by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard:

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard:

Hier ist der Deutschlandfunk, heute aus der Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee.

It wasn’t the fact that the station was transmitting country music, a treat for the Virginia girl far from home. It was the announcer’s voice that enthralled me and the language it spoke. There was an elegance, a muted, dependable deep resonance, a flow of words with a rhythmic logic that made me long to be able to speak that way. It sounded noble, above the fray, measured and meaningful. I could imagine that voice reciting Shakespeare or Schiller or Rilke.

This was not the ‘Achtung!’ German most Americans know from movies about the Nazis, or newsreels of Hitler speeches, or parodies of authoritarian figures in uniform. And despite the subject at hand—a country music broadcast—the voice-over did not try to mimic the jovial downhome twang of the good-ole-boy announcer from my deep South. It could just as well have been narrating a classical music concert from an ‘opry’ closer to home.

I added German to my bucket list that day. Read more »

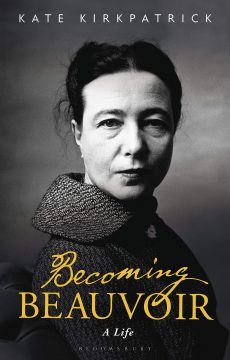

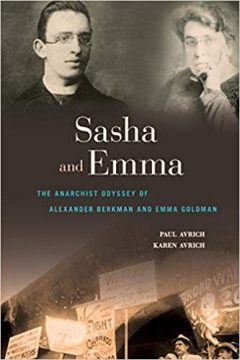

by Adele A Wilby

Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir.

Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir.

The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

There is literature available on these issues, but Goldman and Beauvoir were prepared to live the principles they espoused in the early twentieth century. For both women, freedom was central to their thinking and shaped the way they lived their lives. Consequently, their personal relationships were unconventional: they had many lovers and loves, including, in the case of Beauvoir, female lovers. Nevertheless, they were able to sustain a relationship with one man in particular throughout their lifetimes: Alexander Berkman in the case of Emma Goldman, and Jean Paul Sartre in the case of Simone de Beauvoir. Commenting on her first encounter with Berkman, Goldman says, ‘a deep love for him welled up in my heart… a feeling of certainty that our lives were linked for all time’. Beauvoir also identified something special in her meeting of Sartre: she was prepared to enter into a ‘pact’ with Sartre that was premised on a love for each other. The ‘pact’ would separate their relationship from ‘lesser’ lovers: their love would be what Sartre termed an ‘essential love’, and they were then free to pursue their open relationship unburdened of the constraints of monogamy and marriage.

However, as we learn from Avrich and Avrich and Kirkpatrick the sexual relationship between these enduring couples eventually came to an end. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously?

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously?

Consider Larry Niven’s 1971 take on that question. In a fitting contrast to the infinite multiplication of actions implied by the existence of a quantum multiverse, his story, “All the Myriad Ways”, consists entirely of a solitary police detective sitting alone and trying to puzzle out why a rash of unexplained suicides has accompanied the discovery of multiple, parallel universes. He begins to think that people see the existence of a world corresponding to every possible choice they might make as undermining the idea that they have any choice at all. In the end, he puts his own gun to his head – and all of the possible outcomes of that occur at once. I think there is more than one way of understanding this story. It’s not necessarily that people are inspired to take a fatalistic attitude by the knowledge of other worlds, it’s that just by recognizing that suicide is one of the possible outcomes, it becomes one of the things that will happen in some world or another.

But there may be a basic misunderstanding about quantum parallel universes lurking there. The splitting of universes has nothing to do with you and your decisions. Subatomic quantum events cause the universe to split, not you. You can, however, cause the universe to split whenever you make a decision by tying that decision to a quantum event. There’s an app for that. (Warning! This app only works if the MWI of Quantum Mechanics is correct.) Anyway, in the end, it’s not clear that it matters what causes the universe to split since it is splitting so often and so fast that it should create plenty enough parallel universes to cover all the decisions you could possibly make.

How should you feel about this? Read more »

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

by Akim Reinhardt

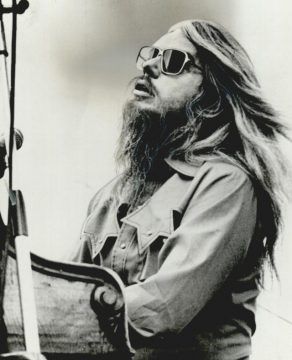

He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.

