by Joseph Shieber

The philosophical world has recently been abuzz about Susanne Bobzien’s argument that Gottlob Frege — often taken to be one of the founding figures of what became 20th century analytic philosophy — plagiarized many of his logical positions from the Stoics.

Bobzien’s charge isn’t merely idle speculation. In her paper, descriptively titled “Frege Plagiarized the Stoics”, Bobzien brings the receipts. In painstaking detail, she demonstrates the ways in which many of Frege’s signature views — previously often thought to have been radical innovations in logic and philosophy of language — mirror almost verbatim the language of the chapter on Stoic logic in Carl Prantl’s influential Geschichte der Logik im Abendland (History of Logic in the West).

In painstaking detail, Bobzien lays out her case that not only was Frege strongly influenced by Stoic ideas, but also that he copied those ideas from one source, Prantl:

First, it is vastly more likely that Frege obtained his knowledge of Stoic logic from one text, rather than from browsing through the dozens of Greek and Latin works with testimonies on Stoic logic that Prantl brings together. (Of the hundreds of Stoic logical works, not one has survived in its entirety and we are almost completely dependent on later ancient sources.) Second, virtually all parallels between Stoics and Frege are present in Prantl, and some important elements of Stoic logic without parallels in Frege are missing in Prantl. … Third, there are several misunderstandings or distortions of Stoic logic in Prantl which do have parallels in Frege.” (pp. 8-9 of Bobzien’s paper linked above)

In one sense, it’s hard to exaggerate the significance of Bobzien’s findings. In the words of Ray Monk, the acclaimed biographer of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell, “it is Frege who [of the triumvirate of Frege-Russell-Wittgenstein] is—100 years on from his retirement—held in the greatest esteem by the philosophers of today.” Read more »

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

The disappointing new film

The disappointing new film  Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

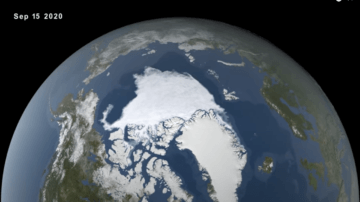

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us. In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

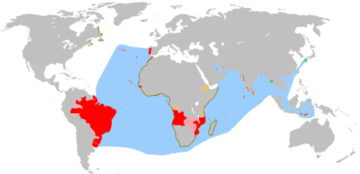

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?” The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (