by Thomas Larson

If we include in an overview of JFK’s classical musical legacy, those compositional masterpieces that honored him after his death, two pieces jump out of the field for me: Leonard Bernstein’s Mass and Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings.

Mass was commissioned by his wife, Jackie, to open the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1971. Bernstein used the venue’s function—performance—literally: he stitched together a transmedial work that combined the best of Brahms’ German Requiem, The Who’s Tommy, and his own Candide.

Mass’s subtitle was “a theater piece for singers, players, and dancers.” It featured a rock band within a full orchestra, forty blues, rock, and light opera singers, two choirs, dancers, strolling musicians, and tape sounds produced quadrophonically. Among its highlights for me was Bernstein’s pairing an irreligious element with a Bible-based piety, especially in the gospel/sermon “God Said.” One wasn’t sure how much this jagged little tune embraced the tradition of preaching the Holy Fire or made a parody of it. Most memorable are the choral lines: “And it was good, brother / And it was good, brother / And it was good, brother / And it was goddam good.”

The work is like a top, spinning madly, gyrating and tilting, ready to fall, only to be re-spun by Bernstein’s gift of musical invention—his theatrical blood pumping his multiple moods, which range from meditative to melancholic to bossy to sardonic to unabashedly poppy and sentimental, equally unafraid of the raw and the honest. Read more »

Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together.

Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together. When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

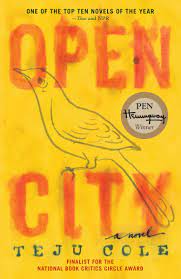

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?