by Richard Farr

On a road trip once, navigating a deliberately eccentric route from Houston to El Paso, I was enjoying the emptiness — rocks, ravines, three other vehicles per hour — when I spotted something alien and odd. On a ridge to the northwest two monstrous hard-boiled eggs sat fresh-peeled and gleaming. It might have been a witty installation by Claes Oldenberg. I stood by the car in the brick-oven heat and peered at my paper map.

The ridge was part of the Davis Mountains; the eggs were the U of T’s MacDonald Observatory. I pulled into the parking lot just as a tour group emerged from a purple van. Their bumper sticker said ASTRONOMERS DO IT ALL NIGHT. They looked like extras from a movie about the glory days of the Apollo program. One of the men actually had a buzz cut, a pocket protector, and eyeglasses mended with tape; it might almost have been cosplay, but wasn’t.

One of the resident gazers gave us an al fresco lecture. The astro-tourists didn’t ask him which end of the telescope was which. They asked about precession, and how to collimate the mirror in a large Dobsonian, and how to get the best out of deep-sky subjects with hydrogen-alpha filtering. One of them mentioned the Veil Nebula; others nodded sagely and proffered advice on best practices for capturing the Rosette, the Tarantula, the Horsehead. They discussed how to star-hop from M-this to NGC-that as if comparing routes to Albuquerque. Our guide warmed to them, digging deeper into his expertise, tossing off references to Fraunhofer lines and Cepheid variables.

It was unexpected and strangely exhilarating to find this intense, quirky, intelligent inquiry, naïve inquisitiveness in the noblest sense, in the emptiest reaches of Texas. In universities, in the urban wilderness, you sometimes meet people like this. Just for the jazz of it they’re retranslating Hölderlin’s poetry or trying to prove Goldbach’s conjecture or performing Palestrina on the original instruments.

They’re drunk with fascination, fools for love, in mitochondrial genetics, quantum cryptography, or early Restoration drama. People like that seem to have concerns so wholly unlike those of the culture around them that they remind me of the Ionian monks on their windswept nub of rock, who held a tradition of the mind up above the waterline while the Dark Ages engulfed everything around them. Curiosity can be such a sweet disease! The people from the purple van, with their quirky zeal for the dark abyss, seemed less like humans than like visitors from a wiser, maturer world, at once more ardent and more placid.

As a small boy growing up in England I watched Patrick Moore’s The Sky at Night every week on the telly. His clothes were deranged, his eyebrows looked like rioting corkscrews, and he projected an enthusiasm that made nonsense of the idea that you could possibly want to waste your time with anything other than astronomy. Because of him I got a small spotting scope for my twelfth birthday. We had a rickety antique tripod acquired from my grandfather. I stood in the upstairs corridor with the window open, trying to stop the moon bouncing in and out of the field of view like a silvered yoyo. We must have done it eventually because I saw the rims of craters along the terminator. We even located the smudge that was Andromeda.

This was before pocket calculators. But I was a boy on a mission with scratch paper and time to kill. “Mummy listen. The Andromeda galaxy is even larger than the Milky Way and it’s two and a half million light years away. That’s nine hundred and eleven million light days. Which is twenty two billion light hours. Which is one point three trillion light minutes. Which is seventy eight trillion light seconds.”

“That’s a lot, darling.”

“It means Andromeda is sixty trillion times as far away as the moon.”

“Well!”

“Sixty trillion. That’s six with thirteen zeroes after it.”

“Goodness.”

“Guess how long it would take the Apollo astronauts to get there.”

“I don’t know.”

“Guess.”

“A long time.”

“Go on.”

“Three weeks.”

“You’re not trying.”

“Three months.”

I roll my eyes. I’m amazed that she’s not grasping how amazed she’s meant to be.

“Four hundred and ninety seven billion years.”

“What a lot of clean underwear they would have to take.”

The memory of these calculations, and of Patrick Moore’s commitment, makes me ashamed to admit that astronomy did not turn into a lifelong passion. Soon I drifted back to my plastic Spitfires and Messerschmitts, stealing cigarettes from the local shop, getting into pubs under age.

