by Joshua Wilbur

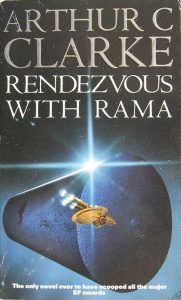

I first encountered a Big Dumb Object (“BDO”) in an underfunded school library in rural East Texas. Sitting cross-legged on the carpeted floor, I held a battered paperback just a few inches from my face, periodically turning it over to inspect the image on the book’s cover.

Rama.

I was twelve years old—“the real golden age of science-fiction”—and Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama captivated my imagination. The novel’s premise is simple: an alien starship, a massive cylinder of unknown origin and construction, has entered the solar system, and a crew of scientists must investigate. Thin on plot (and even thinner on characterization), Rama lingers in my memory not for what’s hidden within the vessel but for what’s kindled from without, from the mere suggestion of a colossus come from the stars. It stirred in me what sci-fi critics have called the “sense of wonder,” a feeling of awe that courses through the heart of the genre.

Nothing better epitomizes this sense of wonder than “Big Dumb Objects,” a term coined by Roz Kaveney and lovingly adopted by fans of the science fiction genre. BDOs, as you’ll have guessed, are really big, dumb in the old sense of “mute, silent, refraining from speaking,” and usually serve as a focal point for narrative action. Mysterious thing is discovered; mysterious thing is explored. In a Weird Things column for The Guardian, Damien Walter defines the BDO:

“ … the Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a unique selling point of the sci-fi genre. It can be a broad term – usually, they’re alien architectures, ranging from the man-sized to the planetary. BDOs either look extreme or unusual, and can often do extreme or unusual things: everything from lurking on a horizon to creating worlds. Usually, BDOs are plonked into plots to awe us with their majesty and mystery – really, they’re science fiction’s equivalent of a MacGuffin.”

BDOs participate in J.J. Abrams’ often maligned “mystery box” approach to storytelling. For Abrams—the creative force behind Lost, Cloverfield, Super 8, and the Star Trek and Star Wars reboots—stories are mystery boxes, containers of “infinite possibility and [the] sense of potential.” Like a Kinder Surprise Egg (a chocolate treat once amusingly deconstructed by Slavoj Zizek) or the “loot boxes” now so prevalent in videogames, the feeling of anticipation far surpasses the eventual discovery of what’s inside, which explains why Abrams’ conclusions sometimes fall flat. The riddle is better than its answer.

Big Dumb Objects are physical promises, harbingers of something more. And their physicality comes in several geometric forms. There are hulking cylinders: Clarke’s Rama, the whale-seeking probe of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, and the hollowed-out asteroids of Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312 and Greg Bear’s Eon. There are foreboding spheres: Michael Crichton’s Sphere, the Death Star (“That’s no moon!”), and the Dyson Sphere, a hypothetical megastructure surrounding a star and sapping its energy, first imagined by Olaf Stapledon in Starmaker and later included in a number of space opera novels. There are gigantic rings (in Stargate, Ringworld, Halo) and mysterious cubes (in Star Trek, Cube, even Fortnite).

In all mixed shapes and monstrous sizes, BDOs populate the sci-fi landscape. They tantalize us with the Lovecraftian unknown, with hints of a long-lost creator or unfathomable motivating force. The truth is in there.

This notion of a hidden, higher truth is what attracted me to BDO stories as an adolescent. Rama withheld more enticing secrets than my town’s cattle-filled pastures, piney woods, and red-brick churches. In Science Fiction in the 20th Century, Edward James writes that “[science fiction] can create a rival sense of wonder, which acts almost as a replacement religion: a religion for those deprived of all traditional certainties in the wake of Darwin, Einstein, Plank, Godel, and Heisenberg.” In lieu of the gods, Big Dumb Objects point to a deeper meaning concealed somewhere within the universe itself, a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

In the realm of fiction, BDOs satisfy our basic desire for mystery. But what about the real world? If I were to go looking for a Big Dumb Object, could I find one?

Nature, of course, offers no shortage of giant, unspeaking stuff. Our planet boasts volcanic mountains, redwood trees, and tabular icebergs. Seeing such things affects us deeply. Like the speaker of Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey, we encounter “beauteous forms” and experience “a sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused […] a motion and a spirit, that impels all thinking things, all objects of all thought, and rolls through all things.” We’ve all felt this Romantic rush at some time or another. But, as a rule, BDOs imply design. A mountain is not a Big Dumb Object (unless it’s an artificial mountain, secretly housing an imprisoned creature or a terrible weapon or a reclusive tribe). A mountain—however inspiring it may be—is an aimless mass of rock and earth. No doubt, there is mystery in the objects of the natural world (especially if one’s doors of perception are opened wide), but no apparent design.

