by Katie Poore

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

Shakespeare and Company apparently played host and haven to such writers and legends as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and James Joyce. In its upstairs rooms, an estimated 30,000 “Tumbleweeds” have slept on the book-lined benches that trace the rooms’ perimeters. A “Tumbleweed,” according to the Shakespeare and Company website, is a fleeting visitor, someone who, in the words of the bookstore’s founder George Whitman, “drift[s] in and out with the winds of chance,” much like the roaming thistles the word conjures. Shakespeare and Company just happens to have welcomed some of the most elite and canonized thistles the English-speaking world has known.

On my first visit to the store (yes, I went there twice), I was skeptical. It was a tourist trap, I reminded myself. Its paperbacks were marked up to the sometimes-outrageous price of 20 euros, and all because the store had harbored an impressive list of intellectual and literary powerhouses over the years. Read more »

Research by linguists

Research by linguists

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another. If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

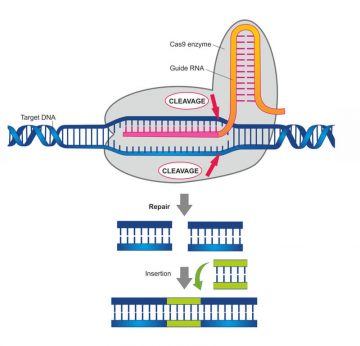

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …”

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …” He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

There should be more.

There should be more.