by Thomas O’Dwyer

The Prophet was sleeping when the call to afternoon prayer rang out across the town. He woke and reached for his prayer robe but a cat was curled up on an outstretched sleeve. A servant moved to shoo the animal away, but the Prophet raised his hand and motioned for the servant to bring scissors. Rather than wake the dozing cat Muezza, who had once killed a venomous snake that had threatened the Prophet, he sliced the sleeve off his robe, leaving the cat undisturbed. This legend of the warrior Mohammed and Muezza is one of the earliest records of a man’s love for a cat. Mohammed’s attitude to cats has meant that they have fared better under Islam than in other religions.

Ancients Egyptians had made cats divine and punished even the accidental killing of a cat with death. Islam instructs Muslims to revere cats and warns that mistreating a cat is a serious transgression. A 44-year-old ambulance driver, Mohammed Alaa al-Jaleel, became an internet sensation as the “Cat Man of Aleppo.” He risked his life to stay in the embattled Syrian city to rescue and care for distressed cats. His first cat sanctuary was bombed and gassed during the siege of the city. In the tradition of Muslim cat lovers, he ignored the danger from fierce fighting and bombing to care for hundreds of stray cats, often digging them out of wrecked buildings.

The domestic cat is not mentioned in the Jewish Bible. Its big brother the Lion of Judah, the emblem of Jacob’s son, is prominent and remains on the coat of arms of the city of Jerusalem. In an ancient Hebrew text, Perek Shirah, a cat is portrayed as praising God with a verse from Psalm 18: “I have pursued my enemies and overtaken them: neither did I turn back until they were consumed” – a neat description of a hunting cat. The Talmud mentions cats favourably as symbols of virtue and cleanliness (they buried their waste). Jews historically had a practical view of cats – a synagogue would keep a cat to hunt rats and protect parchment texts from mice. Hinduism has a cat goddess, Shasti, but Indians have generally regarded cats with disdain for being dirty, violent and unlucky. Nevertheless, killing or injuring a cat is considered sinful.

With some irony, it is Christianity, the religion of love, forgiveness and redemption, that has the most brutal record of hatred and cruelty against cats. They became associated with the devil and were considered the familiars of witches and Satan worshippers. In 1233, Pope Gregory IX issued an official papal decree, Vox in Rama, declaring that Satan was half-cat and often took the form of a cat during Satanic masses. Cats were brutally tortured to death and thrown alive on fires. The cats were later said to have achieved posthumous revenge with Black Death of the 13th century when plague-bearing rats with fleas overran Europe. There were no cats left to kill them.

Medieval “witches” were no more than harmless older women who kept cats as company and to kill rats and mice around the home. This brings us to the interesting question of why, in popular mythology, there are crazy cat-ladies and no crazy cat-men. Since most ancient societies and religions were patriarchal, it was largely men, not women, who reacted with the increasingly domesticated global population of small cats. In modern times, thousands of prominent men in every walk of life have openly owned and loved cats as much as any spinster-woman stereotype.

A gritty 1975 documentary, Grey Gardens, featured two reclusive and formerly upper-class spinster ladies. They were relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy-Onassis who lived in squalor and degradation in a crumbling East Hampton mansion. The house was filled with cats, raccoons and rats, cementing the crazy cat-lady stereotype in the popular imagination. The Simpsons continued the chauvinistic trope with their character Eleanor Abernathy, known as the Crazy Cat Lady. Abernathy had a law degree from Yale and a medical degree from Harvard before turning to alcohol in her thirties and becoming a raving, cat-hoarding lunatic. So where are there crazy cat men? There is a hint in the gender stereotype that a man who likes cats must be, well, unmanly. He could therefore also be regarded as a “crazy cat-lady,” much as whiny, gossipy men were deemed to be “old women.” Such a misogynistic segue would seem to be necessary to prevent us from calling out cat lovers like Mohammed, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill and Ernest Hemingway as “unmanly.” Perish the thought, and wait for science to come to the rescue.

In August this year, the journal Royal Society Open Science reported that researchers at UCLA had analysed more than 500 pet owners and found nothing to support any crazy cat-lady stereotype. The study observed how people reacted to distress calls from animals and compared pet ownership with mental health-related or social problems. The conclusion was straightforward – owning lots of cats does not make you mad, sad or anxious. “We found no evidence to support the ‘cat-lady’ stereotype: cat-owners did not differ from others on self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety or problems in close relationships,” the study said. “Our findings, therefore, do not fit with the notion of any cat-owners being more depressed, anxious or alone.”

