by Philip Graham

I am a writer, not a musician. I play no instrument, and I confine my singing to the car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

Public acclaim is simply the last step in a long fraught journey. Many years ago a friend, whose first novel had begun climbing the bestseller lists, privately complained to me that book reviewers and journalists had dubbed her an “overnight success.” As she rightly pointed out, there is nothing “overnight” about writing a novel.

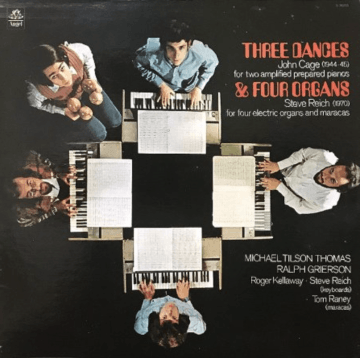

My unlikely musical debut was the end result of a long and circuitous path, a path that closely tracked with my love of minimalist music. While there are many possible ways to tell this story, a good place to start would be my days as an eager undergraduate, and my attendance at an early performance of Steve Reich’s Four Organs at New York’s Shakespeare Public Theater in the fall of 1971.

I had some idea of what to expect. I already admired the minimalist composer Terry Riley’s In C and Rainbow in Curved Air, as well as some of the rock music influenced by him, like Soft Machine’s Third album, and The Who songs, “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

I had never been to the Public Theater’s concert hall, so I wasn’t sure if the elevated stage that faced a semi-circle of tiered seats was a regular feature of the performing space. Six feet high and accessible only by a ladder, that stage looked a little makeshift to me. Four musicians perched at the top and sat before four Farfisa organs (an instrument beloved of garage rock bands like Question Mark & the Mysterians). A fifth musician held a pair of maracas, and began the performance by shaking them in a steady beat. The organists followed, playing at first a four-note theme in unison that slowly fell out of lockstep, especially that last note, which was increasingly held and stretched nearly to the breaking point. The music roared as loudly as any rock concert I’d attended.

After a few minutes, boos rang out, then vocal demands for the music to stop. More than once ironic clapping rippled through the audience, a pointed hint that enough was enough, can’t this be over?

I closed my eyes to escape some of the drama and concentrate on the music’s repetition, which masked a relentless, incremental change. The transformations reminded me of the Byrds, my favorite rock group at the time. When Roger McGuinn played his electric twelve-string Rickenbacker guitar, those six pairs of closely-lined up strings vibrated into overtones, resonated into complex patterns.

repetition, which masked a relentless, incremental change. The transformations reminded me of the Byrds, my favorite rock group at the time. When Roger McGuinn played his electric twelve-string Rickenbacker guitar, those six pairs of closely-lined up strings vibrated into overtones, resonated into complex patterns.

Yet the protests prevented me from fully concentrating. An older woman approached the stage, climbed its ladder, and shouted at the musicians, “Stop, please stop, I’m begging you. Stop!” Maybe this was why Reich and his fellow musicians performed on a stage so high above the audience—it served as a high-altitude moat against a provoked public. The woman soon gave up and then, oddly, returned to her seat. If she hated the music, why not leave?

Several ear-splitting minutes passed, and then the four organs stopped, in unison. The shock of silence lasted for a few seconds, until someone shouted, “Thank God!” This served as a permission slip for all the other disgruntled members of the audience, and their boos rang out louder than before.

I loved the music. Along with the other half of the audience that had embraced the experience of being overwhelmed and challenged, I shouted my “Bravo!” against the protests. What an exhilaration of competing voices! Was this what both raucous sides felt in Paris in 1913 at the end of Stravinsky’s premiere of Rite of Spring?

I enjoyed the excitement so much that, a little over a year later, when I saw a Carnegie Hall notice that Michael Tilson Thomas would be conducting not only my favorite work by Bartok, Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, he’d also be performing as one of the keyboardists for Reich’s Four Organs, I knew I had to attend. What might happen this time, in such a storied concert hall?

favorite work by Bartok, Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, he’d also be performing as one of the keyboardists for Reich’s Four Organs, I knew I had to attend. What might happen this time, in such a storied concert hall?