He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.

In addition to recording his own music, Leon Russell was a prolific session musician who worked with hundreds of artists over six decades. His main instrument was piano, but he played everything from guitar to xylophone. Russell was also was a songwriter who contributed to other musicians’ oeuvres. His song “This Masquerade” has been recorded by over 75 artists. “A Song For You” has been recorded by over 200. Finally, he was a record producer, a mastermind behind the glass and in front of the mixing board who oversaw and orchestrated, literally and metaphorically, the artistry of others. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

S. C. Gwynne’s “Hymns of the Republic” is an excellent book about the last, vicious, uncertain year of the Civil War, beginning with the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864 and ending with the proper burial of the dead in Andersonville Cemetery in May 1865. The book weaves in and out of battlefield conflicts and political developments in Washington, although the battlefields are its main focus. While character portraits of major players like Lee, Grant, Lincoln and Sherman are sharply drawn, the real value of the book is in shedding light on some underappreciated characters. There was Clara Barton, a stupendously dogged and brave army nurse who lobbied senators and faked army passes to help horrifically wounded soldiers on the front. There was John Singleton Mosby, an expert in guerilla warfare who made life miserable for Philip Sheridan’s army in Virginia; it was in part as a response to Mosby’s raids that Sheridan and Grant decided to implement a scorched earth policy that became a mainstay of the final year of the war. There was Benjamin Butler, a legal genius and mediocre general who used a clever legal ploy to attract thousands of slaves to him and to freedom; his main argument was that because the confederate states had declared themselves to be a separate country, the Fugitive Slave Act which would allow them to claim back any escaped slaves would not apply. Read more »

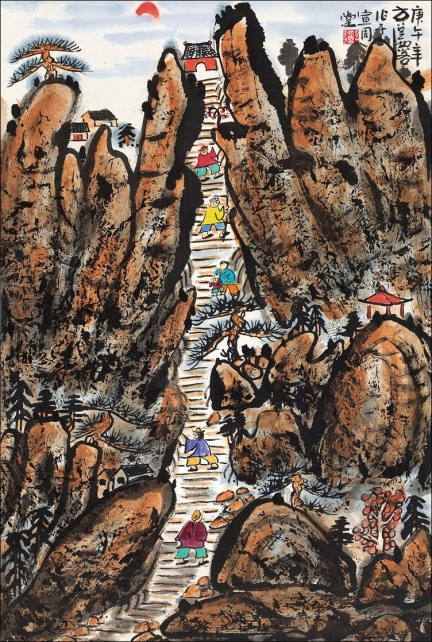

.

takes many steps to top this mountain

as if Olympus

a prickly pine’s upon one nub

as if Zeus

pagoda house shed

as if Many Mansions

sky sun red some blue

as if Noon

some on steps are climbing

as if To move

calligraphy top right

as if A thought balloon

each stone makes this mountain higher

as if No problem nihil est

as if

A scene of sheer improbable

as if

It’s just imagination I guess

‘

Jim Culleny

1/24/18

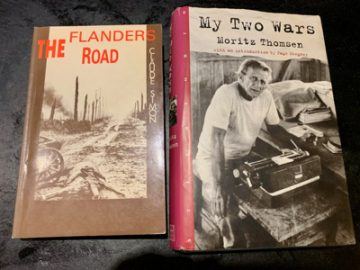

by Joan Harvey

On this last Veterans Day, a young friend shared an essay on Facebook by veteran Rory Fanning about his wish that Veterans Day, which celebrates militarism, be changed back to Armistice Day, to celebrate those working for justice and peace. I hadn’t known that Armistice Day, which was established after WWI, had been replaced in 1954 by Veterans Day. Veterans Day, Fanning writes, “instead of looking toward a future of peace, celebrates war ‘heroes’ and encourages others to play the hero themselves. . . going off to kill and be killed in a future war—or one of our government’s current, unending wars.”

