by Derek Neal

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

Luckily, a group of Italians came to my rescue. Their English skills were more or less equivalent to my French, and their French, while being much better than mine, was at least comprehensible to my ears. I quickly fell in with them, we used French as our lingua franca, and my language ability rapidly improved.

After a few weeks, I stopped translating what I would say from English to French, and then I stopped forming sentences in my head altogether; I just said whatever I felt like saying, often to the amusement of my interlocutors (for whatever reason, foul language doesn’t seem so serious in another language). Eventually, I reached a point that seems to me a benchmark for all language learners: using a word without knowing its equivalent in one’s native language. A word pops into your head and you’re not sure exactly what it means, but it feels like the right word in the right moment, so you say it and judge the appropriateness of its use based on the reaction of the person with whom you’re speaking. The conversation continues, indicating you’ve made the correct choice. This is, in fact, how most language works, and it’s why learning a language in an educational environment where theory is emphasized over practice can be so difficult. In France, I quickly realized attending courses wouldn’t actually help me learn how to speak French, so I skipped class and went to the cafés instead; my grades suffered, but my fluency increased. Read more »

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema. Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937).

Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937).

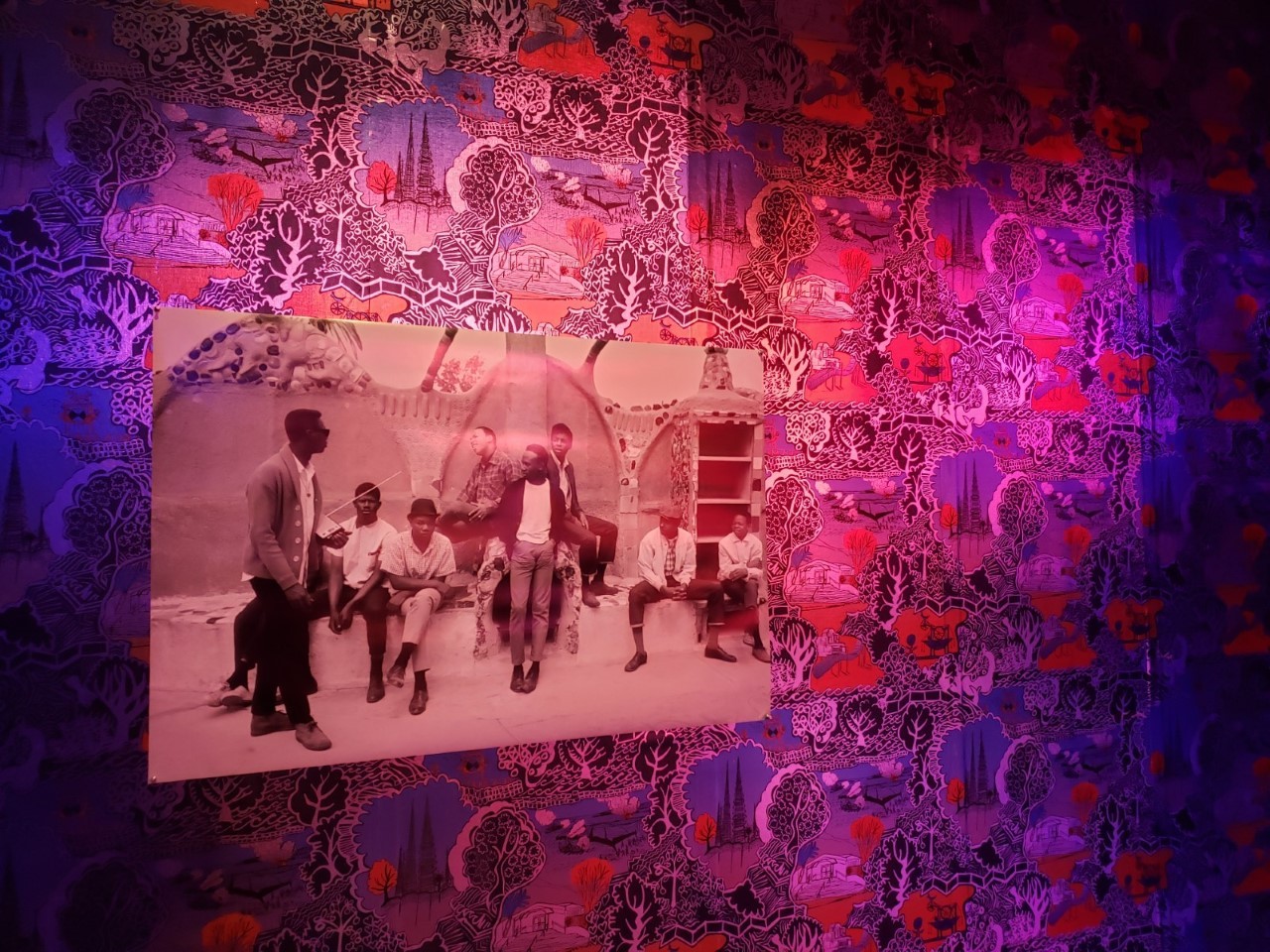

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018.

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018. Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.