by Maniza Naqvi

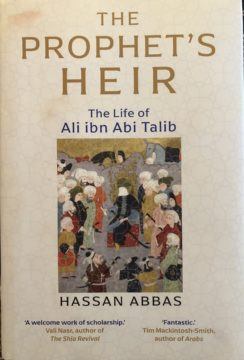

Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.

Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.

For many of us this poetic verse feels as though it were a statement of fact:

Ghalib Nadeem e dost sey ati hey bo e dost

Mashgul e Haq hon bandagee-ey boo Turab mein

From the fragrance of the divine friend comes the scent of the friend

I am immersed in search of Truth in my devotion to Ali.

Who are these friends and what is that scent? The Message of Islam is revealed onto the Prophet Mohammad at age 40. Alongside Mohammad is his unwavering constant dearest companion—one of the first to accept Islam— and born in the Kaaba, his 9 year old kid cousin Ali ibn Talib whose mother and father raised Mohammad as their own child, long before Ali was born. For Mohammad, peace be upon him, Ali is the loyal adoring kid brother, the protege, and in age difference the son. The Prophet chooses Ali, as his example of the path of Islam the Shariah—-he recognizes him and entrusts Ali as the exemplary embodiment of what Islam means. The Prophet is the Messenger and his closest companion Ali, who pledged his loyalty to Allah and his Prophet and his message is the essence of Islam, he is the Shariah—- lived. The Prophet peace be upon him proclaimed this essence as:

Man Kunto Maula fa hazaa Ali-un Maula

For whom ever I am Leader and Teacher, Ali is his Leader and teacher too.

For most of us gathered here today this essence translates to exquisite beauty lit by splendor achieved through love and loss and longing and struggle. This beauty moves us inexplicably, —moves us towards justice and generosity and kindness. Read more »

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020.

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020. “Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136).

“Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136). On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary. Podcast time!

Podcast time!

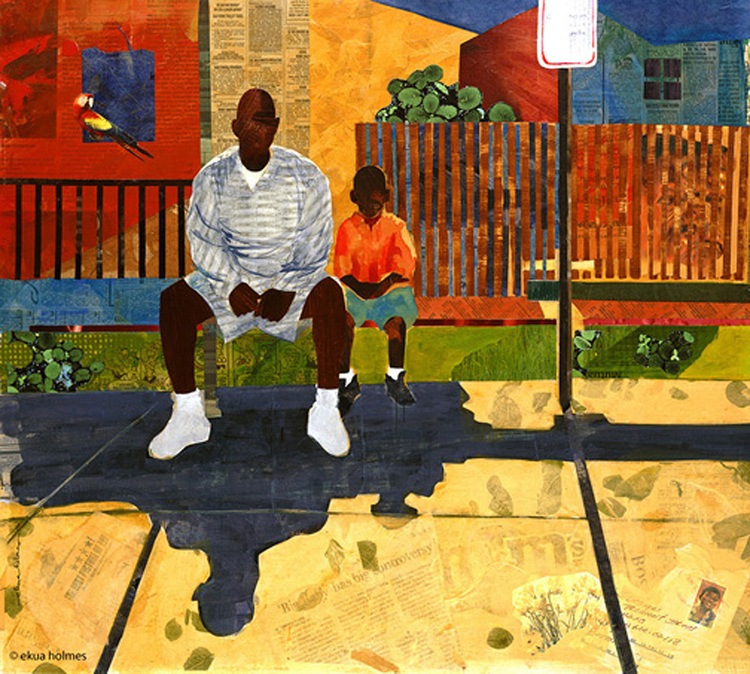

Ekua Holmes. There’s No Place Like Home.

Ekua Holmes. There’s No Place Like Home.