My father enlisted the first day America joined WWII, but he almost never talked about his experience. I heard about WWII mostly from my grandparents who were active in the Austrian Resistance, and in my twenties, at the urging of a Native American man I knew, I read book after book on the Holocaust. It is hard not to believe that WW II was one of the few necessary and just wars. But in this war, as in all wars, men were used senselessly, and the experience of the men fighting was often less that of achieving a clear useful goal and more of mismanaged chaos.

I’ve concurrently been reading a biography of Napoleon and listening to War and Peace. Being neither a war nor a history buff, I read descriptions of battle after battle and look at diagrams of landscapes with arrows and dots, with very little real comprehension of the topography and maneuvers and strategies implemented. But it is impossible to come away from both books without the sense of the millions of lives rapidly, brutally, and very often meaninglessly expended, the millions of young men offering themselves up to be butchered or die of disease or cold or starvation. And these descriptions recalled to my mind two great, but not much read, writers who wrote about fighting in WWII, and who gave me the strongest sense of what combat in that war was like. Read more »

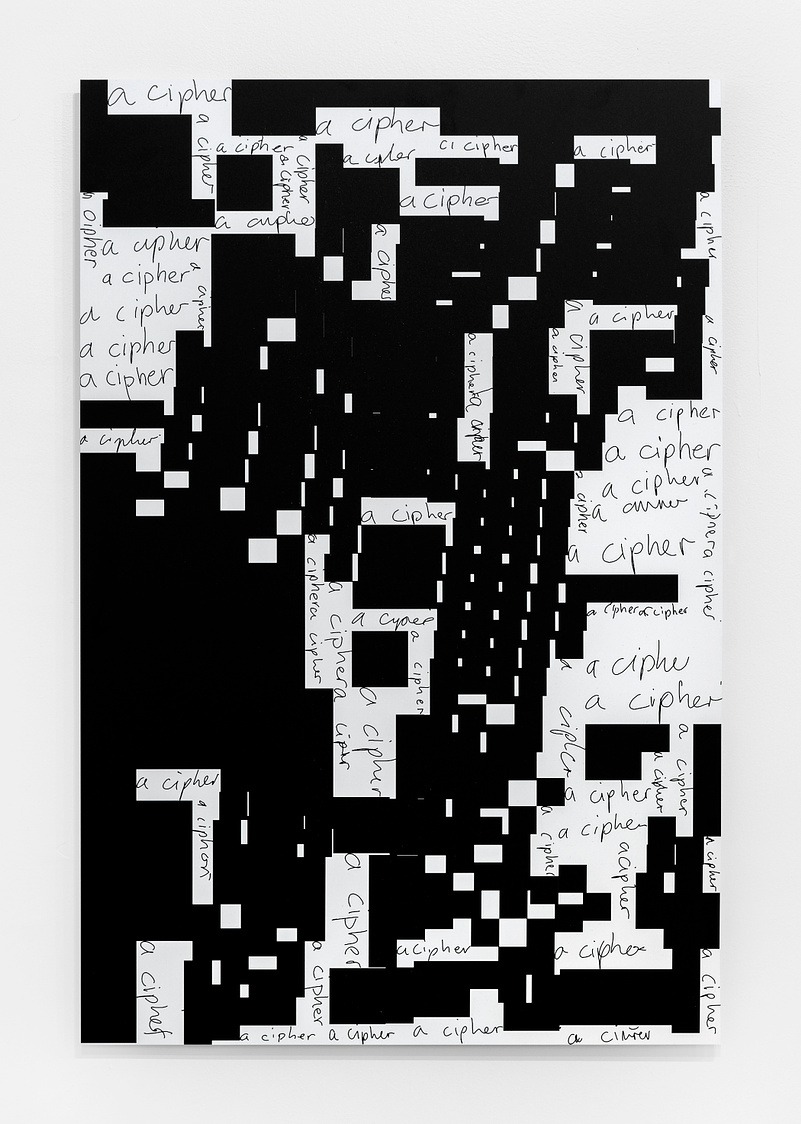

Damon Zucconi. A Cipher, 2019.

