by Joan Harvey

On this last Veterans Day, a young friend shared an essay on Facebook by veteran Rory Fanning about his wish that Veterans Day, which celebrates militarism, be changed back to Armistice Day, to celebrate those working for justice and peace. I hadn’t known that Armistice Day, which was established after WWI, had been replaced in 1954 by Veterans Day. Veterans Day, Fanning writes, “instead of looking toward a future of peace, celebrates war ‘heroes’ and encourages others to play the hero themselves. . . going off to kill and be killed in a future war—or one of our government’s current, unending wars.”

My father enlisted the first day America joined WWII, but he almost never talked about his experience. I heard about WWII mostly from my grandparents who were active in the Austrian Resistance, and in my twenties, at the urging of a Native American man I knew, I read book after book on the Holocaust. It is hard not to believe that WW II was one of the few necessary and just wars. But in this war, as in all wars, men were used senselessly, and the experience of the men fighting was often less that of achieving a clear useful goal and more of mismanaged chaos.

I’ve concurrently been reading a biography of Napoleon and listening to War and Peace. Being neither a war nor a history buff, I read descriptions of battle after battle and look at diagrams of landscapes with arrows and dots, with very little real comprehension of the topography and maneuvers and strategies implemented. But it is impossible to come away from both books without the sense of the millions of lives rapidly, brutally, and very often meaninglessly expended, the millions of young men offering themselves up to be butchered or die of disease or cold or starvation. And these descriptions recalled to my mind two great, but not much read, writers who wrote about fighting in WWII, and who gave me the strongest sense of what combat in that war was like.

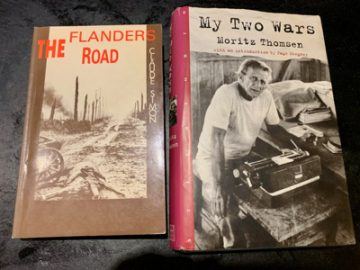

The two are very different. Claude Simon (1913-2005) was French, wrote many books, and received the Nobel prize in 1985, though in America (and apparently also in France) he’s very little read. (We are fortunate to have excellent translations of some of his books by the brilliant Richard Howard.) Moritz Thomsen (1915-1991), was American, wrote four books, and is relatively unknown. Simon’s work is thorny and difficult and reads like an extended piece of poetry; Thomsen’s is clear and emotional.

And yet there are many similarities as well. Both had family backgrounds that strongly affected their work. Simon’s ancestor was a general in the time of the French Revolution, and this is important in several of his novels. Thomsen was from an extremely wealthy (and unusually horrible) family from the Pacific Northwest; he grew up with a father who actively hated him and who vocally wished (and, when he became senile, actively believed) Thomsen dead. Both included these influences in their work. Later in life Thomsen was a farmer, and Simon was a vintner, or grape farmer, both having a strong connection to the earth. Both were stoical and ascetic. Neither, as far as I can tell, had partners when they died or had children. And both wrote from their direct experience. Thomsen wrote memoirs, and while Simon’s books have been labeled novels, he has said they were all “practically autobiographical.” Both men are brutally honest, although Thomsen is more direct and more self-effacing and seems to have suffered more post-war. And both Simon and Thomsen are astonishingly good writers who have left us with an unusually visceral and graphic sense of what it was like to have survived combat in that war.

Simon’s most famous book, The Flanders Road, is a narrative of his experience in 1940 when, at age 26, he was a member of a regiment of French cavalry who, armed with only sabers and rifles, were set (insanely) against German tanks. The regiment was almost completely massacred at the Meuse River; Simon was one of the few survivors. He was later captured by the Germans, then escaped and joined the Resistance. Thomsen was drafted in 1940, and in 1942, at age 28, was stationed in England. He was promoted to captain and was made head bombardier of a unit primarily engaged in bombing Germany. He wrote his book on his war experiences, My Two Wars, late in life, and died before it was published.

