by Sarah Firisen

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

At the beginning of lockdown, my friend and former colleague Catherine and I started talking about the future of work. This conversation turned into a book that we’re currently writing, and a companion podcast called The Impromptu Game Plan. Our overall premise was, “for the last decade, the digitization of jobs, primarily through automation, has been an exponentially disruptive force. And then COVID-19 hit. COVID-19 has devastated entire industries that may never come back, or at least come back in their previous form. It further disrupted the world, the economy, the workforce in ways that we will be living with long beyond the end of the spread of the virus. The economic disruption caused by lockdown has accelerated the workforce displacement already underway due to automation and other technology disruptions. We’re now living through a perfect storm of human-made and natural disruption that will cause as much reordering in society as the industrial revolution did, perhaps more so.” We thought there was an interesting germ of an idea there, but we had no idea how prescient we would turn out to be. Read more »

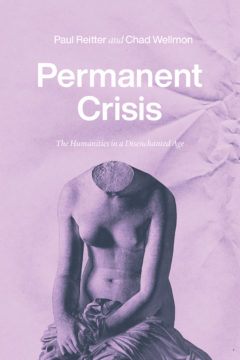

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

‘

‘ In

In

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.

Time isn’t what it used to be. The pandemic has altered our perception of it. This is why time is no longer quite as valuable as it was before we were suddenly assaulted with too much of it. It used to be a commodity in short supply. It’s even been called a currency (time is money), but the reverse was never true. No matter how many billions Mr. Bezos has, he has no more hours in his day than I do.

Time isn’t what it used to be. The pandemic has altered our perception of it. This is why time is no longer quite as valuable as it was before we were suddenly assaulted with too much of it. It used to be a commodity in short supply. It’s even been called a currency (time is money), but the reverse was never true. No matter how many billions Mr. Bezos has, he has no more hours in his day than I do. The evidence that mass media can cause physiological responses in humans is so evident in our everyday experience that it’s easy to ignore. Subliminal muzak makes our fingers tap lightly on our grocery carts. Billboards with sexy models flush our cheeks during our daily commutes. But not all such stimuli are subtle. For those media products whose main purpose is to cause a physiological response, genre labels serve as warnings—e.g., we label items that make us laugh as comedy, items that turn us on as pornography, or items that trigger our fight-or-flight response as horror. Modern people have complex attitudes toward media that invoke a physiological response, and practitioners of such genres alternatively experience intense celebration and intense censure.

The evidence that mass media can cause physiological responses in humans is so evident in our everyday experience that it’s easy to ignore. Subliminal muzak makes our fingers tap lightly on our grocery carts. Billboards with sexy models flush our cheeks during our daily commutes. But not all such stimuli are subtle. For those media products whose main purpose is to cause a physiological response, genre labels serve as warnings—e.g., we label items that make us laugh as comedy, items that turn us on as pornography, or items that trigger our fight-or-flight response as horror. Modern people have complex attitudes toward media that invoke a physiological response, and practitioners of such genres alternatively experience intense celebration and intense censure. Some decades back the typical voting pattern in many democracies used to be that the rich and upper middle classes used to vote in general for right-leaning parties, while the relatively poor voted for left-leaning parties. But in recent decades this pattern has been shifting: many of the professional or more educated voters in some of those countries are increasingly going for left or green parties, while many of the poor working-class voters are turning to right-wing parties, sometimes led by populist demagogues. Thomas Piketty and his associates in a new paper issued by the World Inequality Lab have provided data to show that for 21 western democracies the more educated voters have over the years become more left supporters than the less-educated voters. Piketty has described this elite division between high-education and high-income people colorfully as that between the Brahmin Left and the Merchant (the corresponding Indian caste term would have been ‘bania’) Right. He does not go much into explaining this pattern but it is clear that as education expands (measured by average years of schooling of the adult population) the left or center-left parties now can have a viable base even in the relatively rich or upper middle classes. Education often makes one appreciate more liberal values, which may sometimes outweigh their worries about higher taxes that the left parties may inflict.

Some decades back the typical voting pattern in many democracies used to be that the rich and upper middle classes used to vote in general for right-leaning parties, while the relatively poor voted for left-leaning parties. But in recent decades this pattern has been shifting: many of the professional or more educated voters in some of those countries are increasingly going for left or green parties, while many of the poor working-class voters are turning to right-wing parties, sometimes led by populist demagogues. Thomas Piketty and his associates in a new paper issued by the World Inequality Lab have provided data to show that for 21 western democracies the more educated voters have over the years become more left supporters than the less-educated voters. Piketty has described this elite division between high-education and high-income people colorfully as that between the Brahmin Left and the Merchant (the corresponding Indian caste term would have been ‘bania’) Right. He does not go much into explaining this pattern but it is clear that as education expands (measured by average years of schooling of the adult population) the left or center-left parties now can have a viable base even in the relatively rich or upper middle classes. Education often makes one appreciate more liberal values, which may sometimes outweigh their worries about higher taxes that the left parties may inflict. Among all the fascinating mythical creatures that populate the folklore of various cultures, one that stands out is

Among all the fascinating mythical creatures that populate the folklore of various cultures, one that stands out is