by David Oates

We are always looking for the book it is necessary to read next. —Saul Bellow

That quote hangs over my writing desk. Its purpose is to remind me of the urgency of writing. Not the correctness of writing, not its sentiment or fashionability or mild amusement: its urgency. Bellow wants what I want – what every reader wants: the book that is necessary and of the moment, now.

It’s what drives me as a writer. As a reader. And as a small-press publisher.

In the marketplace of books, it can be hard to find that next, necessary book. I keep a list of what to read next – lots of people do. But what is offered to me? Mostly big books from big names, published in editions up into the millions of copies (Michelle Obama’s initial print run for Becoming was 3.4 million, increased to 4.3 million because of demand). The big publishers want sure-fire bestsellers. . . but are these really the necessary books? The “Big Six” publishers who dominate the English-speaking book world have consolidated yet again – it’s the “Big Five” now – and they want a guaranteed return on investment. Until authors can guarantee sales – until they are already in some way famous – why would Penguin Random House give them a contract?

Profit is their necessity, but it’s not mine. I want what is of the heart and of the moment, not merely what is salable.

This disconnect is what has brought small publishers to the fore. They take chances. They can afford to look for excellence, freshness, that je ne sais quoi. I think they follow trends that no trends that aren’t trends yet. And they look above all for urgency. They give writers their first and second books. They edit, sometimes fiercely. They create for writers time and space to grow.

In the economy of creativity, this is how it works now. It’s the little presses who are performing these crucial services. While the big guys make money.

It is easy to bemoan the difficult path of the creative soul. How we miss those legendary nurturing editors of yore! But I also want to ask – was it ever really that easy? I am imagining that for every F. Scott Fitzgerald or Ernest Hemingway discovered by an avuncular editor of astounding patience, there were hundreds of comparable talent whom we’ve never heard of. The mute unsung Miltons of their day.

The small presses are fulfilling functions that once were available at the big houses for only a few lucky writers! And rather than thinking ourselves blue with nostalgia, let’s acknowledge that in today’s publishing landscape, almost anything is possible. Little books from unknown authors break into print every day. And among them are many that are wise, clever . . . and urgent. The good ones are finding their way despite the Big Five.

* * *

Like a golden-age myth, the memory of famed Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins haunts American writers. In 1918, twenty-one year-old Fitzgerald had managed to get the manuscript of his novel The Romantic Egoist into Perkins’ hands . . . only to be rejected with extreme gentleness and the alluring phrase “we should welcome a chance to reconsider its publication.” Of course the author worked on it like a hive of bees and in six weeks sent a retitled, rewritten version back to Perkins. . . to be rejected for a second time. But still Perkins saw something in it and offered the now-famous advice of changing the narrative point of view to third person.

Like a golden-age myth, the memory of famed Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins haunts American writers. In 1918, twenty-one year-old Fitzgerald had managed to get the manuscript of his novel The Romantic Egoist into Perkins’ hands . . . only to be rejected with extreme gentleness and the alluring phrase “we should welcome a chance to reconsider its publication.” Of course the author worked on it like a hive of bees and in six weeks sent a retitled, rewritten version back to Perkins. . . to be rejected for a second time. But still Perkins saw something in it and offered the now-famous advice of changing the narrative point of view to third person.

Kathleen Dixon Donnelly at the American Writers Museum tells what happened next:

“By the time the finished manuscript arrived on Perkins’ desk in September 1919, the title had changed to This Side of Paradise and Perkins knew he had something worth fighting for.

“Perkins’ legendary meeting with the editorial board introduced the themes which continued throughout his career at Scribner’s. When the book was rejected by the other editors for the third time, Perkins said, “My feeling is that a publisher’s first allegiance is to talent. And if we aren’t going to publish a talent like this, it is a very serious thing. . . . If we’re going to turn down the likes of Fitzgerald, I will lose all interest in publishing books.”

The debut novel went on to become a sensation. Fitzgerald’s jazz-age tale of a mad new generation had caught the postwar mood exactly. Perkins would edit and mentor luminaries such as Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, John Jones (From Here to Eternity), and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. He brought his writers along with kindness and insight; urged them (sometimes with great specificity) to rewrite; acted as mentor and defender and advisor and friend. This is the kind of editor we all revere and miss, from lo even these many generations later.

