by Thomas Larson

At breakfast my father asked me what I thought we should do if, in Grandma and Grandpa’s safety deposit box, we found the document identifying his real parents. The year was 1967, and he and I were in Evanston, Illinois, arranging a funeral for his adoptive mother, Elizabeth, who had died suddenly of a stroke. That he was given up at birth he had not learned until his 35th year, when Elizabeth sprang the news on him one Easter. Around the dinner table they were remembering her father, Sam Hill, descendant of a Revolutionary War general, who had often wondered aloud why Elizabeth’s child looked nothing like his parents. Dad had wondered, too.

“Wouldn’t it be funny,” Dad said to his mother that day, “to discover that I —”

“John, as a matter of fact, you were adopted,” she blurted out, vexing his remaining years with an insoluble conflict, namely, whether he should track down his real parents or let them be. Now that we were burying his mother and packing his 86-year-old dad into a retirement home, this bank-vault visit would be his last chance at a birthright.

He’d been up a while, ferrying trash down the back stairs to the cans. Dressed in a freshly laundered shirt, he’d rolled up the sleeves three turns. His gold watch squeezed his wrist, and the dark hair of his arms like a field of evenly charred grass reminded me that his real mother, the Czech servant girl, had given his skin a tannish color. (With the father’s Swedish ethnicity, that’s all we ever knew about his real parents.) My Scandinavian white certainly belied his half-Bohemian origins. Read more »

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

Even though I arrived at Economics with the aim of interpreting history, it soon gave me a more general perspective. First, it showed me the value of precision and empirical testing in thinking about socially important issues. This immediately appealed to me, as two of the first courses I liked in college were on Deductive and Inductive Logic. More importantly, Economics gave me a deeper understanding of the incentive mechanisms that sustain social institutions. It made me think why some of the glib solutions suggested by my leftist friends were difficult to sustain in the real world, unless based on motivations/norms and constraints of people in that world. Why are cooperatives and nationalized industries, suggested as substitutes for private enterprise, often (not always) dysfunctional? Economics asks the question: if there is a social problem, why does it not get resolved by the people on their own, and if your answer is that it is the ‘system’ that is to blame—which was the main message of many leftist stories I read and plays/movies I watched—Economics teaches us to go beyond and look into the underlying mechanism through which that ‘system’ is perpetuated or occasionally broken.

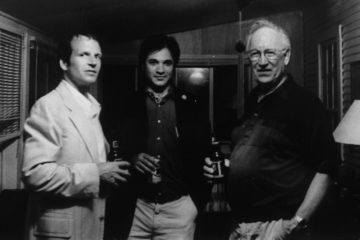

Even though I arrived at Economics with the aim of interpreting history, it soon gave me a more general perspective. First, it showed me the value of precision and empirical testing in thinking about socially important issues. This immediately appealed to me, as two of the first courses I liked in college were on Deductive and Inductive Logic. More importantly, Economics gave me a deeper understanding of the incentive mechanisms that sustain social institutions. It made me think why some of the glib solutions suggested by my leftist friends were difficult to sustain in the real world, unless based on motivations/norms and constraints of people in that world. Why are cooperatives and nationalized industries, suggested as substitutes for private enterprise, often (not always) dysfunctional? Economics asks the question: if there is a social problem, why does it not get resolved by the people on their own, and if your answer is that it is the ‘system’ that is to blame—which was the main message of many leftist stories I read and plays/movies I watched—Economics teaches us to go beyond and look into the underlying mechanism through which that ‘system’ is perpetuated or occasionally broken. Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be.

Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be. Philosophers are prone to define

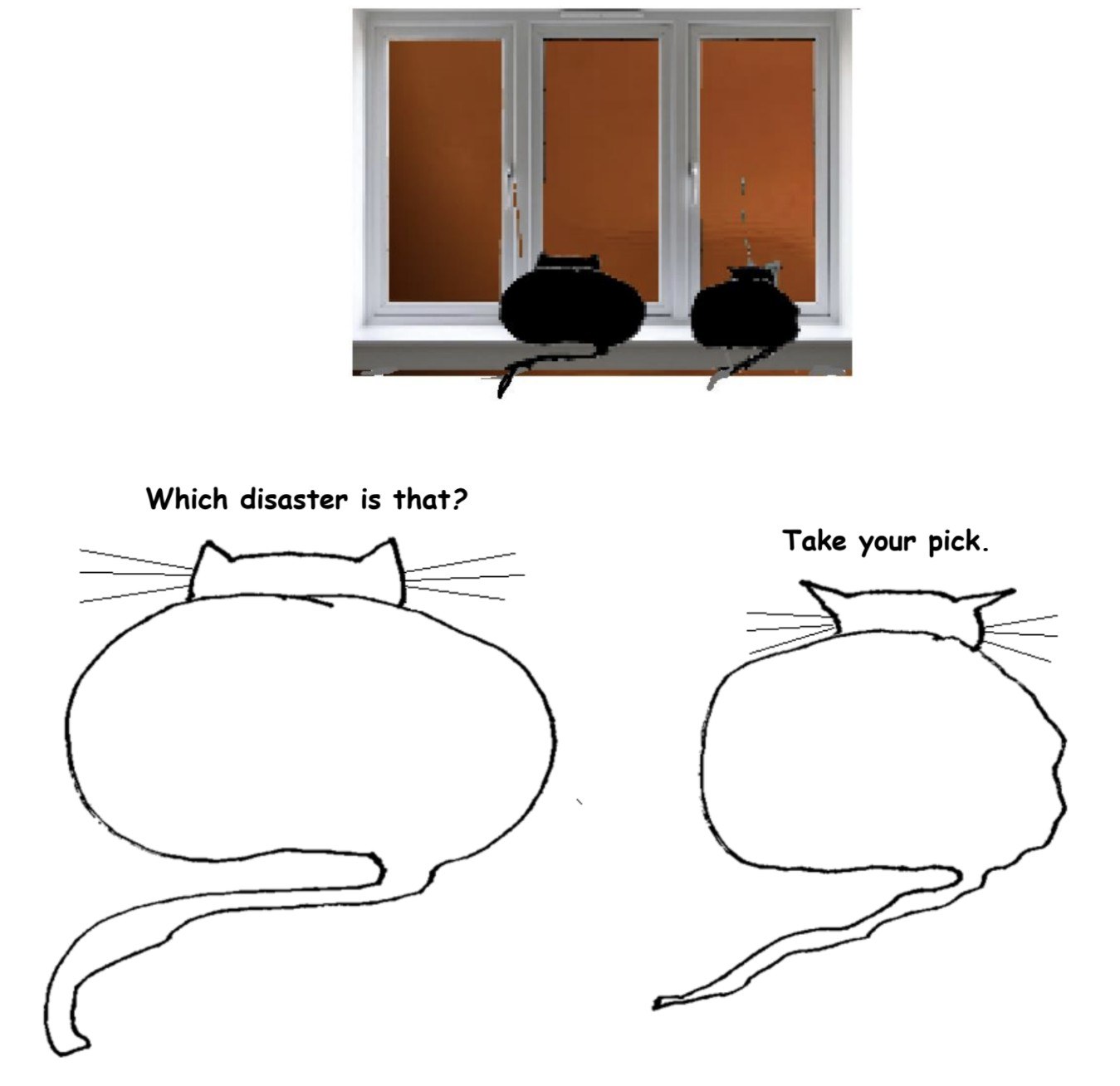

Philosophers are prone to define  This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.