an undergraduate visual arts course at NYU named Digital Art (a title I did not choose).

The upshot of digital art’s classification is that it might not actually exist as a category. Read more »

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a  The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car.

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car. I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”

I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it.

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it.

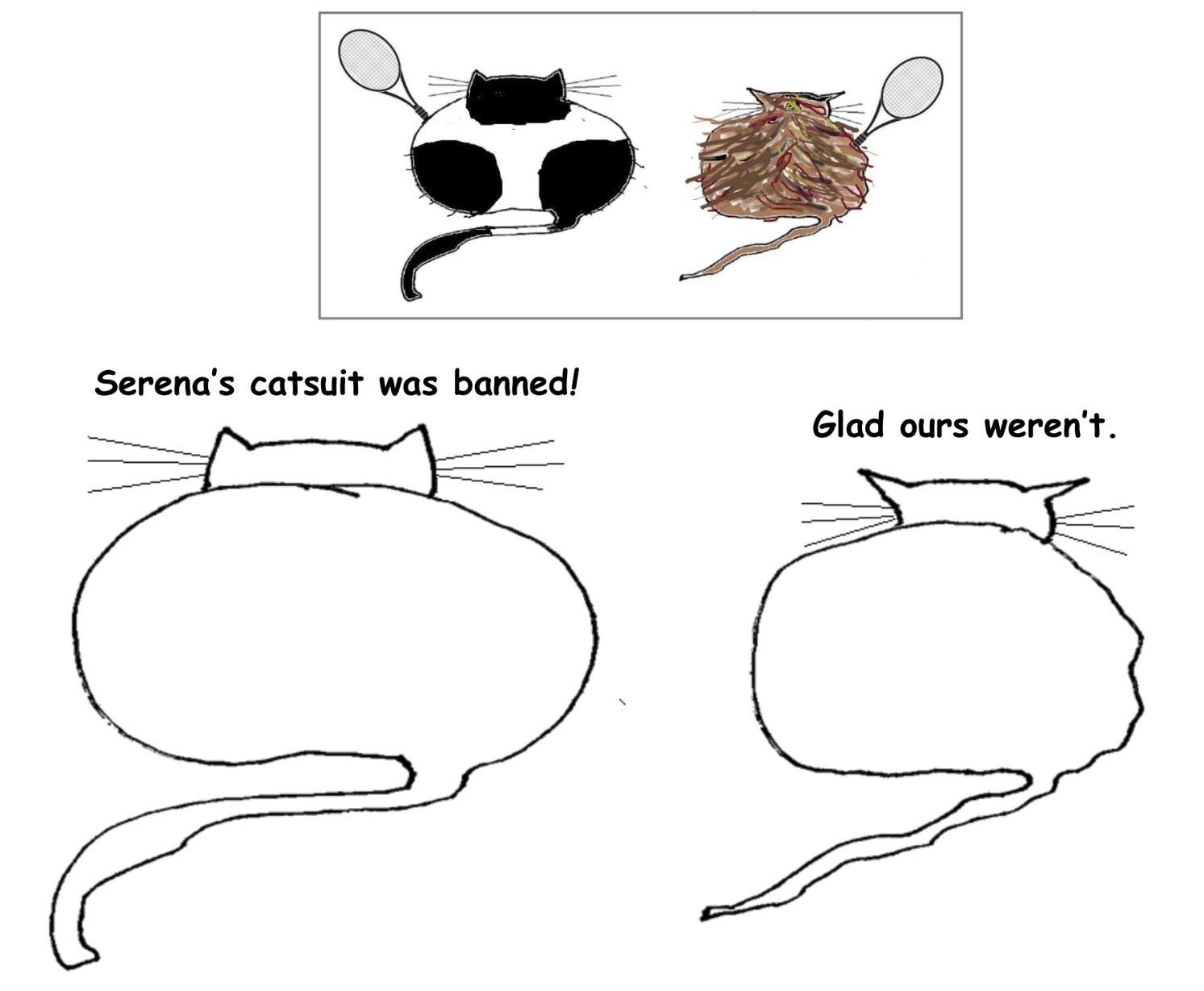

The controversy over the

The controversy over the