From a nose-bleed seat in the balcony (the only ticket I could afford), I watched what turned out to be another overheated fray below. A few people left their seats and filed out, soon enough morphing into an orderly stampede. Others stayed and shouted. When a woman walked to the edge of the proscenium stage and waved her arms, shouting who-knows-what, I sat too far away to hear her over the other protests. Could this have been the same angry woman from the Public Theater concert, did she suffer from some serial addiction to audience theatrics? If so, wasn’t I her mirror image, attending not to protest but to cheer?

*

The next step along the path to my briefest of musical careers arrived in the fall of 1973, shortly after I graduated from college. I’d driven to St. Mark’s Church to see if I might get myself on a list of readers for their open mic night, but the office was closed. Later, at a nearby cafe, when it was time to settle my lunch tab I realized how close I was to broke. Carefully counting my limited bills and change, I noticed that Steve Reich and another up-and-coming minimalist composer, Philip Glass, sat at a nearby table.

The poor abused composer Steve Reich! How could I not tell him I’d once been among those shouting “bravo”?

As I approached, Glass rose and kindly asked, “How much do you need?” He must have noticed my coin counting and thought I’d sidled over to panhandle.

“No, I’m good,” I said. “I just wanted to tell Mr. Reich how much I enjoyed Four Organs at the Public Theater and Carnegie Hall.”

Perhaps curious why I’d attended not one but two performances, Reich asked, “Are you a musician?”

“No, I’m a writer. I just love your music,” I replied, and his serious demeanor cracked open into un-selfconscious pleasure.

Little did I know that, fifteen years later, if only for the shortest of times, I would indeed be able to call myself a musician.

*

Because of Glass’s kindness and Reich’s unreserved pleasure at meeting a fan, I felt a distant proprietary pleasure when the minimalist revolution took hold in contemporary music in the late 1970s. I then lived in Charlottesville, Virginia while my wife, Alma Gottlieb, pursued her graduate studies in cultural anthropology. I was the proud possessor of the boxed set of Philip Glass’s transformational minimalist opera, Einstein on the Beach, and Steve Reich’s equally groundbreaking Music for 18 Musicians. But I had to be careful about playing the music in our small apartment, because Alma had limited patience for the music’s repetitions. Mostly I waited until she left for class or the library before placing needle on vinyl.

Alma’s first fieldwork research, among the Beng people of Ivory Coast in West Africa, led her to hear rhythm differently. During our fifteen months of living in two small villages, we frequented dances and funerals where a battery of drums filled the air for hours or even days, the interlocking rhythms settling into us like the sound of pervasive rain.

So when we returned to the U.S. at the end of 1980, Alma easily converted to the pleasures of Einstein on the Beach. She even requested from time to time that I break out the boxed set. The music’s propulsive rhythms gave us a form of deflected nostalgia, bringing us back to our life among the Beng. This shouldn’t have been a surprise. Steve Reich had studied the drumming of the Ewe people in Ghana, and though Philip Glass’s influences came mainly from India, he too had broken with the rhythmic strictures of Western music. Alma and I became such fans that we once drove 200 miles from Juniata, Pennsylvania (home of my first college teaching gig) to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, to attend the 1981 premiere of Glass’s Satyagraha, an opera about Gandhi that entranced us all the way to the work’s final yearning “Evening Song.”

*

Minimalism might have become the ascendant form of contemporary classical music, but in 1983 when I began a one-month writing residency at MacDowell, I encountered a batch of composers who were embittered that their twelve-tone works were no longer considered revolutionary. The mere mention of Glass or Reich inspired rants about “wallpaper music.” They reserved their greatest contempt, however, for the air-wave ubiquity of rock and roll, whose complexity they said barely rivaled “Three Blind Mice.” One young composer declared, over the residency’s communal breakfast table, “It would be like you writers being forced to read Dick and Jane every day.”