But let me introduce a note of realism. How exactly did green young Fitzgerald manage to get his manuscript to penetrate so deep into Scribner’s in the first place? It was because of someone he knew. He had attended the Newman School, a prep academy in New Jersey. His English teacher had been one Father Sigourney Fay who happened to be friends with Scribner’s author and Irish diplomat, Sir Shane Leslie. He persuaded Leslie to forward the manuscript to Scribner’s, and away it went.

As a West-coast writer with nary a famous friend, I can tell you I’ve heard far too many stories of East-coast preppies (and even known a few) whose careers run forward on mysteriously greased skids. That part of the story hasn’t changed, 1919 or 2019. And for all those talented writers in St Paul and Bakersfield and Amarillo whose manuscripts are not welcomed and massaged and revised by people who know the right people . . . let us temper our golden-age nostalgia. Then and now, high-powered getting-ahead has as much to do with who you know as what talent you might be bringing. It’s the way the world has always worked.

* * *

Yet there are evidently no more Perkins-like editors welcoming non-bestselling manuscripts anywhere in the Anglophone world of big publishing.

Bigness has overtaken publishing, and bigness must be fed continually. The behemoth of publishing is the newly amalgamated Penguin Random House, which according to New York Times reporter Alexandra Alter is now as big as the rest of the Big Five combined (Hachette, Harper Collins, Simon and Schuster, Macmillan).

“As publishing becomes even more of a winner-take-all business, Penguin Random House’s dominance represents the culmination of decades-long trends that have made the industry more profit focused, consolidated, undifferentiated and averse to risk.

“Like Hollywood, which pours resources into universe-scale superhero franchises that are nearly guaranteed to get an audience, publishing has become increasingly reliant on blockbusters – a development that has left beginner and midlist authors struggling. Mass-market retailers like Target, Walmart and Costco . . . buy books that are surefire hits, and often wait for an unproven author to hit the best-seller list before they even order copies.”

“The impact on literary culture is more homogenization,” says independent-press co-publisher Dennis Johnson of Melville House. Bigness wants one thing: gigantic hits. It doesn’t want fresh books – even brilliant ones – if they will need a year or more to find their audiences. So mostwriters, good bad and excellent, are ruled out before their letters of inquiry are ever trash-binned at the big houses.

Who will “spot breakout literary talent” when it appears? No one at the Big Five.

Which leaves, obviously, a niche waiting to be filled: an opportunity that has led to the flowering of small-press and independent publishers.

* * *

I write to praise the small presses. In the literary ecosystem, they are the photosynthesizers and unobtrusive bugs, the quiet fields of ripening grass and the silent throngs of unseen life. What they do is allow a writer hope – and the fellowship of the love of books and beautiful courageous expression – and feedback on what works or what must be revised. To look into this tangled bank is to see brilliance as well as oddity. It is to be filled with hope and the desire to order even more books for one’s already sagging shelves.

Consider small presses like Dorothy, Rose Metal Press, Black Lawrence Press, Ugly Duckling, Yesyes, and Spurl Editions. These are some publishers listed by Brent Cunningham of Small Press Distribution (SPD). He’s one of the sharpest and most generous professionals I’ve met in my decades in the writing life. He writes me back about these indies: “They each have a book or three they recently managed to get out there pretty widely, but are still serving all those critical small press functions you mention (many, yes, formerly the domain of bigger presses. . .).”

SPD is the distributor for about 400 academic and small presses (including mine), the critical link for getting books into bookstores and the hands of readers. Its mission:

“SPD is the only wholesaler in the country dedicated exclusively to independently published literature. We take risks on exciting new writers, enabling their work to develop an audience and gain recognition in the marketplace.”

Lee Wind of the Independent Book Publishers Association observes, “Something we see at IBPA is that indies are often mission-driven.” His list of favorite examples includes Just Us Books, Patagonia Books (“the publishing part of the clothing company that’s all about their sports/outdoors/environmental mission”) Elva Resa Publishing (“books for military families”), She Writes Press, and poetry stalwart Red Hen Press.