Cute cats may seem to have become a tiresome meme peculiar to the internet’ s social media. But Peggy Gavan, in her recent book The Cat Men of Gotham: Tales of Feline Friendships in Old New York, says a cat obsession was evident decades ago. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, thousands of feral cats were rounded up and gassed in New York, supposedly for humanitarian reasons. Poor children were paid a nickel per cat caught, which meant that hundreds of healthy pets were also slaughtered. Gavan’s book documents how many New Yorkers pushed back and saved many cats by publicising the good that cats did. “In the late 1800s, early 1900s, every time a cat did something – saved its family by meowing at a fire, or was rescued by a police officer, or something like that – it always made the headlines,” Gavan writes.

Although Gavan is undoubtedly a genuine cat-loving woman, her book is mostly about cat-loving men banding together to protect the creatures. She writes that the gender norms of this time, before World War I, kept women at home and out of workplaces that feature in the stories of cat rescues. The press too was male-dominated, so it was men who wrote the articles about men engaging with cat exterminators. There are few “cat-women” in the news articles that she researched for her book.

“Every police station, every firehouse, had a cat. You had hundreds of cats down at the post office,” Gavan writes. “Most businesses, restaurants, hotels, had cats because they controlled the mice and the rats. Cats would just do more things. And the ‘cat men’ would always call the press and make a big deal out of it.”

For example, the huge Brooklyn shipbuilding yard was infested with thousands of rats in the late 1800s, causing damage to the docks and equipment. The US Navy tried to deploy dogs against them, but they were terrified of the rats. Workers managed to attract scores of cats to the yard and the rats were brought under control. One newspaper wrote that a ratter named Minnie “deserves a gold medal for preserving the property of the United States people.”

If we seek genuine crazy (if fictional) cat-men, we must look to the movies for this other gender stereotype. Heroes may love good dogs, but a world-conquering mastermind is a cat person. He will own a large hairy cat, all black or all white. The villain slowly strokes the cat on his lap in a way that looks more menacing than comforting while he explains how he is going to dismember the Hero and destroy the planet. The villain’s cat is an evil accessory descended from the witch’s familiar. It is superior, other-worldly, and the perfect adviser to someone taking over the world, probably because cats have already done it.

The origin of the evil plotter-and-cat theme was Cardinal Richelieu, the 17th-century power behind the French throne, and villain of The Three Musketeers. The cardinal was such devotee of cats – he owned 14 at the time of his death – that he made their adoption as companions fashionable in French society. Richelieu had a cattery built at his residence, the Palais-Royal, where he kept his mostly Persians and Angoras. He always had a cat on his lap as he worked, and most artwork pictures him petting a white cat while scheming. Any resemblance to Ernst Blofeld (Donald Pleasence) evilly stroking a white Angora on his lap in You Only Live Twice is probably not coincidental. Aside from movie villains and their right-hand cats, the tales of real-life heroic or simply interesting men and their cats are just as intriguing. They give the lie to the odd concept that the cat is predominately a pet for lonely women.

It was long believed that cats were first domesticated in Egypt, given the extensive evidence found there. But in 2003, French archaeologists found the carefully buried remains of a human and a cat, along with seashells, polished stones, and other decorative artefacts, in a 9,500-year-old grave on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. This find, in a Neolithic village, predates early Egyptian cat art by more than 4,000 years. Cats were not native to Cyprus – local legend says they were imported in the fourth century to control snakes and rodents. The modern breed of Cyprus cat has features similar to Egyptian cats. Medieval documents suggest that a statue of Bastet, the Egyptian cat god, once stood on the Cape of Cats on the south coast of the island, facing towards Egypt.

Shortly after the era of Mohammed, an unknown ninth-century Irish scribe in an Austrian monastery wrote a delightful short poem about his cat in Old Irish, in the margin of a manuscript. It is the first named personal cat in European literature – Pangur Bán, “white Pangur.” In eight verses of four lines each, the author compares the cat’s happy hunting with his own scholarly search for the right words.