Twelve-tone music wasn’t an impossible stretch for me—I loved Alban Berg’s soulful, mournful Violin Concerto, and Stravinsky’s lively, tricky ballet score, Agon. But the academic composers laboring away at MacDowell squeezed out too much emotional juice with their mathematical games. To my untrained ears, their music sounded like a cat padding unsteadily across a piano keyboard.

A MacDowell residency tradition encouraged the various Fellows—whether poets, writers, artists or composers—to give evening presentations of their work. We dreaded the nights when a composer’s turn came to strut his or her stuff, because they almost always broke the rule of keeping a presentation short. Once, a needy middle-aged composer played tapes of his two atonal symphonies, each lasting nearly an hour. We writers and artists suffered through it politely, silently. After all, we had to share both breakfast and dinner with each other every day. We all took a risk with those evening presentations—the approval of our peers meant a lot.

When the second tape blessedly ended, another MacDowell tradition needed to be observed: approaching the evening’s presenter with whatever praise could be enthusiastically bestowed or cleverly mustered. But after those two interminable symphonies, what could we possibly, honestly, say?

A poet and old hand at residencies for decades sat among us, and he said, “Just follow me, I know what to do.” He walked up to the Offending Composer, patted him on the back and said in a friendly hearty voice, “Well, you’ve done it again!” We nodded our heads in agreement, and the Offending Composer beamed.

One night, a small group of writers and artists decided to stay up late and commandeer MacDowell’s only television, in order to watch the Talking Heads debut a song on the David Letterman show. As “Burning Down the House” picked up speed, one of the Offending Composers, the Fellow particularly enamored of wallpaper and Dick and Jane comparisons, wandered by and remarked, “Only two chords? I could do that.”

No one took the bait. Seeing that he couldn’t spoil our pleasure, he sighed and continued his wandering.

Though overt silence had been our defense, in my mind there was much to say. “If it’s so easy, why don’t you give it a try?” was the reply I kept locked in my head, along with a memory I’d refrained from sharing. Of the many tapes I’d brought along for over a year of living in an African village, only two songs interested our village neighbors. One was by the Talking Heads: “I Zimbra,” from their album, Fear of Music. Co-written by David Byrne and Brian Eno (himself a minimalist pioneer), the song’s insistent staccato rhythms, the vocals sung in a made-up language, and the chirpy guitars seemed to cross a cultural divide and almost always drew the children of the village to our compound—a not-so-easy achievement that I admire to this day.

*

By the late 1980s, minimalism’s triumph had become so mainstream and watered down that it even served as background music in car commercials. I lost my ear for the minimalist experience, lost my desire to attend once again to small, overlapping changes.

The brand wasn’t helped by Philip Glass’s prodigious output of yet another opera, symphony, concerto or what-have-you, all of it seemingly cut from a similar pattern. I’ve always been suspicious of the prolific. I’m all in for a strong work ethic, but an overabundance of product suggests that there might not be enough interior friction within an artist, not enough hard questions that struggle to be answered.

In 1988, while serving my third year as an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Illinois, I came to a point where I needed to escape the toxic world of academic bickering, needed an emergency head-cleaning weekend trip to New York City. With Alma’s kind blessing (even though I’d be leaving her alone with a toddler for a few days), I booked a flight.

How closely I hovered on the verge of my brief musical career.

In the city, I conducted some literary business with my agent and met with a few writer friends. On my last evening, while walking past Lincoln Center, a poster  caught my eye. It announced a concert of classic minimalist compositions at Alice Tully Hall that would start in less than an hour. A wave of nostalgia swept over me, and on a whim I bought a ticket and soon settled into the half-filled auditorium.

caught my eye. It announced a concert of classic minimalist compositions at Alice Tully Hall that would start in less than an hour. A wave of nostalgia swept over me, and on a whim I bought a ticket and soon settled into the half-filled auditorium.