What about man-made objects? What of 747s, skyscrapers, oil tankers, religious statues, megamalls, and nuclear reactors? In cities, we are dwarfed by immense structures made of brick, concrete, and steel. I sometimes ask myself how do they build these things, how is it possible to construct something so tall? But then I know that there’s really no secret to it: the highest high-rise is born of well-trained architects, intricate blueprints, an abundance of materials, plenty of workers, and lots of time. And the purpose of most structures is also obvious. Buildings hold people, just as planes fly and boats float. There is design but no mystery.

If I’m to discover a real life Big Dumb Object, then I’ll need to find something that conveys both purpose and secrecy, which is no easy task. The Pyramids come to mind, but they’ve been well-studied by now, confirmed as tombs, rendered historical. There are the Pictish stones in Scotland, which are covered in strange symbols and reminiscent of the monolith in Arthur C. Clarke’s other great BDO story, 2001: A Space Odyssey. But, again, my “sensawunda” is stifled by the knowledge that the passage of time has obscured what in all likelihood is a perfectly logical explanation for their existence. The same goes for ancient temples, old artifacts, and abandoned buildings. “The past is a foreign country” (and endlessly fascinating for that reason), but a true BDO strikes us in the present and pulls our imaginations into the future.

I’ve already mentioned skyscrapers as fairly obvious objects—transparent symbols of financial expansion and office culture—but there is a strange exception jutting from lower Manhattan’s TriBeCa neighborhood. It is a faceless block, a building without windows, an extreme example of the Brutalist style of architecture that dominated during the mid-twentieth-century. The AT&T Long Lines Building at 33 Thomas Street, located between Thomas and Worth Streets, is a forbidding structure, and I can’t see it without imagining what’s inside and wondering what deep forces operate outside of my awareness. In other words, it’s a Big Dumb Object.

Completed in 1974, the AT&T Building at 33 Thomas has ostensibly served as a telecommunications hub for more than forty years. The concrete, windowless structure is far from usual, however: it was built to withstand a nuclear blast. 33 Thomas originally contained telephone switches and coordinated phone calls, but today it houses one of the world’s most secure data centers and maintains mysterious ties to the NSA. A 2016 report from The Intercept tells the story of the “NSA’s Spy Hub in New York, Hidden in Plain Sight,” codenamed TITANPOINTE. The article notes:

“It is not uncommon to keep the public in the dark about a site containing vital telecommunications equipment. But 33 Thomas Street is different: An investigation by The Intercept indicates that the skyscraper is more than a mere nerve center for long-distance phone calls. It also appears to be one of the most important National Security Agency surveillance sites on U.S. soil — a covert monitoring hub that is used to tap into phone calls, faxes, and internet data.”

The report (which is well worth reading) goes on to include details from whistleblower Edward Snowden’s released documents—as well as “architectural plans, public records, and interviews with former AT&T employees”—in making the case that 33 Thomas is first and foremost a surveillance facility. The building certainly looks the part. But the truth is that we, the general public, cannot know for sure. 33 Thomas is a giant question mark in the middle of downtown Manhattan. And in spite of whatever insidious actors might reside within, I can’t help but appreciate the structure, its looming presence a constant reminder that there’s still uncharted territory in our world.

And far beyond. Outer space, as Star Trek tells us, is the “final frontier.” For months, I’ve followed the observations of and speculations about ʻOumuamua, the first interstellar object detected passing through our solar system. The object is peculiar for several reasons: its unclear origins, its elongated shape, its unusual shininess. Harvard researchers have speculated that ‘Oumuamua may be an artificial object, a light sail created by an alien civilization. It’s a tantalizing suggestion, but, again, we cannot know without more information. ‘Oumuamua is a potential BDO on the move, tumbling through the solar system at more than twenty-six kilometers per second and frustrating efforts to learn more about the object. And yet, with more than one hundred billion stars in our Milky Way Galaxy alone, there is endless possibility for more. For now, we wait and dream.

In the meantime, I’ll continue my search for BDOs closer to home. If nothing turns up, then I can always adjust my manner of looking and adopt a beginner’s mind. The world teems with Big Dumb Objects for young children, for example, who experience everything for the first time. Childhood proves that finding mystery in the mundane is always a matter of perception. This was a fundamental truth for the poet William Blake, who, in a letter to Reverend John Trussler, suggests a possible path forward in our pursuit of higher meaning, as we hold out hope that big answers exist underneath the surface of things:

“[…] I know that this world is a world of imagination and vision. I see every thing I paint in this world, but everybody does not see alike. To the eyes of a miser a guinea is far more beautiful than the Sun, and a bag worn with the use of money has more beautiful proportions than a vine filled with grapes. The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity, and by these I shall not regulate my proportions; and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself. As a man is, so he sees.”