And the deep addiction: girls. You’re getting on with life as best you can, actually getting important calculations done using only the stub of a pencil, then one day you wake up and discover that someone has injected pepper into your blood. You can no longer concentrate for five consecutive minutes on anything. The stars didn’t have a chance. Astronomy disappeared from my horizon and I didn’t think about it again for years.

But that night on a camping mat in the Texas wilderness my childhood enthusiasm came back to me. Looking down into the bottomless void, I was a bat hanging upside down in the belfry of the solar system. I stared and stared, unable to get enough.

I love what I can name, and I love the names: Cassiopeia, Rigel, Mizar, Crux Australis, Perseus, Epsilon Eridani, Tau Ceti, Triangulum. They are the poetry of the sky we have made. But there are parts of the sky I can’t name, and I like that too. Those regions aren’t biddable. They don’t fall into patterns at the eye’s command. In those parts there is nothing but raw flung creation. Looking there, you can imagine what it’s like to watch a firework without knowing what a firework is, seeing only the beauty and not the art. And this firework is everything.

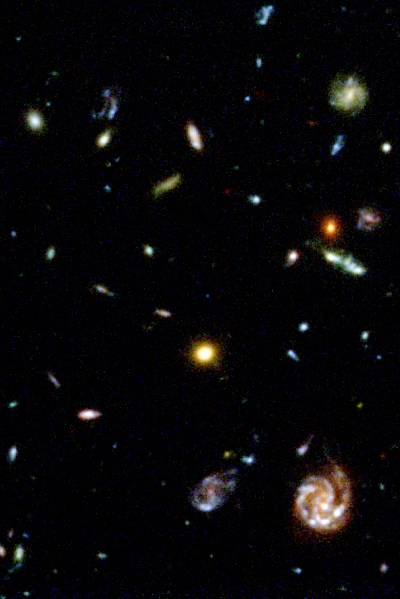

Astronomy is full of gorgeous beasts: the great star cluster M13 in Hercules; Saturn and its satellites; gravitationally-lensed quasars; the star hatcheries of the Orion Nebula. But astronomy is not flower appreciation. There’s a spiritual as well as a bodily coldness in the business of deep space. No photograph has ever appealed to me and appalled me and fascinated me quite so much as the original Hubble Deep Field North. It reveals what’s hidden in a tiny cinder of sky near the twin stars Alcor and Mizar in Ursa Major: at first glance, nothing more than a smeared field of yet more stars. But almost every smudge, speck, and tendril of light — scattered over the dark like steel swarf glinting up from the floor under a lathe — is a galaxy.

The shift in scale is sudden, massive, unforgiving, from something “unimaginably big,” as people like to say of Alaska or the Pacific, to something so many orders of magnitude vaster that you couldn’t fit the zeroes into a bowl of soup. Immersed in those depths you know for certain, Fermi’s paradox be damned, that there are civilizations, entire worlds, that are lost to us, unknowable; that will leaf and flower and fall – and, a few billion years later, be roasted like chestnuts in the embers of a dying giant – without human eyes ever having witnessed them.

It’s like going into a library and knowing there is too much to be known. Or seeing a foreign crowd on the news and knowing that these people can’t be known. You want to scream and rage and rattle the bars of your own limitation. Why in God’s name so much, just beyond the tips of our fingernails? “Had we but world enough, and time.” That we don’t can sometimes seem unbearable.

I’m standing with my wife on our front step in the cold Pacific Northwest, surprised by the beauty and clarity of Aldebaran, pointing and craning, wanting (not for the first time) to find a way to make her share my awe.

She does not.

“There. And look, above the trees: that one’s Arcturus. You can always find Arcturus by – ”

“Yes, I know, you’ve told me before. Can we go inside now? I’m freezing my butt off out here, and Arcturus is several light years too far away to warm it up.”

“Definitely too far away. More than thirty-five light years. Though that’s right next door in galactic terms and – ”

She shoves me through the front door into the warmth. My wedding ring glints in the light. According to one of science’s most beautiful stories — Fred Hoyle’s theory of stellar nucleosynthesis — its atoms were anvilled into being long before the Earth was formed, when two neutron stars embraced.