by Mindy Clegg

For many historians beginning their journey through graduate school, one question arises over others to prompt many sleepness nights: so what? We, as individual scholars, hope to formulate a unique choice of topics. But at times an advisor or the department might push you into a more mainstream and marketable topic, that turns heads but avoids toes. “So what?” has become shorthand for being able to show that your project helps other historians and the public understand historical processes or events in new ways. Historians tend toward a more conservative bent than our more anarchic colleagues over in English and Sociology departments or in Gender studies. It can be a steeper climb for bringing in perspectives or topics that are a bit more off the beaten path. Sometimes, a more modern historical focus or historical narratives that center on mass culture still get short-shrift, unless framed in particular ways—despite the enormous impact mass media and culture have in our world today.

The “so what?” question that historians must engage with provides the key explanation for this state of affairs. Mass and popular culture, I argue, offer a variety of ways to examine and think about history in the modern period. Understanding that impact is critical to understanding some of the key events of modern global history, from the top-down and bottom-up. Mass media and mass/popular culture have not been entirely ignored, but tend to be studied within particular contexts, such as the Cold War, to give them more legitimacy in historical studies. Often these are seen primarily in a top-down manner, for example as a vector for American empire, but there are other ways to see the spread of mass mediated popular culture. I argue here that especially in recent years, popular culture has been a location for rebuilding community in a world of capitalist individualism and for crafting new kinds of identities. How people have engaged with mass produced culture and have sought to create mass culture of their own (and control the means of production in the process) show some interesting cracks in the “society of the spectacle” facade.1 In other words, how people make connection and meaning out of the culture in which they live matters. Read more »

Research by linguists

Research by linguists

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another. If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

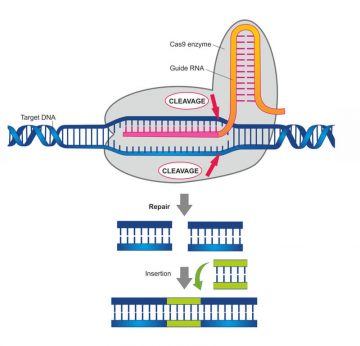

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …”

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …” He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

There should be more.

There should be more. So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss.

So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss. The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form.

The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form.