“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

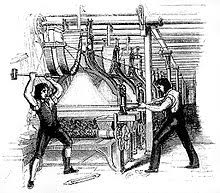

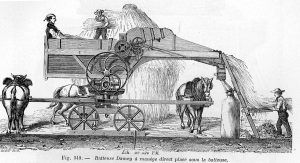

The original Luddites were English textile workers in the Midlands and the North who organized themselves in secret and destroyed machines in the newly established factories and mills. They were called “Luddites” after their fictitious leader, “General Ludd.” Peak Luddism occurred around 1812-1813, although there were incidents of machine breaking before and after then. The most notable of these were the Swing riots that swept across parts of Southern England in 1830 when impoverished agricultural labourers, sometimes carrying out threats issued by the fictitious Captain Swing, smashed threshing machines, burned barns, and demanded higher wages.

A common view today of these machine-breakers in the early stages of the industrial revolution is that they represent a clearly futile attempt to block technological innovation. One can sympathize with their plight, of course. Weavers who were proud of skills they had spent years mastering could now be replaced by relatively unskilled workers operating the new machines. Agricultural labourers who counted on threshing with hand flails for several months of employment following the harvest now faced winters without work or wages. But the times they were a-changing. Quite simply, the new methods of production could produce much more in less time and at lower cost. Trying to halt progress of this sort is as pointless as ordering back the tide. Resistance is futile.

But this view of the people who smashed stocking looms and threshing machines is oversimplified and somewhat unjust. It also carries some questionable ideological freight. Let me explain. Read more »

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow. One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism. The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As  A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with  In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.