The Flanders Road is by far the more difficult book, the kind of book few had time for when it was written and, with our increasingly shorter attention spans, even fewer do today. In one sentence Simon might move from having survived a shelling in the war and finding shelter in a barren house, to being a prisoner of war, to an imagined erotic scene, to an ancestor who killed himself. It’s a disorientating and yet realistic perspective of how the mind works, moving back and forth in time among memory and imagination. One can quote only fragments of Simon’s sentences — to include one in its entirety would take a page or more. And Simon, being on the ground, was closer to the death of others than Thomsen, seeing the people around him mowed down:

. . . I didn’t know where I was or when or what was happening if I was thinking about him (beginning to rot in the sun wondering when he would begin stinking for good still brandishing his saber in the black buzzing of the flies) or about Wack head down on the slope looking at me with that ridiculous expression his mouth wide open and on which by now the flies must also have had plenty of time to gather probably the pièce de résistance so to speak since he had been dead since morning when that other saber-wielding idiot had ridden head first into that ambush . . . (The Flanders Road 89-90).

Thomsen, on the other hand, participating from up in the air, had a very different (but also not easy) perspective. His friends died when their planes, flying in formation with him, were shot down. “Without bodies for certain identification these comrades were listed as Missing in Action; they lay in us, poisonous and rotting, like indigestible food. Out there over Europe the planes with their crews simply disappeared in orange bursts of flame or, diving through clouds, faded away into an ambiguous oblivion. No blood, no last grey-faced gasping, no screams of pain or outrage” (MyTwo Wars 204).

Thomsen contrasts his role as bomber with those fighting on the ground:

Man, whose greatest, most imaginative inventions were machines for killing, was killing his brothers by the millions. Well, if it wasn’t especially fun, it wasn’t all that terrible either. Dropping bombs on people from twenty-five thousand feet—what could be cleaner, more purely and simply scenic, than that? From five miles up no bits of flesh or brains rebounded off your face, your limbs were not entwined in human guts, there were no dying screams, no cries for mercy; hell, you couldn’t even hear your bombs (MTW 274).

Thomsen was not entirely free from direct experience of carnage; once when his plane was hit, he dealt with the injured and mortally wounded on the plane with great presence of mind (though to recognize this one has to read between his extraordinarily self-effacing lines).

Both writers contrast the sheer natural beauty of everyday existence with the chaos of war. About his early days training to be a pilot, Thomsen writes, “Studying the innocence of the winding dirt roads and the white farm houses, and the small Ford tractors turning up rich dark fields of buried sod, the earth seemed so vulnerable. Impossible to believe in the reality of war and that men were gross enough to bomb and churn this holy stuff into mud and dust” (MTW 114). Simon describes the country in which a man with him is shot: “. . . ultimately it would still be the same calm and warm May evening with its green smell of grass and the slight bluish moisture that was beginning to fall on the orchards and gardens. . . ” (FR 182).

Both are critical of our whole violent capitalist system. Thomsen, son of an ultra-right John Bircher (against whom he rebelled from an early age) writes: “Even more depressing, I began to see a connection, badly hidden in the folds of the American flag, between the goofy right-wing conservatism in the fanatic wing of the super-rich Republicans and German fascism with its brutal and simplistic solutions” (MTW 6).

Simon too is critical of the wealthy: “…a species or class or race whose fathers or grandfathers or great-grandfathers or great-great-grandfathers had one day found a means, by violence, trickery or constraint exercised in a more or less legal fashion (and probably more than less, considering that right, law is always only the consecration of the state of force) of amassing the fortunes they were now spending…” (FR 114-115).

Death is the ultimate way to stop time, and being a witness to so much death has stopped or altered time for these writers. Simon’s narrative moves back and forth in time in one sentence, so that the reader is both disoriented and in a kind of eternal present that contains pre-war, war, and post war. His writing captures a kind of disintegration of existence: “. . . in the middle of this collapse of everything as if not an army but the world itself the whole world and not only in its physical reality but even in the representation the mind can make of it (but maybe it was the lack of sleep too, the fact that we had had almost no sleep at all in ten days except on horseback) was actually falling apart collapsing breaking into pieces dissolving into water into nothing. . . ” (FR 16).

Thomsen is so scarred he is marked for life by his experience. He speaks of the guilt of having survived:

We were touched with shame to be still living, to be doing the same banal things in the center of that encircling and invisible and growing pile of bodies. Why had we been unchosen? There seemed to be no way to be worthy of the dead without joining them; we were in competition with the dead who had left us, and left us filled with guilt. A passion to live. A passion to die. How could we reconcile these two emotions that kept rising in us, except in the way we did, by sinking into a kind of catatonia, an emotional hibernation that was like insanity (MTW 206-207).

