by Ali Minai

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Broadly speaking, there are two overlapping approaches that account for most of the work done in the field of AI since its inception in the 1950s – though, as I will argue, it is a third approach that is likelier to succeed. The first of the popular approaches may be termed algorithmic, where the focus is on procedure. This is grounded in the very formal and computational notion that the solution to every problem – even the very complicated problems solved by intelligence – requires a procedure, and if this procedure can be found, the problem would be solved. Given the algorithmic nature of computation, this view suggests that computers should be able to replicate intelligence.

Early work on AI was dominated by this approach. It also had a further commitment to the use of symbols as the carriers of information – presumably inspired by mathematics and language. This symbolic-algorithmic vision of AI produced a lot of work but limited success. In the 1990s, a very different approach came to the fore – though it had existed since the very beginning. This can be termed the pattern-recognition view, and it was fundamentally more empirical than the algorithmic approach. It was made possible by the development of methods that could lead a rather generally defined system to learn useful things from data, coming to recognize patterns and using this ability to accomplish intelligent tasks. The quintessential model for this are neural networks – distributed computational systems inspired by the brain. Read more »

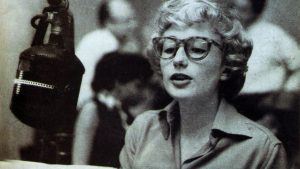

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

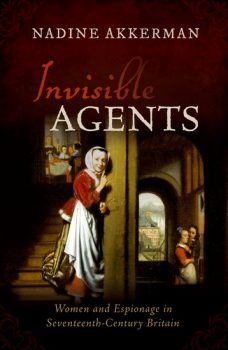

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature. History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events. A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann) impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.