* * *

I became a small publisher in 2008-2009. It’s an origin story grounded in frustration, that strangled-and-ignored feeling that is so familiar to most of us in the writing life. Though I had a nice handful of books in print, mostly from university presses, I had a new project for which I could get no traction at all. It was hot and of the moment: a book of essays on the experience of being a “citizen of the regime” of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney—the regime of state propaganda (the orchestrated lies leading to the Iraq War), the regime of torture and almost fantastically botched military adventurism.

Probably our recent experience with the mendacious quasi-fascist president has somewhat softened memories of that previous round.

But for me it was scarring, an alarm-bell in the night, and I felt compelled to get into print immediately – with (yes) urgency. Some of its pieces had appeared in periodicals, but slogging the book manuscript through years-long rejection processes promised me nothing but more frustration. Bush was leaving office and I felt I must get the work in front of readers.

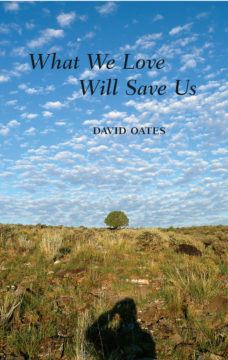

I scrambled. I founded Kelson Books. And I got What We Love Will Save Us into print before the blood had dried on the Bush/Cheney nightmare.

I scrambled. I founded Kelson Books. And I got What We Love Will Save Us into print before the blood had dried on the Bush/Cheney nightmare.

What shocks me now is how relevant that title essay still seems. The struggle for moral and spiritual balance, under the provocations of high-level evildoing – these are challenges as sharp-edged now as ever.

“We are all, too much of the time, captives of the wreck and the mistake. Can’t take our eyes off it, can’t stop thinking about it, can’t stop picking that scab. Defined by what we refuse, we slide into our merely negative identity.

“But it’s not enough, is it. Is our nation adrift, hijacked by mountebanks and neocons and thugs? It is not enough to hate them. We must remember what we love. Time spent saying no is, at some point, time robbed from the yes that must follow. A long time ago I read Jesus’ words “Do not resist evil” and wondered what in the world he could have meant. Maybe this: We must stand on what we love – live it, be it and bring it. And not waste time in the other direction, preaching up devil and denunciation.”

Though the triggering catastrophe is now far back in the rear-view mirror, every year I still get a few surprise emails thanking me for this little essay.

* * *

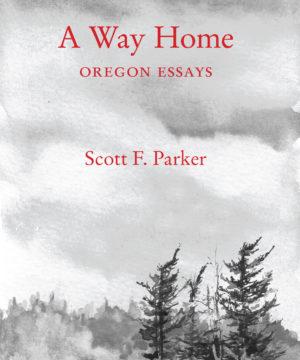

At Kelson Books in the years since, I have had the opportunity to fulfill some of that Max-Perkins role, helping talented writers who have come to our house with projects not quite shapely yet, obscured in some obscure way and not ready for print, yet at base worthy and exciting. I’ll give one example, the beautiful book we recently published called A Way Home: Oregon Essays, by Scott F. Parker.

At Kelson Books in the years since, I have had the opportunity to fulfill some of that Max-Perkins role, helping talented writers who have come to our house with projects not quite shapely yet, obscured in some obscure way and not ready for print, yet at base worthy and exciting. I’ll give one example, the beautiful book we recently published called A Way Home: Oregon Essays, by Scott F. Parker.

Parker was already an experienced writer when he contacted me about his manuscript. When I read it, I was excited: here was immediacy, brains, a touching theme. He took his reader, step by step, into classic Oregon terrains and made them new and fresh. It was like remembering yesterday’s hike, full of sweat and unexpected vistas. Yet . . . like a lot of brainy writers, he sometimes got in a little too deep. Some chapters seemed to resemble academic seminars – though they were thoughtful and on-topic, they had me longing to get back into the sensory world.

Amidst his big thick manuscript I spied a gorgeous small book.

Carefully I sketched to him what I imagined. Cut this. Cut that. Depend on the quick brief chapters, the impressionistic short takes. This writing was so captivating . . . why not make a whole book of it?

