by Andrea Scrima

“If the spirit of the fox enters a person, then that person’s tribe is accursed.”

1.

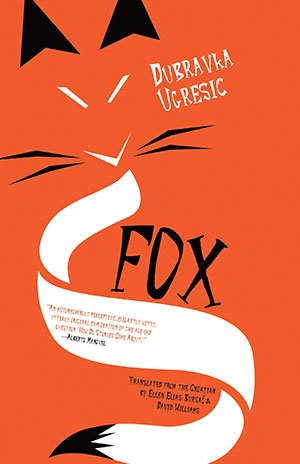

In his 1953 essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” which postulates two quintessential moral dispositions at the heart of history’s main opposing ideologies, Isaiah Berlin divides the world’s influential writers into two categories of thought. Elaborating on Berlin’s dichotomy in her latest book Fox, which came out the spring of 2018 in English translation, Dubravka Ugrešić distinguishes between “those who write, engage, and think with recourse to a single idea (hedgehogs), and those who merge manifold heterogeneous experiences and ideas (foxes).” Clearly, the fox sounds more enticing; Berlin equates the hedgehog with authoritarianism and totalitarianism, while the fox is deemed liberal and tolerant. The only problem is the questionable reputation it’s earned among the world’s oldest mythologies, fairytales, and legends: whatever it might have going for it in the way of “pluralistic moral values,” the fox has long been accused of “cunning, betrayal, wile, sycophancy, deceit, mendacity, hypocrisy, duplicity, selfishness, sneakiness, arrogance, avarice, corruption, carnality, vindictiveness, and reclusiveness.” That’s quite an indictment—and all the more reason for Ugrešić to select the wily animal as patron saint of her new book.

Fox is subtle, virtuosic, and jarring; it’s also mordantly funny. In light-footed, deceptively playful detours and digressions, the book skips from Stalinist Russia to an American road trip with the Nabokovs, academic conferences and literary festivals to the largely untold story of the Far-East diaspora of persecuted Russian intellectuals on the eve of World War II. Fox is a novel, but its formal structure poses a challenge; some chapters read as essays, some as autonomous short stories, and while many recurrent threads reveal themselves upon closer inspection and reflection, it requires attention to unravel the author’s narrative strategy. Read more »

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing  Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.

Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.

All of human life is quite literally coded into two long, complementary strands of genetic material that fold themselves into a double helix. When cells divide, copies of this genetic code must be made – a process that is known as replication. The double helix unwinds, and a “replication fork” makes its way down the helix in much the same way that a slider separates the teeth of a zipper. Once separated, enzymes get to work on replicating them. Except, only one of the strands is replicated continuously. The second strand is replicated piecewise first, and these pieces – called Okazaki fragments – are then fused together.

All of human life is quite literally coded into two long, complementary strands of genetic material that fold themselves into a double helix. When cells divide, copies of this genetic code must be made – a process that is known as replication. The double helix unwinds, and a “replication fork” makes its way down the helix in much the same way that a slider separates the teeth of a zipper. Once separated, enzymes get to work on replicating them. Except, only one of the strands is replicated continuously. The second strand is replicated piecewise first, and these pieces – called Okazaki fragments – are then fused together. Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.

Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.