by Eric J. Weiner

The chill in the early morning air hinted of autumn, yet the intensity of the rising sun promised summer heat. Black Tupelo and Red Maple leaves teased memories of fall with premature wisps of yellow and orange. The sky was a depthless cobalt blue, its crystallinity making everything and everyone shimmer. It makes sense that the stunning weather on that particular morning should become a shared referent for our collective dissonance, a common denominator of terror, mourning, and remembrance spanning two decades.

The chill in the early morning air hinted of autumn, yet the intensity of the rising sun promised summer heat. Black Tupelo and Red Maple leaves teased memories of fall with premature wisps of yellow and orange. The sky was a depthless cobalt blue, its crystallinity making everything and everyone shimmer. It makes sense that the stunning weather on that particular morning should become a shared referent for our collective dissonance, a common denominator of terror, mourning, and remembrance spanning two decades.

In the cool air and bright glare of the sun, our glass and steel towers gave evidence of our dominion over nature and, by extension, everything and everyone else. Our arrogance, brilliance, barbarism, and beauty, wrapped in the spectacular innovations and intoxicating aesthetic brutalism of modernity, stretched magnificently into the endless expanse of sky. In a reversal of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, the twin towers, like two fingers of iron and glass rising out of the mud, reached toward the heavens searching for the invisible hand of God. We were the kings and queens of the second millennium, 21st century global conquistadors of culture and finance, the immaculate children of Artemis, oblivious yet intuitively aware of our power as only the powerful can be. A comforting stillness cocooned us in the din of our urban hustle, told us that we were safe, to go about our business, to even pause for a few seconds to admire the tragedy and majesty of it all. Who could deny that we not only had the world by the balls, but Mother Nature on her knees?

It was my first semester as an assistant professor at Montclair State University in New Jersey and the first week of classes. From the highest point on campus, you could see New York City’s iconic skyline. Even though it’s a suburban New Jersey public university in the heart of Essex county, its proximity to New York City allowed me to imagine its ethos as more urbane than it actually was. By proximal association, I would claim New York City my spiritual home, even though I slept in Hoboken and worked in Montclair. Read more »

Margot Livesey’s The Boy in the Field is a mystery novel in the broadest sense of that literary term. Yes, the novel begins with the discovery of a crime, and the perpetrator remains at large for most of the narrative. Yet the “what happened next” of a standard mystery novel concentrates on the three siblings who came upon the victim lying in a field, the reverberations of that event on their young lives, and of the family they are a part of. “Mystery” can reside within all of us, to locate or evade, and that is the deeper reveal that Livesey hunts for in this wise and haunting book.

Margot Livesey’s The Boy in the Field is a mystery novel in the broadest sense of that literary term. Yes, the novel begins with the discovery of a crime, and the perpetrator remains at large for most of the narrative. Yet the “what happened next” of a standard mystery novel concentrates on the three siblings who came upon the victim lying in a field, the reverberations of that event on their young lives, and of the family they are a part of. “Mystery” can reside within all of us, to locate or evade, and that is the deeper reveal that Livesey hunts for in this wise and haunting book.

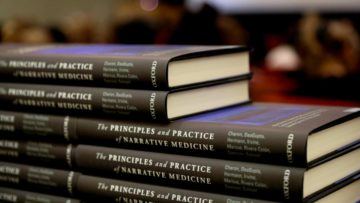

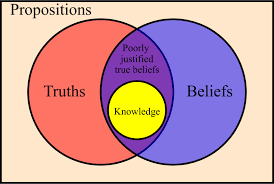

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

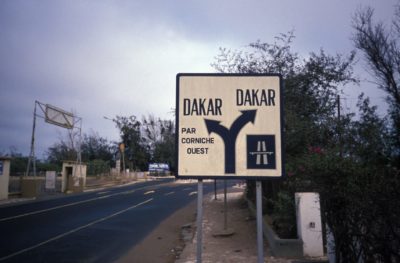

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet.

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet. There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside. Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading  The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.

The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.