Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

by Akim Reinhardt

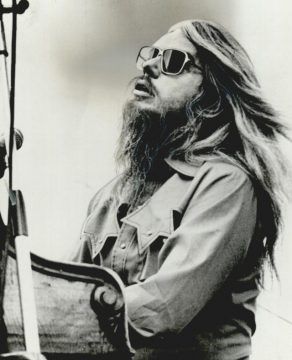

He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.

He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.

In addition to recording his own music, Leon Russell was a prolific session musician who worked with hundreds of artists over six decades. His main instrument was piano, but he played everything from guitar to xylophone. Russell was also was a songwriter who contributed to other musicians’ oeuvres. His song “This Masquerade” has been recorded by over 75 artists. “A Song For You” has been recorded by over 200. Finally, he was a record producer, a mastermind behind the glass and in front of the mixing board who oversaw and orchestrated, literally and metaphorically, the artistry of others.

The list of people Russell worked for and played with is stunningly eclectic, including: George Harrison, Willie Nelson, Ringo Starr, Doris Day, Dick Dale, Ray Charles, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Frank Sinatra, The Ventures, The Beach Boys, The Byrds, The Band, Badfinger, Bob Dylan, George Benson, Rita Coolidge, Ike and Tina, Jan and Dean, B.B. King, J.J. Cale, Glen Campbell, Gram Parsons, Joe Cocker, Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass, and The Rolling Stones.

As his own artist, Leon Russell certainly had his fans. Seven of his albums went gold. Yet during the 1970s, an era when rock n roll superstars lit up the pop culture stratosphere, he was never one of them. Only two of his singles ever cracked the Top 40, and neither of those reached the Top 10. Rather, Russell was the writer, musician, and producer whom the superstars all respected and wanted to work with. His imprint on the music industry was profound. Elton John once called him a “mentor.” Yet in the public’s eye, Leon Russell remained a relatively surreptitious figure.

Similarly, when I was growing up Russell’s music frequently wound its way through the soundscape of my parents’ apartment while very rarely taking center stage. More than half-a-dozen of the above names were part of my parents’ record collection. Russell was there even when I didn’t know it.

My parents had occasionally played a seminal live album of the era, The Concert for Bangladesh. Its six vinyl sides featured selections from the 1971 concert at Madison Square Garden that former Beatle George Harrison organized to raise money for war refugees in Bangladesh. Harrison and Bob Dylan headlined the show, which featured a Who’s Who of famous musicians. But it was Russell who served as the show’s unifying musical thread. He led the all-star band that backed both Dylan and Harrison (whose music he’d recently produced). And on side 4, he went front and center, performing a nearly ten minute medley of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Youngblood.” His performance is electric. It was a rare moment in the spotlight among more famous peers who admired and respected him.

My parents must have been at least somewhat hip to Leon Russell’s talents. They owned his 1973 album Leon Live. The truth is they rarely played it, but that didn’t mean I could completely ignore it. It too was a triple album, and its thick, bright orange, cardboard spine stuck out when flipping through their collection. Give it a listen today and you’ll hear an alarmingly tight eight-piece band (plus backup singers) wrangle a range of upbeat numbers.

As a kid, hearing but rarely seeing Leon Russell, I also thought it possible that Russell himself could hear but not see. I came to believe he might be blind.

In pictures I saw, Russell was usually wearing sunglasses. He’s hardly the only musician to regularly sport shades, of course. But for whatever reason, his dark lenses seemed so impenetrable that I just assumed he might be hiding damaged eyes. Ray Charles. George Shearing. Stevie Wonder . . . Leon Russell?

Turns out Leon Russell was not blind. It’s me, of course, who’s struggling to see.

Christ, the metaphor here is painfully obvious. As a child, I conjured a make believe blindness for Russell, and now he has returned to help guide me through my own torturous journey to see within myself.

Wow, that is truly wretched.

Fuck it. If horrible writing is the price I must pay for self revelation, then I’d rather remain a stranger to myself. Let the mystery prevail.

And in that spirit, I have no idea how, when, or why Leon Russell’s “Delta Lady” began dominating my consciousness. Like so much of life, these songs that get stuck can filter in and out, unbeckoned and unreckoned with until it’s too late, leaving me to grapple with them as best I can after the fact. To pick through my own psychological rubble in search of some insight. But if I can’t see anything amid the wreckage, then all that remains is the song.

Russell wrote “Delta Lady” for Joe Cocker, who scored a hit with it in 1969. Russell recorded his own version the following year. It’s a real jumper, rich with the gospel influences of his Oklahoma roots, an up tempo, hallelujah-style killer. No wonder then that his live renditions are even better than the studio cut. It’s one of those high flyin’ performances from 1970 that grabbed me, part of a set he recorded in front of the cameras at a California television studio. No audience. Just his band and the TV crew.

Ever the perfectionist leader, there are a couple of false starts as Russell makes sure his sprawling band is clicking on all cylinders. Then they work it through, riding the song’s driving crescendo til there’s nothing left. Everyone plays. And they they stop. There is complete silence and Russell takes a sip of water, knowing it was perfect.

But me? I can’t afford a quest for perfection. Quite the opposite. I’m delving into my own broken pieces, hoping to espy some stray shard of truth. Right now, however, I can’t see anything; I’m blind to my own inner workings. All I have is this song.

Luckily for me, “Delta Lady” never found its way into the mainlines of popular culture. It’s little known instead of chronically overplayed. So having it trapped in my noggin is not nearly as painful as it would be otherwise. And that, perhaps, is more than I deserve.

Spending a couple of weeks with “Delta Lady” has not allowed me to see myself anymore clearly, but at least it has shown me that this process can be its own reward. It has revealed nothing more than the joy of an underappreciated song carrying me along from here to there, during days when clarity is lacking and reasons are elusive.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com