by Claire Chambers

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore. Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary celebration was taking place nearby about a month later, on 12 November 2019, so I guessed their final destination was Nankana Sahib, Guru Nanak’s birthplace. The British-Indians’ presence was a reminder, if any were needed, of Punjabiyat’s close binds. To take another example, after the violence of the 1984 raid (known as Operation Blue Star) of Amritsar’s Golden Temple, some Sikhs took refuge in villages just across the border in Pakistan. It is unsurprising, then, that in Imagining Lahore, one of the best-known recent books about the ancient West Punjabi capital, Haroon Khalid takes pains amid rising Islamization to stress the region’s earlier Sikh rulers and the present-day city’s neglected gurdwaras and crumbling havelis.

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore. Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary celebration was taking place nearby about a month later, on 12 November 2019, so I guessed their final destination was Nankana Sahib, Guru Nanak’s birthplace. The British-Indians’ presence was a reminder, if any were needed, of Punjabiyat’s close binds. To take another example, after the violence of the 1984 raid (known as Operation Blue Star) of Amritsar’s Golden Temple, some Sikhs took refuge in villages just across the border in Pakistan. It is unsurprising, then, that in Imagining Lahore, one of the best-known recent books about the ancient West Punjabi capital, Haroon Khalid takes pains amid rising Islamization to stress the region’s earlier Sikh rulers and the present-day city’s neglected gurdwaras and crumbling havelis.

As ever, the trip from the airport afforded a veritable binge for the eyes. I made my way through the Beijing Underpass with its sign wishing the Pak-China Friendship a long life. Other less geopolitically-named channels evoked poets Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Waris Shah, emphasizing Lahore’s rich and proud literary culture.

Whereas I have written in a few different places about British chicken shops being an alphabet soup from AFC to ZFC, in Lahore I saw Yasir Broasts and Fri-Chicks. Passing the brightly-lit shopfront of Cakes & Bakes made my mouth water. Meanwhile, educational institutions had equally imaginative handles, including Success College and the Bluebells School.

A man, his peach shalwar kameez flapping in the wind, rode pillion on a motorbike, clutching a brace of golden-domed pots precariously as his friend accelerated. Squat, pineapple-like palm trees lined the road. A blue cement peacock emerged from the grass, its expression quizzical. A neon sign proclaimed YOUR SAFETY, OUR PROTECTION.

When I lived and taught in Peshawar during the 1990s I had taken buses everywhere, lived with the family of the headmaster I worked for, and travelled around the country during school holidays. I reflected that nowadays the security situation and my short trips fit around childcare meant I was reduced to catching glimpses of Pakistan through car windscreens.

In his book The Tourist Gaze 3.0, John Urry identifies a plethora of different ways of seeing employed by holidaymakers, which includes the ‘spectatorial gaze’. This involves a group of people being shown various sites, often through windows, which are ‘very briefly seen in passing at a glance’. Later in the book, Urry challenges the urge to travel at all, given the rise of television, the internet, and video streaming services:

The typical tourist experience is anyway to see named scenes through a frame, such as the hotel window, the car windscreen or the window of the coach. But this can now be experienced in one’s own living room, at the flick of a switch, and it can be repeated time and time again.

This trip was particularly framed for me. It was hard to get off the bubble of Forman Christian College’s campus, where I was speaking at a conference, because of the chaos primarily caused by Prince William and Duchess Kate’s visit. Lahoris I spoke to said they were happy enough to have the royals visiting, but that the lack of municipal infrastructure was creating havoc on the roads. One friend joked that if I put on a long wig I would get mistaken for Kate at least once. She began calling me ‘Duchess of  Leeds’ and sent me the gif on the left to completely finish me off. I was deceased.

Leeds’ and sent me the gif on the left to completely finish me off. I was deceased.

There was also an important urs taking place for three days at Data Darbar. I found it a little ironic that the state visit of my country’s bigwigs and the shrine I went to on my previous trip were causing gridlock and frustrating my attempts to get out and about.

On my second morning in Lahore, I was woken by a dramatic thunderstorm: a natural alarm clock that went off at 7 a.m. A version of this storm further west prevented Kate and Will’s plane from landing in Islamabad and now they had apparently returned to Lahore for a short time before jetting back to the UK. Before her abortive departure, Kate had given a speech about the importance of family in Pakistan that was being widely reported for her few words of Urdu. I had noticed something similar on my trip the previous month when I had been able to get beyond the spectatorial gaze (at least for a short while) to see relatives of many different ages out together at all hours. I enjoy that sense of togetherness, though I do worry that Kate’s comment works to marginalize those outside what Jack Halberstam would call ‘reproductive time’, such as the unmarried, homeless people, sex workers, and other ‘queer subjects’.

I had a fine time at the conference at Forman Christian College (FCC). The campus was like a university set from a Bollywood movie. Some students sported chin and septum piercings, gypsy curls, or bleached dye jobs. These seemed like people who would push against Kate’s equation of Pakistan with family values. FCC is the only place in Lahore theatre performance and science undergraduates study alongside each  other. There is much traditional respect for teachers here, with colleagues held in easy reverence by the young people they teach. I had my wrists garlanded in rose petals to watch a cultural evening of song, dance, and drama. This included a comic poet in Urdu performing ‘The Internet Generation’, as well as folksong renditions by the amazing Punjabi musician Fazal Jutt.

other. There is much traditional respect for teachers here, with colleagues held in easy reverence by the young people they teach. I had my wrists garlanded in rose petals to watch a cultural evening of song, dance, and drama. This included a comic poet in Urdu performing ‘The Internet Generation’, as well as folksong renditions by the amazing Punjabi musician Fazal Jutt.

Auspices of changing times could be seen in signs announcing zero tolerance for sexual harassment, as well as anti-corruption measures being implemented at the university. Beyond the ivory tower, an advertisement for crowd-funding on the back of an intricately decorated rickshaw was another harbinger of our incredibly shrinking world. Someone told me that Pakistan has now entered global culture, so this generation of students are the first to know their rights and things are changing fast.

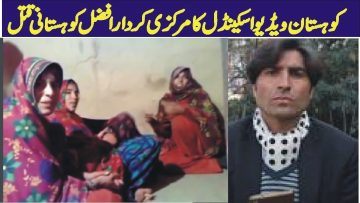

But FCC is one of the most liberal of liberal arts institutions in Pakistan, and has a special status given its Christian origins. As I watched one dance number, I couldn’t help but think of the Kohistan ‘honour’ killing case. In 2011 five women were recorded singing and clapping at a wedding as two men briefly danced, in a video that went viral on social media. All were killed for the alleged impropriety of their actions in this very conservative region near the Swat Valley. Earlier this year Afzal Kohistani, the slain men’s brother, was also shot dead in Abbottabad for his fearless whistle-blowing against jirga violence. In light of this recent murder, it is important not to exaggerate the veneer of global capital uneasily overlaying deep-grained patriarchal structures.

liberal of liberal arts institutions in Pakistan, and has a special status given its Christian origins. As I watched one dance number, I couldn’t help but think of the Kohistan ‘honour’ killing case. In 2011 five women were recorded singing and clapping at a wedding as two men briefly danced, in a video that went viral on social media. All were killed for the alleged impropriety of their actions in this very conservative region near the Swat Valley. Earlier this year Afzal Kohistani, the slain men’s brother, was also shot dead in Abbottabad for his fearless whistle-blowing against jirga violence. In light of this recent murder, it is important not to exaggerate the veneer of global capital uneasily overlaying deep-grained patriarchal structures.

As I returned home all too soon, I hurt my back lifting my suitcase onto a table to have my underwear rifled through by a judgemental woman in blue uniform at the airport. Despite this farcical precaution, I was able to pass through the metal detector and body-scanning with a litre of water.

It was a challenging journey home. The real problems were at the UK end because, although the flight took off on time, it arrived late and then my luggage took ages to arrive. An anti-Brexit march of about a million people meant there were no Heathrow Express trains, so I gambled everything on an extremely expensive taxi. I think the driver cheated me – ironically, as I had encountered no problems in Pakistan. As the metre clicked higher and higher and I could see from Google Maps I wasn’t going to make it to King’s Cross in time for my pre-booked train. (I had naively thought that three and a half hours would give me plenty of time to cross London.) In the end I asked the driver to drop me at Ladbroke Grove, thinking it might be lucky because I’m a big fan of A. J. Tracey’s song of the same name. From there I was able to take a direct Tube.  But it was a stressful race, with a painting I had bought from an exhibition in Lahore banging against my shalwar-clad legs, as I pulled along my massive suitcase wrapped in raggedy green clingfilm. Somehow managing to sprint despite all my baggage, I said a feeble ‘Help!’ to a few train guards, but they looked at me as though I was mad. I only just jumped on the train just as the doors closed.

But it was a stressful race, with a painting I had bought from an exhibition in Lahore banging against my shalwar-clad legs, as I pulled along my massive suitcase wrapped in raggedy green clingfilm. Somehow managing to sprint despite all my baggage, I said a feeble ‘Help!’ to a few train guards, but they looked at me as though I was mad. I only just jumped on the train just as the doors closed.

Despite this ordeal and the languorous nature of my spectatorial gaze on this quite restricted visit, it had all been worthwhile to see my favourite country of Pakistan. Like the Duchess of Cambridge although a little less sheltered, I would say my trip was ‘really special’.