Handwriting synthesis, 2d bin packing, UV curing ink on Alu-dibond.

by Charlie Huenemann

“There’s only one rule I know of, babies — ‘God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.’” —Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

Despite Vonnegut’s strong counsel to babies entering the world, kindness seems to be in short supply. Little wonder. Our news media portray to us a world of power politics, corporate greed, murders, and cruel policies which are anything but kind. Our popular forms of entertainment, much more often than not, are stories about battles that shock and thrill us and gratify our lust for bloody vengeance, leaving no room for wimpy, kind sentiments. Success is advertised to us as requiring harsh discipline, dedication, and focus, and kindness, it appears, need not apply. Even though we all like to give and receive kindnesses, they seem to play no role in our political, social, and cultural economies.

Despite Vonnegut’s strong counsel to babies entering the world, kindness seems to be in short supply. Little wonder. Our news media portray to us a world of power politics, corporate greed, murders, and cruel policies which are anything but kind. Our popular forms of entertainment, much more often than not, are stories about battles that shock and thrill us and gratify our lust for bloody vengeance, leaving no room for wimpy, kind sentiments. Success is advertised to us as requiring harsh discipline, dedication, and focus, and kindness, it appears, need not apply. Even though we all like to give and receive kindnesses, they seem to play no role in our political, social, and cultural economies.

We might be misled into thinking of kindness as bound up with ethereal virtues, such as a pervasive love for all humanity, or a spiritual peace from the heart that passes all ordinary understanding. To advocate for this sort of kindness sounds like recruiting for some mystical cult. But ordinary experience tells us that kindness is neither magical nor extraordinary. It’s an everyday thing. You and I meet in the street, and I say, “That’s a cool shirt!” and you say, “Thanks! Kind of you to say so.” A teacher hears out a student’s tale of woes, and grants an extension on a paper out of kindness. You slow down to allow another car pull into traffic, and get a cheery wave in reply. And so on, through many instances of life, in all sorts of ways. Being kind does not require being Gandhi. It doesn’t even require love. It just requires a bit of, well, kindness.

Kindness, I think, does not require spiritual attunement, but requires only patience and empathy. Read more »

Dr. Benjamin Ebert is remarkable for his leadership in describing the genomic landscape of adult myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), including identifying critical new roles for ribosomal dysfunction. His laboratory discovered the molecular basis of lenalidomide activity in MDS as well as multiple myeloma. Recent studies have identified clonal hematopoiesis and its contribution to both hematologic malignancies and cardiovascular disease. Along with human genetic studies, Dr. Ebert’s lab has made significant contributions to understanding the biological basis of the transformation of hematopoietic cells by somatic mutations. Currently, he is chair of the medical oncology department at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Jeroen Bouterse

In a radio sketch by the British comedians David Mitchell and Robert Webb, David Mitchell plays an interviewer trying to get a cabinet minister to say what he really thinks about the government’s funding cuts. At first, Robert Webb, playing the minister, says there is no disagreement between him and the cabinet, but the interviewer presses on, continually repeating the same question: “OK …. but what do you really think?”

In a radio sketch by the British comedians David Mitchell and Robert Webb, David Mitchell plays an interviewer trying to get a cabinet minister to say what he really thinks about the government’s funding cuts. At first, Robert Webb, playing the minister, says there is no disagreement between him and the cabinet, but the interviewer presses on, continually repeating the same question: “OK …. but what do you really think?”

At one point, the minister unrealistically breaks under these faux-critical questions, and admits:

“It’s all lies. I hate it, I’m against it, all right? […] That’s it, my career is over.”

You’d think that was enough. But after a pause, the interviewer replies:

-“Yes, but what do you really think?”

“Look, it’s all futile. We’re all nothing but specks of flesh going through this obscene dance of death for nothing. Everything is nothing.”

-“….Thank you minister.”

I associate nihilism with existential honesty, a recognition of truths about our world and our lives that goes beyond personal, social or political honesty, that cuts through all webs of meaning that we have spun for ourselves and sees them for what they are: vanishingly thin threads in an infinite void. As such, nihilism seems to me very much the final word on human existence. The only thing is that it is such a transcendental, ‘cosmic’ claim that it doesn’t really connect to any aspect of our own lives, petty or heroic as they are. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas O’Dwyer

The Prophet was sleeping when the call to afternoon prayer rang out across the town. He woke and reached for his prayer robe but a cat was curled up on an outstretched sleeve. A servant moved to shoo the animal away, but the Prophet raised his hand and motioned for the servant to bring scissors. Rather than wake the dozing cat Muezza, who had once killed a venomous snake that had threatened the Prophet, he sliced the sleeve off his robe, leaving the cat undisturbed. This legend of the warrior Mohammed and Muezza is one of the earliest records of a man’s love for a cat. Mohammed’s attitude to cats has meant that they have fared better under Islam than in other religions.

