by Joan Harvey

Somewhere on an island with sun and shade, in the midst of peace, security and happiness, I would in the end be indifferent to whether I was or was not Jewish. But here and now I cannot be anything else. Nor do I want to be. —Mihail Sebastian

Fascism is what happens when people try to ignore the complications. —Yuval Harari

These days, even in the somewhat remote hills where I dwell, near a very liberal, and mostly white town, one thinks often about the possibility of living soon in an authoritarian state. And this possibility becomes impossible to separate from the idea of identity—who is most at risk? Probably not me. But certainly many immigrants are already or could be in danger, whether Mexican or Muslim. Identity, as in the quote from Mihail Sebastian above, becomes an issue when it is forced on one. And, tangled up with identity is the difficult issue of identity politics, which is driving the right in a negative way, and splitting the left.

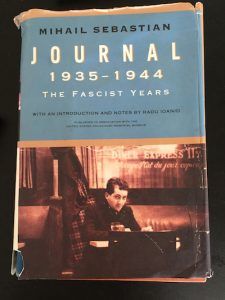

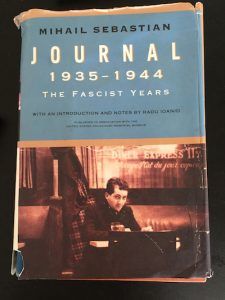

In his book The People vs Democracy, Yascha Mounk quotes sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield: “In most social interactions whites get to be seen as individuals. Racial minorities, by contrast, become aware from a young age that people will often judge them as members of their group, and treat them in accordance with the (usually negative) stereotypes attached to that group.” (Mounk, 2018, p. 202) Perhaps that is why one book keeps leaping to mind during these times, Mihail Sebastian’s Journal: 1935-1944, though it was written in very different circumstances. Radu Ioanid in his introduction writes: “One of Sebastian’s fundamental choices was to consider himself a Romanian rather than a Jew, a natural decision for one whose spirit and intellectual production belonged to Romanian culture. He soon discovered with surprise and pain that this was an illusion: both his intellectual benefactor and his friends ultimately rejected him only because he was Jewish.” (Sebastian, 2000, p. xii)

When the entries in this journal begin, Sebastian is in his late twenties. His life is full of literary feuds, theater going, agonies over his work, women chasing him and women he chases, and his passion for music, music, music. There are Mozart sonatas on the radio, plans to go skiing, lovely descriptions of his “amatory sufferings,” intelligent reading of Proust. He often meets and dines and parties with friends. But as the Germans pick up steam, the anti-Semites in Romania are emboldened; because he is Jewish he’s no longer allowed to practice law, the plays he writes are not produced, he loses his job with the Writer’s Association, he has no money to pay the rent and soon he’s not allowed to live in his apartment anyhow. Read more »

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights. Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

The German philosopher

The German philosopher  The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor? Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy? He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth. I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.