Both writers describe sexual relationships with women after the war, but in both cases death overshadows the erotic and in neither case do these affairs go anywhere. The distance created by the war experience is too great. Simon’s descriptions of sex are thickly entwined with the war, so that afterwards, in bed with a woman he has long fantasized about, he is still talking to his Jewish friend who died, emphasizing this stopping of time, this return to death. The woman recognizes that she isn’t really loved for herself, and that the narrator is using sex both to evade death and to be in touch with it. Thomsen’s hasty war marriage, “a union of strangers brought together by the fear of death and annihilation,” doesn’t last. For Thomsen, “To move back into that society that could dance, sing, and rush into life with the enthusiasm of puppies seemed like a betrayal of the millions dead. The only decent response to the dead was like the response of the old who dress all in black and sit motionless for hours with vacant faces in the shade of trees— a state of perpetual mourning.

I could no longer play a part in anyone else’s drama, could not mimic tenderness” (MTW 292-293).

In the midst of battles, Simon’s narrator, sleepless and frozen and one of the few in his regiment left alive, or Thomsen, fearful and numbed after terrifying bombing raids, find that the larger purpose of the war is almost forgotten. Survival is the only thing that matters. Simon’s book in particular does not paint the bigger picture. But his Jewish friend who dies while imprisoned is a main character through the book: “. . . maybe I was still talking to him, exchanging with a little Jew dead years ago boasts gossip obscenities words sounds just to keep us awake to deceive ourselves into thinking we were awake to encourage each other. . . ” (FR 205).

Thomsen, in despair after the war, brooding on all the mistakes he made, all the blind bombing, the mass killing he has participated in, has his doubts somewhat allayed: “At least these ambivalent feelings, these slowly growing confusions, were partly put to rest as the monstrous enormity of the death camps filled the papers, as the photographs of the mass burial grounds, from which we were unable to tear our eyes, froze the blood. How could we question the necessity of fighting, of wiping out if necessary, a people so ready to be seduced into slavery by a degenerate Fascist lunatic?” (MTW 277). Then he goes on, questioning how people pretended not to know what was happening: “Millions had been murdered and they didn’t know? Was our intelligence so incompetent…?” (MTW 277).

In both authors’ writing of war, the state of being human is dismembered, reduced to an animal state, to body parts. When Thomsen is shipped back to America after the war, two hundred infantrymen are brought on board secretly at night. They are amputees that the Army does not want seen. “We met the first wave of them in the semidarkness of the hallways and were too frightened, too stunned to speak, wondering crazily, guessing—and the legs? Four hundred legs, where are they? And the arms? Where are the arms?” (MTW 281). Simon describes being a prisoner of war, packed together with others in a cattle car: “. . . in other words intertwined overlapping huddled together until we couldn’t move an arm or a leg without touching or shifting another arm or leg…that stench of bodies mingled as if were were already deader than the dead since we were capable of realizing it…” (FR 19). After a bombing run Thomsen visualizes “… the bodies of children hurtling through the air without arms, legs, faces…” (MTW 271).

Although Thomsen wrote some unpublished stories during the war, afterwards he thought he would never write about it. His whole memory of war was blocked for sixteen years. Simon writes (after a mention of the story of Circe changing men to pigs), “And so after all words are at least good for something, so that. . . he can probably convince himself that by putting them together in every possible way you can at least sometimes manage with a little luck to tell the truth” (FR 77)—the truth of his experience that men can be reduced to animals.

My friends and I always remark on how lucky we have been, unlike our fathers, to have had no experience of war firsthand, as so many did and still do. We are also lucky to have the testimony of these two astounding writers who suffered great trauma and still had the courage to show us what the unglorified, unheroic side of war is like. Unfortunately, with wars still being fought in so many places on the planet, writers must continue to find the strength and words to witness them.

Simon, Claude. The Flanders Road. New York, Riverrun Press Inc., 1985

Thomsen, Moritz. My Two Wars. Vermont, Steerforth Press, 1996