by Thomas Fernandes

In part I we’ve seen how bees fly and generate astonishing metabolic energy just to remain airborne. But what do they do with that flight? As exemplified by nectar foraging, taking advantage of flight also means developing the perceptual and cognitive tools necessary to navigate the world. So far this was a solitary bee’s world but the particularities of honeybee lie in their social organization. Let’s look inside the hive.

Compared to solitary bees, in social bees the hive exists only to propagate the queen’s genes. Workers are sterile and their bodies, shaped by evolution, serve only the collective. Under such selective pressure the initial ovipositor, the egg laying appendage, of worker bees is modified into a barbed, irreversible stinger. In defending the hive, she dies. Only in eusocial species like honeybees does evolution favor such sacrifice for the group. Each worker follows a precise schedule from birth: 12 days of brood care, then wax production for honeycomb construction, then foraging until death, worn out by relentless flying.

This social structure allows for efficient food processing. When a nectar foraging bee returns, the nectar is unloaded to an awaiting younger worker bee and the honey making can start. The nectar is passed mouth to mouth, its sugars broken down by enzymes, then fanned with wings until it thickens into honey. A well calibrated practice that produces a substance which never rots due to its low water content, too tightly bound to sugar to be used by bacteria. This honey storage is how the hive survives winter as a colony, unlike social wasps where only the queen hibernates through winter while the rest of the colony die. It takes 30 kg of honey for a hive to pass winter, each kilo the result of a combined foraging effort amounting to four trips around the globe.

The other food source of bees, pollen, is used to make “bee bread” that will also be stored in combs. Mostly pollen serves to feed the larvae and young bee but cannot be digested raw. Instead, bees will make bee bread by fermenting pollen with honey and saliva creating a digestible protein-rich food that stores through winter.

Yet with 60 000 members and nectar returns that can vary by two orders of magnitude from one day to the next a rigid organization cannot function. Coordination requires adaptability and communication. Bees will communicate information through dances. One such dance is the tremble dance used to coordinate work inside the hive. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

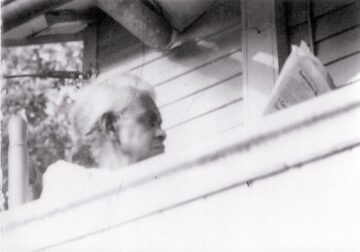

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.