I and Pangur Bán, my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

In the details of men who have been fond of cats, artists and writers predominate. It is idle to speculate why, beyond noting the many quotes from those who say the small and discreet cat is an ideal companion for those doing solitary work, like the ninth-century Irish monk. Ernest Hemingway was the most widely known literary cat lover. A boat captain once gave Hemingway a white six-toed cat, and the Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West still has 40-50 six-toed cats. (Cats normally have five front toes and four back toes). The cats carry the six-toe gene in their DNA and are not a separate breed like the tailless Manx, but are a mix of calicos, tabbies, tortoise-shells, blacks and whites.

In his will, British war-leader Winston Churchill requested that a ginger cat named Jock must always reside at his family home of Chartwell. The original Jock was on Churchill’s bed when he died at the age of 90. The cat lived another ten years and Churchill’s wishes have been honoured since – Chartwell now has a ginger Jock VI. Cats were never far from Churchill. His staff said that during World War II he often groomed and chatted to his grey cat Nelson while he pondered military tactics. In 1941, Churchill went to meet President Theodore Roosevelt to ask for military aid. As he disembarked, a small black cat approached him and Churchill stooped to pat the cat before greeting the American officials, creating the winning photograph from the trip.

Among many American leaders with a fondness for felines, Abraham Lincoln was the most notable. When he was elected president, Secretary of State William Seward surprised him with a gift of two kittens, Tabby and Dixie. The cats were rarely far from his side. He once fed Tabby at the table during a formal White House dinner. When his wife Mary chided him that this was “shameful in front of their guests,” Lincoln replied, “If the gold fork was good enough for Buchanan, I think it’s good enough for Tabby.” (Lincoln, like most of the country, despised former President James Buchanan).

When a reporter once asked Mary if her husband had a hobby, she replied “cats.” At one point during his first term, Lincoln once said angrily, “Dixie is smarter than my whole cabinet! Furthermore, she doesn’t talk back!” At General Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters in Virginia during the siege of Petersburg in 1865, just weeks before his assassination, Lincoln was distracted by the sound of three stray kittens. Admiral David Porter wrote later that Lincoln played with them and said, “Kitties, thank God you are cats, and can’t understand this terrible strife that is going on.” Before leaving, Lincoln instructed a senior officer to “see that these poor little motherless waifs are given plenty of milk and treated kindly,” Porter wrote.

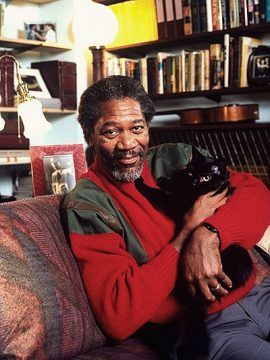

Over recent decades, it has no longer been noteworthy for men to admit their affection for cats. Curmudgeonly writers like Samuel Beckett, Charles Bukowski, Albert Camus and Truman Capote were photographed playing with their cats. The last photograph taken of Queen singer Freddie Mercury was with his ginger cat, Oscar. Then there were Walt Whitman, Theodore Roosevelt, T.S. Eliot, Steve McQueen, John Lennon, Sean Connery – the list of male cat fans grows longer and less newsworthy.

But what of those outside this warm and furry circle? The cat hater – what manner of man is this? Well, there’s a shortlist from which you can draw your conclusions. The most vicious known cat-hater was dictator Benito Mussolini, closely followed by his partner in brutality, Adolf Hitler. From an early interview, American journalist John Gunter even published a list: “The things that Mussolini hates most are Hitler, aristocrats, money, cats, and old age.” The musician Johannes Brahms despised cats so much that using a bow and arrow through an open window, he would try to kill neighbourhood cats. President Dwight Eisenhower mirrored this behaviour. When he retired to his farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, he ordered his staff to shoot any cat they saw on his property.

The little conquering emperor Napoleon Bonaparte became infamous among the generally cat-loving French for his irrational fear of cats. After he occupied Vienna, a servant heard him yelling in distress late at night. The servant found the emperor, half-dressed and drenched in sweat slashing his sword wildly through the tapestry on the bedroom walls because he thought a cat had entered the room. The Mongolian warrior and genocidal maniac Genghis Khan hated cats with vicious sadism. He once besieged a Chinese city and demanded a ransom of 1,000 cats. When they were delivered, he had the cats wrapped in oil-soaked cloth, set them alight, and threw them back into the city, which went up in flames.

“If man could be crossed with the cat, it would improve the man. But it would deteriorate the cat.” [Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.]