by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Epictetus’ Enchiridion 52 is an exercise in metaphilosophy. It captures the double-vision students of Stoicism must have about their own progress. The core insight of E52 is that the tools of philosophical inquiry and progress toward insight can themselves become impediments to progress. E52 is the last entry of the Enchiridion in Epictetus’ own words (with E53 being inspirational quotations from Cleanthes, Euripides, and Plato), and in it, a decidedly practical program is endorsed. The key to this endorsement is the contrastive case Epictetus makes. Here is E52 in its entirety:

[1] The first and most necessary subject in philosophy is the application of philosophical principles, such as ‘Don’t be a fraud’. The second is that of proofs, such as why it is that we ought not to be frauds. The third subject is that which confirms and articulates these proofs, such as, how is this a proof? For, what is a proof? What is inference? What is contradiction? What is truth? What is falsehood?

[2] Therefore, the third subject is necessary because of the second, and the second is necessary because of the first. But the most necessary and the one where we must linger is the first. Yet we do it backwards, because we devote time to the third subject and entirely busy ourselves with it, while we completely neglect the first. Consequently, we’re frauds, but we’re ready to prove that we ought not to be frauds.

The problem, of course, is the last sentence: though we have proofs we should not be frauds, we nevertheless are frauds. How, given the Stoic program of philosophical training – that we have the proofs precisely in order to remind ourselves not to be frauds – does this result come about? And more importantly, how, with these tools, can we prevent it? Read more »

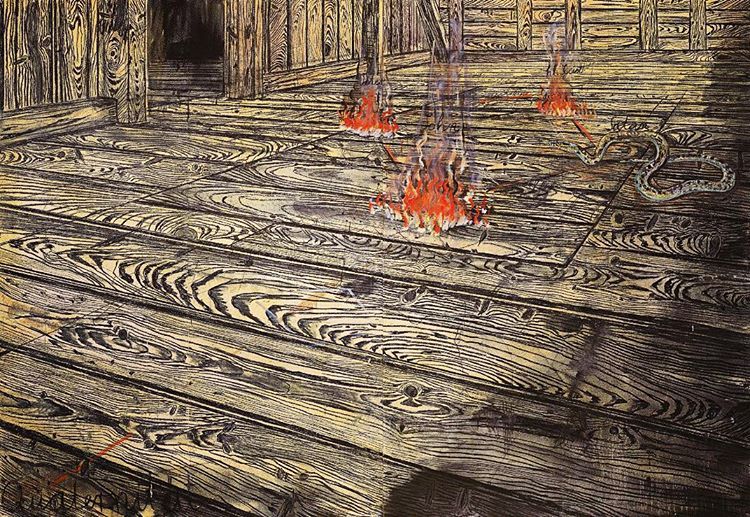

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

Last time

Last time It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].

It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1]. A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

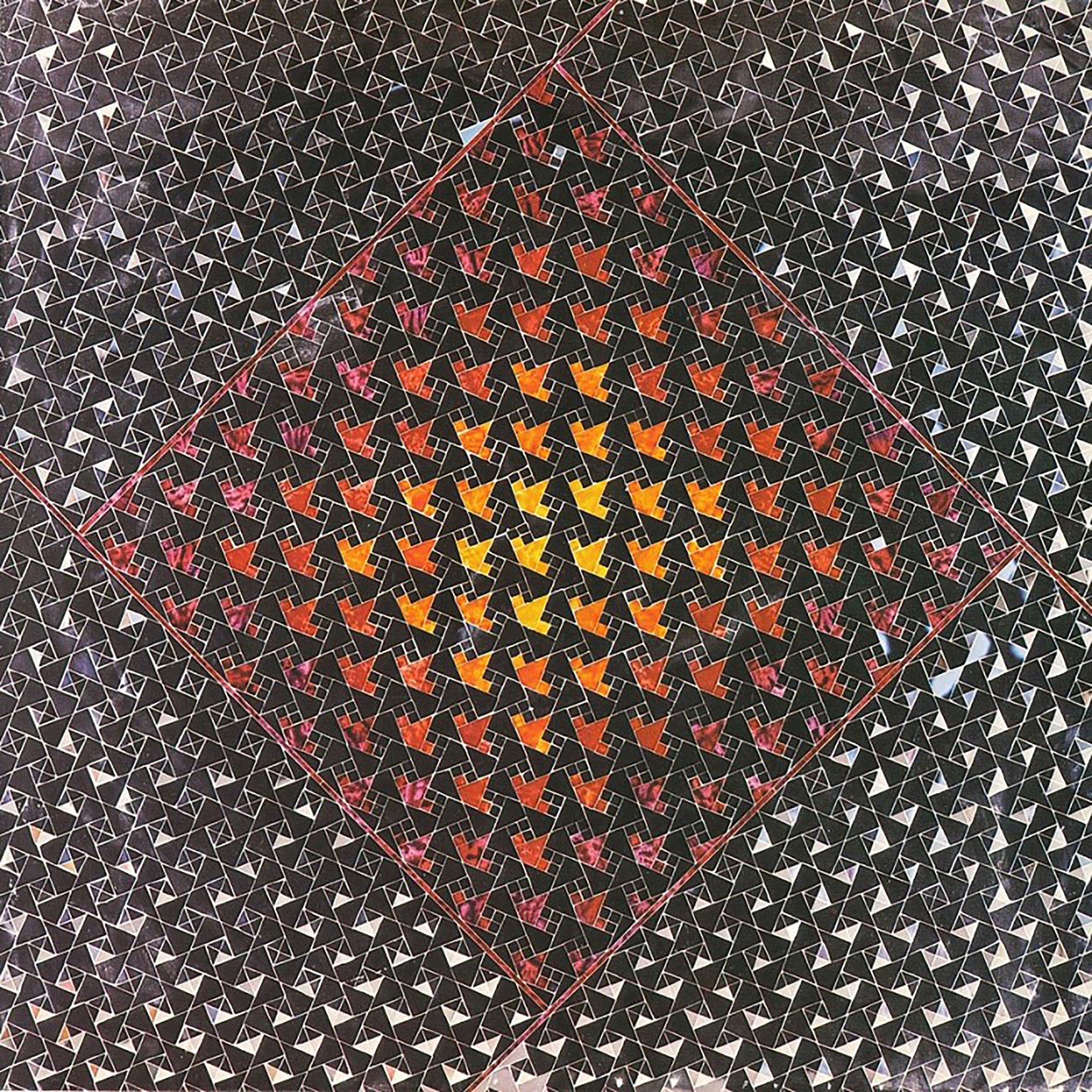

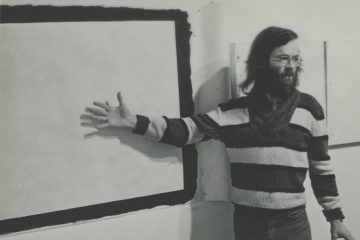

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death?

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death? This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.

This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.  Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.