Ancients Egyptians had made cats divine and punished even the accidental killing of a cat with death. Islam instructs Muslims to revere cats and warns that mistreating a cat is a serious transgression. A 44-year-old ambulance driver, Mohammed Alaa al-Jaleel, became an internet sensation as the “Cat Man of Aleppo.” He risked his life to stay in the embattled Syrian city to rescue and care for distressed cats. His first cat sanctuary was bombed and gassed during the siege of the city. In the tradition of Muslim cat lovers, he ignored the danger from fierce fighting and bombing to care for hundreds of stray cats, often digging them out of wrecked buildings. Read more »

halmas sheen

athann soor

dilas shishargaanth

—By Aliya Nazki

Snow furrows my phiran

Ashes: my hands

Icicle: my heart

Aliya Nazki, a Presenter at BBC Urdu, based in London, was born and raised in Kashmir.

Translated from the Kashmiri by Rafiq Kathwari /@brownpundit

by Claire Chambers

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore. Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary celebration was taking place nearby about a month later, on 12 November 2019, so I guessed their final destination was Nankana Sahib, Guru Nanak’s birthplace. The British-Indians’ presence was a reminder, if any were needed, of Punjabiyat’s close binds. To take another example, after the violence of the 1984 raid (known as Operation Blue Star) of Amritsar’s Golden Temple, some Sikhs took refuge in villages just across the border in Pakistan. It is unsurprising, then, that in Imagining Lahore, one of the best-known recent books about the ancient West Punjabi capital, Haroon Khalid takes pains amid rising Islamization to stress the region’s earlier Sikh rulers and the present-day city’s neglected gurdwaras and crumbling havelis.

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore. Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary celebration was taking place nearby about a month later, on 12 November 2019, so I guessed their final destination was Nankana Sahib, Guru Nanak’s birthplace. The British-Indians’ presence was a reminder, if any were needed, of Punjabiyat’s close binds. To take another example, after the violence of the 1984 raid (known as Operation Blue Star) of Amritsar’s Golden Temple, some Sikhs took refuge in villages just across the border in Pakistan. It is unsurprising, then, that in Imagining Lahore, one of the best-known recent books about the ancient West Punjabi capital, Haroon Khalid takes pains amid rising Islamization to stress the region’s earlier Sikh rulers and the present-day city’s neglected gurdwaras and crumbling havelis.

As ever, the trip from the airport afforded a veritable binge for the eyes. I made my way through the Beijing Underpass with its sign wishing the Pak-China Friendship a long life. Other less geopolitically-named channels evoked poets Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Waris Shah, emphasizing Lahore’s rich and proud literary culture.

Whereas I have written in a few different places about British chicken shops being an alphabet soup from AFC to ZFC, in Lahore I saw Yasir Broasts and Fri-Chicks. Passing the brightly-lit shopfront of Cakes & Bakes made my mouth water. Meanwhile, educational institutions had equally imaginative handles, including Success College and the Bluebells School. Read more »

Offices of the Brenner Base Tunnel project in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol. When completed, this will be the longest train tunnel in the world, stretching 64 kilometers (40 miles) between Innsbruck and Franzensfeste. It is more than 580 meters (1900 feet) below the surface as it passes underneath the border of Austria and Italy at the Brenner Pass in the Tyrolean Alps. Photo taken in November, 2019. Click here for more info.

by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a new weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost.

Either way, in 1971 Spencer went out for a magazine and never came back. When friends tracked him down several days later, they found he’d joined a small, new, secretive religious group called Children of God. Today it’s known as The Family International, and infamous for being the cult that the Phoenix children (including River and Joaquin) grew up in. According to Wikipedia, anyway, Spencer is still a member.

Prior to joining Children of God, Spencer had been a member of something else: Fleetwood Mac. And his departure from the band marked the second time in less than a year that one of their original guitarists had left to find God. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

Harari advances these arguments with great confidence. Yet they are far from conclusive. Read more »