by Nicola Sayers

I recently spent a couple of years living in Chicago, a city that I loved so much it still looms in my daydreams as my ‘one that got away’. During that time, in addition to exploring the many and varied neighbourhoods that make up the city itself, I also found myself regularly drawn further afield, where I developed something of an unusual pastime. I would take the train from the city, where I lived, to one of Chicago’s many suburbs — Winnetka (of Home Alone fame), Oak Park (of architect Frank Lloyd Wright fame), Glen Ellyn (of absolutely no fame) — and spend the day wandering aimlessly, dawdling, observing. Flâneur-ing, if you will.

The flâneur is an unlikely figure in the American suburbs. Implausible, even. The term is best known from the writing of Walter Benjamin, in whose reflections on Baudelaire’s Paris the flâneur is seen as an essentially modern — and urban — figure. The flâneur, as (s)he walks, encounters the city as a place of surprising turns, forgotten histories, discordant presents, and unfulfilled pasts.

In explicit contrast to such a Baudelairean scene, theorist Marc Augé describes what he calls ‘non-places’: motorways, hotels, airports; the stripmalls and largely purpose-built neighbourhoods that make up suburbia. If the Baudelairean city is one in which layers of history sit atop and astride one another, are built into its very fabric, it is exactly this presence of the past which is missing in Augé’s non-places. The aimless wanderer is implausible precisely because these spaces — these non-places — have typically been planned from scratch with very specific purposes in mind (transport, commerce, leisure, etc), and it is true, in this vein, that many people move through the suburbs in the way the planners intended: they drive from their houses to the malls when they want to eat, to the gyms at the stripmalls when they want to work out, and so on. Read more »

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

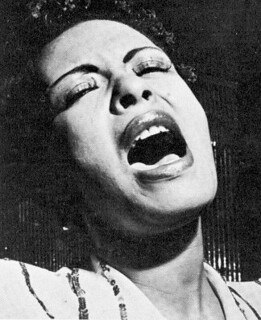

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.