by Joseph Shieber

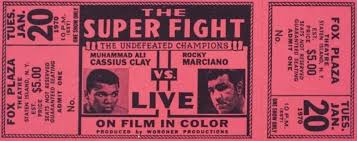

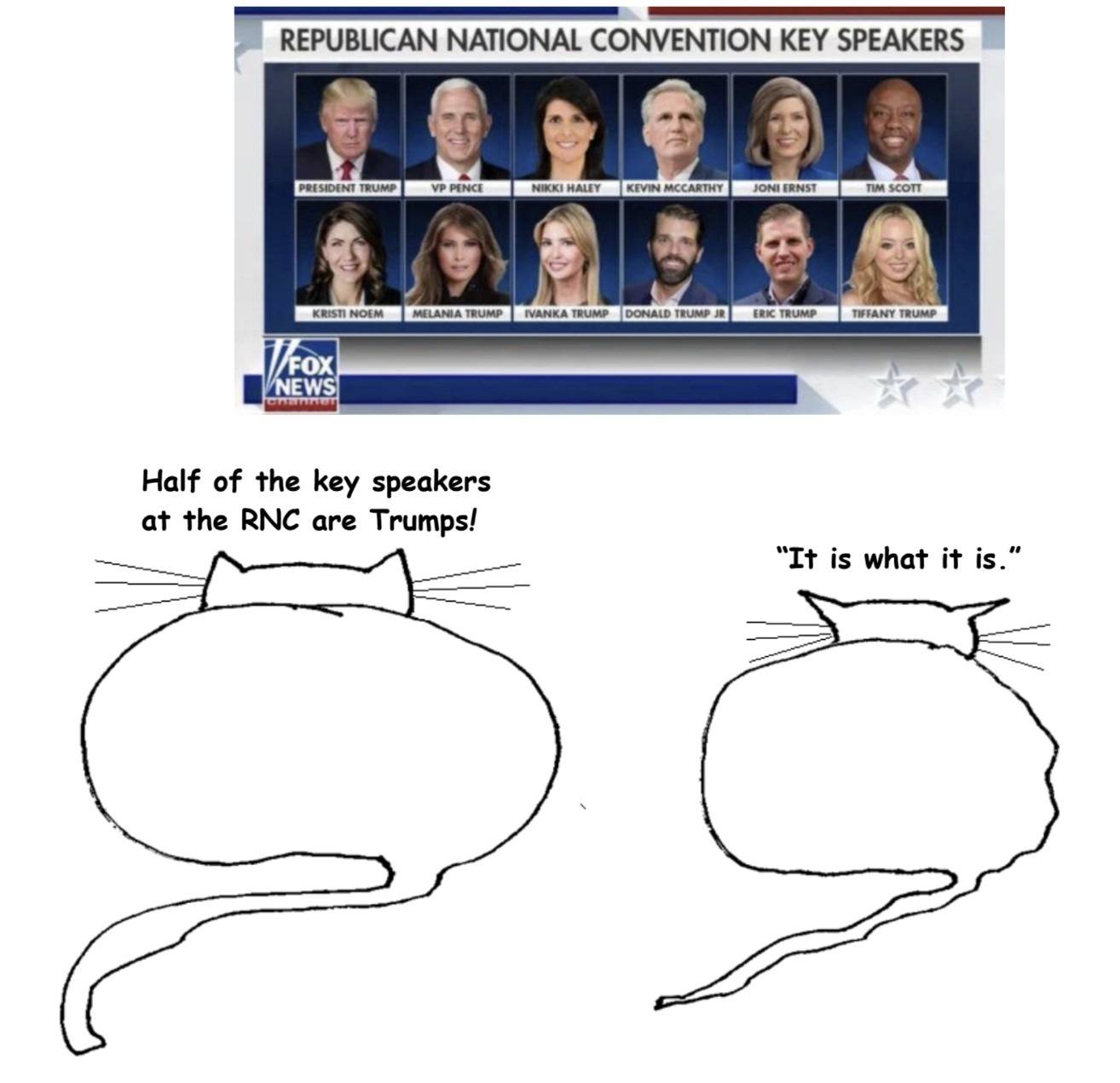

As the quadrennial presidential and vice presidential debate season nears once more, we’ll soon see opinion pieces reminding us that debates have at most a very slight impact on the outcome of presidential contests.

Typically, the writers of those pieces frame their discussion as a warning not to place too much importance on the debates. I want to make a different argument about the presidential and vice presidential debates: we would do better to get rid of them altogether.

The crux of my argument against the presidential and vice presidential debates is that they don’t serve any of the audiences who might tune into them.

Those who follow politics already know the candidates’ track records and plans, so — as anyone familiar with the literature on the informativeness of job interviews can tell you — the debate doesn’t provide any salient information, just noise.

And what about those who aren’t informed consumers of political information? Focusing on the effect of debates on uninformed or undecided voters arguably distorts the discussion of the relative merits of the presidential candidates in ways that damage substantive coverage of political issues.

This is because, if they’re even watching the debates at all, uninformed or undecided voters are almost certainly focused on the wrong signals. Appreciating who refrained from perspiring, who wasn’t sighing annoyingly, or who had the snappiest one-line rebuttal doesn’t actually tell voters anything about who would promote policies that best represent those voters’ — and the country’s — interests.

And for the media, debates just provide another excuse to focus on horse race and style over track record and substance. Read more »

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.