by Rafaël Newman

Fatherhood and motherhood are always a compromise between a form of Nazi eugenics and a compulsion for repetition. —Paul B. Preciado

If it were up to certain contemporary authors, the title of arch-villain—or rather, Worst Person Ever—might go collectively to a particular category of human normally held up as a model of nurturance and care: viz, to anyone who has willingly and consciously engaged in the act of procreation, whether by “traditional” means, or with scientific assistance. Sally Rooney and Ottessa Moshfegh have written very different, equally angry indictments of parents, while those who appear in the works of Jenny Erpenbeck and Deborah Feldman give the Grimm Brothers a run for their money. And Paul B. Preciado, the gender theorist of my epigraph, is joined in his radically downbeat appraisal of human reproduction by Junot Diaz, who has accused dating apps like Tinder of propagating a species of selective racist breeding.

The convention of decrying rather than celebrating parenthood, of course, did not first arise with the Millennials, or even Generation X. In 1818, Mary Shelley chose as the epigraph to Frankenstein Adam’s surly question to God in Paradise Lost (1667):

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?

—a complaint that places culpability for the travails of life squarely on the shoulders of progenitors, who carelessly indulge their arbitrary, self-centered whims (or allow free rein to their rampant libidos) at the expense of hapless future generations. Read more »

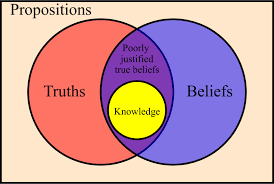

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

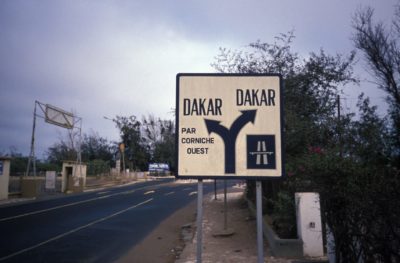

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet.

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet. There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside. Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading  The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.

The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.

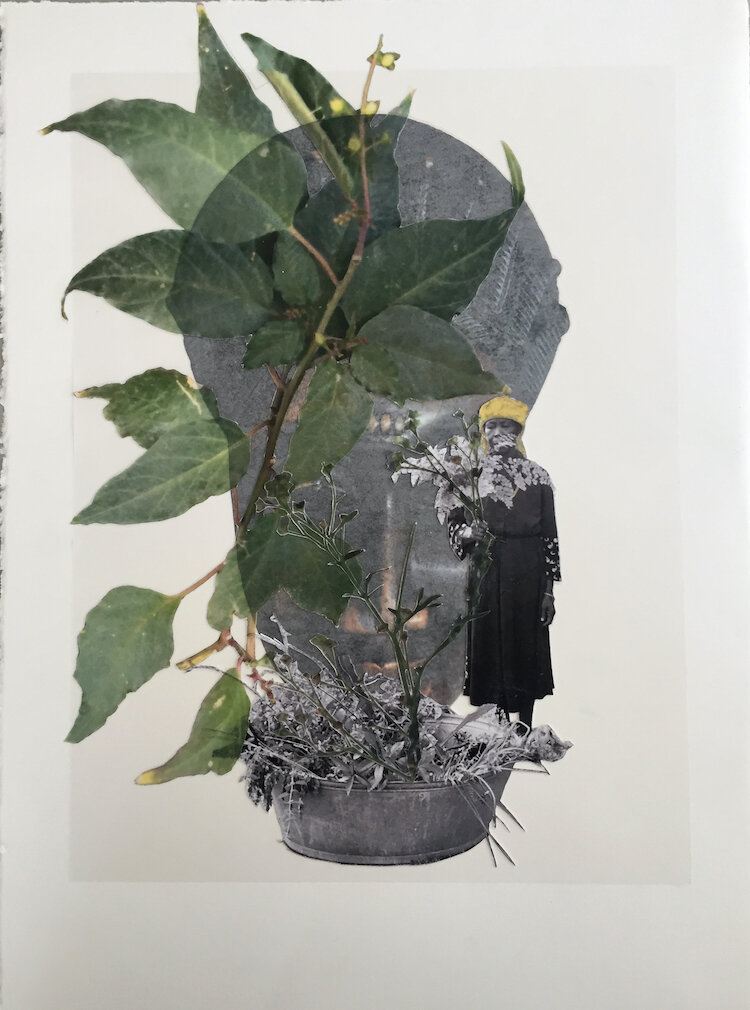

Andrea Chung. From the series Vex, 2020.

Andrea Chung. From the series Vex, 2020.

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.