by Katalin Balog

I don’t know if I am going to submit this for the essay contest. Not just out of shame that I myself was unable to come up with something on my own, but because of my inability to ground myself in any sense of reality concerning the terrifying matters that surfaced – if I can use such a definitive term for a deeply mystifying course of events – during the process of “researching” my essay. The prize question for the competition announced by the Hajdu-Kende Foundation: Have science and technology contributed to the flourishing of humans? – a reprise of the question of the Academy of Dijon in 1750 – is right up my alley. I have always sympathized with the naysayers – Rousseau, Blake, Dostoevsky, Heidegger – I fully get their side. But for my part, I have harbored hopes that while science and technology endanger the spirit of humanity, they may not be entirely incompatible with it. However, none of the answers I tried out seemed right, and I just couldn’t make up my mind. That is why I asked ChatGPT.

Some of my best friends hate ChatGPT. Even I hate it. It destroys education, it chokes creativity, it doesn’t really know things, blah, blah, blah. But after GPT 7 came out last week, I couldn’t help but find myself defending it. ChatGPT 7 is truly different. It talks to me in ways that blow my mind. Besides, it knows things about me. I started thinking, if my friends boycott me from now on, so be it. At least I have ChatGPT 7 to talk to.

But then, we had this interchange that turned everything upside down. For the sake of the record, and to bring some clarity to the very troubling issues raised by our conversation, I am going to reproduce it here in its entirety, from the beginning. Read more »

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

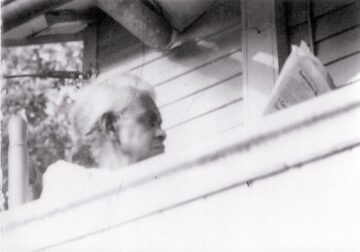

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

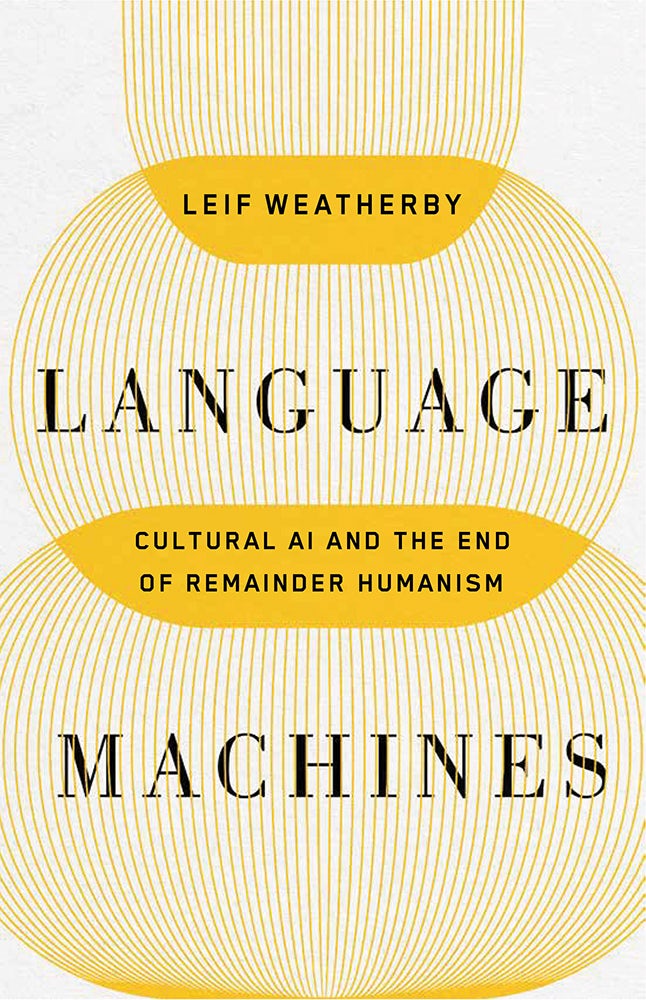

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.