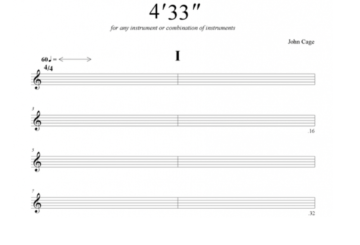

Though the program included some favorites, Terry Riley’s gorgeous G Song for string quartet, and Arvo Part’s languid Spiegel in Speigel, as the evening progressed I had to admit that the music had indeed lost the tang of the new. John Cage’s 4’ 33” was scheduled near the end of the program, and I got the joke: though 4’33” pre-dates all of minimalism by decades, it might as well serve as the genre’s logical last anorexic step. I had attended a performance of Cage’s 4’33” once before, when a violinist stood silently beside her instrument for the first movement, a flautist kept quiet for the second, and a timpanist didn’t move a muscle during the third, all adding up to four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. I understood the point. Yes, the world is filled with accidental and incidental sounds, and the absolute silence of Cage’s “music” was meant to encourage us to hear those otherwise ignored soundscapes.

Yes, the world is filled with accidental and incidental sounds, and the absolute silence of Cage’s “music” was meant to encourage us to hear those otherwise ignored soundscapes.

In the Alice Tully Hall performance, a single clarinetist held the stage, doing triple duty on the hard work of silence. Outside, a bus passed by, a siren went off. Someone in the audience suppressed a cough. Cage’s point no longer impressed me. I already knew that New York City had traffic, that police sirens were not uncommon, and that every audience harbored a discrete cougher. No surprises there. I didn’t want to release myself to another four-and-a-half minute silent lecture that all sounds, however unlikely, deserve love. Somewhere in the second movement (Where? Who’d know without a stopwatch?), an uneven battle began within me.

On one interior shoulder, the Angel of Classical Music Compliance urged that I observe the long-ingrained behavioral pattern of sitting and listening quietly, never applauding between a composition’s movements, and feeling guilty for any throat cleared or seat rustled. On my other shoulder, to my horror, sat the Devil of Woman Who’d Screamed at Steve Reich, hissing, “Why not lodge a complaint?” Then she was joined by the Devil of Offending Composer from MacDowell, who whispered, “Even you could do that” (which was certainly true, I could easily stand beside a silent instrument, whatever it might be).

Register a protest? Never.

Venture a cough? That would only be subsumed into Cage’s larger point. But if someone could cough, why couldn’t someone else sing?

What if I broke into song?

A ridiculous thought. I hadn’t sung in public since my abrupt departure from the sixth-grade chorus.

I’d never contributed much to the chorus to begin with. First, I didn’t care for the teacher. She was mean, quick to belittle anyone’s slightest mistake. Second, I’d noted that the boys with a high tenor voice like myself were placed in the girls’ section. I didn’t need another mark against my already precarious middle school social standing, so I lowered my voice into the boys’ section and became a spy in the house of baritones. However, I found it too uncomfortable to sing lower than my normal register. I often simply mouthed the words of whatever song we practiced, my silence covered by the voices around me.

One day in chorus class, we sat in the auditorium’s plush chairs while the teacher stood on stage and lectured about something no doubt important for our forthcoming performance. But at the moment, I was more interested in sharing my enthusiasm for an Edgar Allan Poe story, “The Pit and the Pendulum,” with my friend Gordon.

friend Gordon.

I’d read it the night before, and its gruesome premise still haunted me. “It’s about this guy getting tortured,” I half-whispered to Gordon, “and there’s this ax swinging back and forth, back and forth above him, and every time it swings it drops a little lower, like this.” I helpfully demonstrated with my hand. Gordon, however, stared straight ahead, eyes wide, and when I turned to follow his gaze, there stood the chorus teacher, watching us.

“Are you done?” she asked.

“Yes,” I managed to squeak. Without waiting for a further reply she announced my banishment from the chorus and sent me packing back to my homeroom.