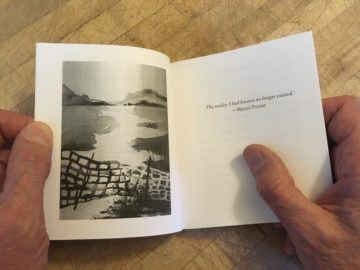

Reader, he saw the vision. He took it up as his own and began the rewrites. For the chapters that we kept – about half of the original manuscript – I offered suggestions (again: carefully!). And the result was everything I had hoped for and more. His ego was never in the way. In every case he sought the spirit of my marks and cross-outs and comments. When I asked him to shorten the too-long, too-smart sentences, he turned them into short sharp sentences that smarted. Here is a sample, the entire section called “Petroglyph Lake”:

“You can see all the way to nowhere in all directions from the road in. Petroglyph Lake appears right at the moment you give up on finding it. A quiet lake that announces nothing. The glyphs wait for you if you can find them, they’ve been waiting for some time.”

In my three decades of teaching writing – in college freshman comp, research paper, and creative writing classes . . . in workshops and seminars with adult writers, many of whom were already accomplished and published . . . and in graduate writing programs: Parker was absolutely the best re-writer I ever encountered. It was breathtaking.

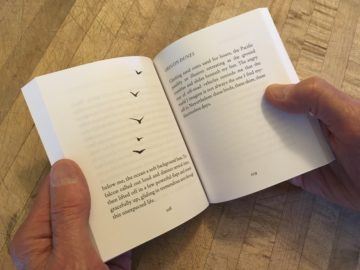

And so is his little book. I wanted real beauty in the hand and for the eye, to go with the gorgeous language. I commissioned Portland artist Alex Hirsch to read the text and experiment with in-the-moment sketches. Her hand, with brush, pen, and ink so light and so responsive, gave us our perfect little book.

And so is his little book. I wanted real beauty in the hand and for the eye, to go with the gorgeous language. I commissioned Portland artist Alex Hirsch to read the text and experiment with in-the-moment sketches. Her hand, with brush, pen, and ink so light and so responsive, gave us our perfect little book.

And that book was honored beyond what I could have dared hope for: named by Kirkus Reviews as “One of the top 100 indie press books of 2018.” Kelson Books is a tiny enterprise. This was an amazing result.

And that book was honored beyond what I could have dared hope for: named by Kirkus Reviews as “One of the top 100 indie press books of 2018.” Kelson Books is a tiny enterprise. This was an amazing result.

The collaboration of editor and writer; the discovery of beauty and insight from unrenowned authors; the good books appearing from small presses all over the country – yes, all over the world: this is the answer to the monotonous ocean of fame created by Big Publishing. Like little waves breaking on strangely original shores, we go on doing good work in our corners and coigns, our private inlets and islands and harbors of humanity.

And lest I make myself look too good in this telling, let me acknowledge that this same editorial creativity and patient nurturing had been extended to me, too. Way back in 1988, Jo Alexander of Oregon State University Press had the vision to say yes to the manuscript of my first book – though it was, at that stage, poorly shaped and repetitive. She saw beneath the surface flaws. She told me those empowering Perkins words: We’ll take a look at this again, if you rework it. And then she told me how.

She must have done this countless times in her thirty years at OSUP, whose first allegiance, like that of other small-press publishers, is to talent.

* * *

It is a kind of gloomy fun to lament the commercialization of art and the short-fingered vulgarians who have taken over publishing (or movies, or the galleries, or . . .).

Yet who has ever solved the messy indignity of a soaring mind contained in a body of necessitous mud? Surely this is the core struggle of sentience. The demands of the flesh mock the life of the mind. And vice versa. It takes a sort of Claude-Rains delivery to be “shocked – SHOCKED!” that elevated pursuits are interwoven with crass practicality. Sullied. Enlivened. What you will.

So . . . I decline to be horrified. I do not lift the hem of my garment. I merely say: somehow, anyhow, the poets (of all genres) must get into print. The Mozarts must be heard, the Bachs must compose their fugues of astonishing complexity, no matter what the aldermen and bankers say about it.

And one way the poetry gets printed, just now, is through the efforts of small presses and their editors. So rejoice!

***

Coming in 3QD: I look forward to examining small-press publishers in several more essays, one on nonfiction and one on poetry. I’ll zero in to review a few exceptional books. This will be such fun! The riches are astonishing.

See you next month.