My punishment turned out to be a blessing—in effect, it gave me an extra study hall where I could read to my heart’s content. When word arrived that the chorus teacher was willing to reconsider my exile, I declined to return. Her banishment taught me that, while I loved music, I loved literature much more. It had been a decisive step, I eventually realized, on my path to becoming a writer. And the beginning of my 25-year drought of public singing.

Yet there I sat in Alice Tully Hall, seriously contemplating breaking that drought.

While I couldn’t imagine falling so low as to spiritually align myself with the likes of those who’d shouted at Steve Reich and his ensemble long ago, a little ear-worm rose up out of a quite unlikely nowhere within me: the chorus to a lesser James Taylor hit song, his cover of “Handy Man.”

How could I even consider singing this? If Cage’s 4’33” was designed to encourage one’s attention to the sounds we often ignore, and recognize the pervasive random soundscape we unthinkingly filter out, wouldn’t a brief shout-out to a James Taylor hit song be more acceptable if we heard someone singing it outside on the sidewalk?

I wavered on the precipice of breaking more than one of my life’s silences. And about time, too. Hadn’t I silenced my tenor voice in sixth-grade chorus? Sat silently, dutifully, through two hours of uninspired twelve-tone music? Kept my as-yet-untenured mouth shut during the childish machinations of faculty meetings?

I began to sing, in my little-used tenor voice, and hoped I wouldn’t stray too far from whatever key I was attempting:

Come-a, come-a, come-a, come-a,

come, come-a come-a

Yeah, yeah, yeah

My little outburst lasted no more than six seconds. When silence resumed, a man sitting a few rows ahead turned with a scowl, raised a finger to his lips, and shushed me. A few people laughed at the irony of this second breaking of silence, and then the third movement commenced and completed without further interruption.

And that was that. The next day I flew home to Illinois.

The Monday after my return, I sat in the living room, coffee cup by my side, as I paged through the Arts and Leisure section of The New York Times, and I came upon a review, by Allan Kozinn, of the concert I’d attended. Near the end of his review, he nicely described Cage’s piece as “a silent work in three theoretical movements,” and then continued: “The work, overseen by David Krakauer, a clarinetist, elicited giggles from the audience, and a burst of scat singing from one listener.”

“A burst of scat singing from one listener”? Over and over I read those eight words crafted for my brazen solo.

I realized I might be the only person in the world whose entire musical career, performed at the revered Alice Tully Hall, and stretching across the span of a mere six seconds, was covered by The New York Times. Here was the very definition of meteoric success. How could I possibly top that?

So, I decided my musician days were over.

Besides, I had books to write.

*

My Review of My Reviewer Coda

As someone who has somehow managed to publish over 40 book reviews for various publications over the years, I’ve come to understand the limitations of the genre, having become familiar with the sort of mistakes and inattention to detail that all reviewers from time to time display. I like to think that my anonymous six-seconds of glory was the shortest musical career in recorded history. Therefore, much more attention should have been paid by the reviewer from The New York Times.

Let’s begin with the genre of music I sang.

Scat singing? More like folk-pop crooning. Apparently, Allan Kozinn, though well-versed in the history of the classical music sub-genre of minimalism, was woefully unfamiliar with James Taylor’s greatest hits oeuvre.

Then, of course, there’s the issue of my double anonymity. Not only did Kozinn not search me out after the concert and ask my name, the best he could come up with was a non-gendered “one listener.” How would that help any reader visualize the performer?

And where was there a hint of the quality—if any—of my tenor turns of phrase?

Worse, the reviewer got the chronology of events entirely backwards. My singing came first, followed by a harsh shushing (not even mentioned!), which in turn engendered the ripple of laughter that he described as mere “giggles.”

Perhaps I am too harsh. I mentioned earlier the understandable limitations of reviewing. How could Allan Kozinn, however accomplished a music critic, have possibly known of the 25-year journey behind my six-second vocal outburst, how could he have possibly identified, within that scrap of a song he’d clearly never heard before, any of the various silences that at that very moment were being defeated inside me?