by Eric J. Weiner

Ghazal: India’s Season of Dissent by Karthika Naïr[1]

This year, this night, this hour, rise to salute the season of dissent.

Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims—Indians, all—seek their nation of dissent.

We the people of…they chant: the mantra that birthed a republic.

Even my distant eyes echo flares from this beacon of dissent.

Kolkata, Kasargod, Kanpur, Nagpur, Tripura… watch it spread,

tip to tricoloured tip, then soar: the winged horizon of dissent.

Dibrugarh: five hundred students face the CAA and lathiwielding

cops with Tagore’s song—an age-old tradition of dissent.

Kaagaz nahin dikhayenge… Sab Kuch Yaad Rakha Jayega…

Poetry, once more, stands tall, the Grand Central Station of dissent.

Aamir Aziz, Kausar Munir, Varun Grover, Bisaralli…

Your words, in many tongues, score the sky: first citizens of dissent.

We shall see/ Surely, we too shall see. Faiz-saab, we see your greatness

scanned for “anti-Hindu sentiment”, for the treason of dissent.

Delhi, North-East: death flanks the anthem of a once-secular land

where police now maim Muslims with Sing and die, poison of dissent.

A government of the people, by the people, for the people,

has let slip the dogs of carnage for swift excision of dissent.

Name her, Ka, name her. Umme Habeeba, mere-weeks-old, braves frost and

fascism from Shaheen Bagh: our oldest, finest reason for dissent.

As democracies wither and die throughout the world, Karthika Naïr’s ghazal is a passionate and timely celebration of dissent. The places, peoples, and languages of India dance, crack, bleed, demand, and sing their dissent. Soaring through and beyond the borders of India’s post-colonial history, dissent is the oxygen of freedom, scoring the sky with “words, in many tongues.” The “winged horizon of dissent” delineates “what is” from what should be; it is a practice of the radical imagination, an articulation of audacious hope in the long shadows of broken promises and paralyzing fatalism. As the malcontent’s muse, dissent drives the radical desires of dissident artists and intellectuals, the pedagogues of utopic possibilities at a time in which, as Naïr pointedly says,

…there are no small freedoms…I think that India is unfortunately right now living proof for anybody who wants to see the chronicle of an ascension of totalitarianism. This is the chronology: the loss of greater freedoms comes in the slipstream of the denial of perceived “smaller” freedoms. It’s an incremental approach. First, almost always, they come for the books, the art, the movies, the seemingly frivolous things. I would trace it all the way back to the first book banned in independent India, whatever the reason. Because if you can police the imagination, control the freedom of the mind, then everything else will fall in line. There can never be adequate protection for, or vigilance over, these.

Naïr’s poem is also a warning that without dissenting voices, bodies, and minds the promises—explicit and implied—of democracy, like the bones of a malnourished child, will break. Its demise is barely audible against the pitch of rage spewing from the mouths of autocrats and their sycophants throughout the world. These “dogs of carnage” are unleashed, roaming urban streets and dusty squares, rabidly tearing the flesh of hope from the bones of people who have the audacity to dissent.

Laetitia Zecchini writes, “In the powerful, damaged and enraged voices of those who refuse to be muted or unaccounted, we hear echoes [in Naïr’s poetry] of the struggles of Dalits, Adivasis, women, Muslims, but also of all the other (increasingly) threatened minorities whose dissenting views and narratives infuriate the sentinels of cultural and religious majoritarianism: activists, journalists, students, artists, writers…” As a praxis of hope, Naïr’s representation of dissent positions it as an essential element in the struggle against nascent fascism, savage economic inequalities, the manufacturing of ignorance, authoritarian personalities, and the complicity of passive consent that animates so many “free” societies. It is, as Naïr writes, in the last instance, for the children, “our oldest, finest reason for dissent.” In reference to the last couplet of the ghazal, she says, “It was…an exhortation to myself to remember that we are not just fighting for today, we are fighting for tomorrow.”

Naïr’s ghazal is a powerful reminder that dissent will always be a tool of liberation and decolonization for the subaltern; it is a tactic not only of resistance for those of us who exist—for whatever reasons—on the margins of dominant power, but also as a strategy of educated hope. Her words speak to the risks dissent demands from those who have the courage and love to take a position against the status quo of power and domination. It is both a tactic of resistance and a strategy of the radical imagination.

In an age in which domination is celebrated and dissent criminalized, Naïr reminds us that dissent is a way for the subaltern, borrowing language from bell hooks’, to “talk back”; it is a way for the dehumanized, marginalized, and colonized—the oppressed—to amplify their voices, and arm their hearts and intellects against one thing and in the service of another. Stanley Aronowitz in his book How Class Works recognizes the vital utopian thrust of dissent:

It is a time for analysis and speculation as much as organization and protest, a time when people have a chance to theorize the new situations, to identify the coming agents of change without entertaining the illusion that they can predict with any certainty either what will occur or who the actors will be. It is a time to speak out about the future that is not yet probable, although eminently possible. p. 230

Dissent is as much a counter-punch and counter-discourse as it is a thunderous overhand right to the temple of power and privilege; it is a way the silenced make themselves heard over the hegemonic din of entitlement and caste. For those who must hide in the metaphorical doorways of power/knowledge, drown their languages in the bitter saliva of colonial tongues, dissent is a way to be recognized beyond the stereotype and the irrational discriminations of power. Resistance is vital and rebellion has its place, but without conscious, collective, and hazardous dissent[3] there is only the unchecked hegemony of peace.

***********************

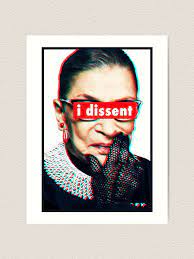

In the United States of America, the Supreme Court is one space in which dissent is conceived and formalized, as Chief Justice Hughes said, as “an appeal . . . to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting judge believes the court to have been betrayed.”[4] Dissent, from this vantage point, acts as a pedagogical signpost; that is, it is a rigorous defense of a minority opinion, one that might be instructive for future generations if and when the real-life implications of the majority decision becomes untenable.[5] Dissent provides the outline and substance of an alternative reading of the law and in some instances a speculative theory about the anticipated impact of the majority’s ruling on the lives of the public. Dissent on the Court is an act of critique, a speculative examination of potential implications, and an alternative conception of constitutional interpretation.

In the United States of America, the Supreme Court is one space in which dissent is conceived and formalized, as Chief Justice Hughes said, as “an appeal . . . to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting judge believes the court to have been betrayed.”[4] Dissent, from this vantage point, acts as a pedagogical signpost; that is, it is a rigorous defense of a minority opinion, one that might be instructive for future generations if and when the real-life implications of the majority decision becomes untenable.[5] Dissent provides the outline and substance of an alternative reading of the law and in some instances a speculative theory about the anticipated impact of the majority’s ruling on the lives of the public. Dissent on the Court is an act of critique, a speculative examination of potential implications, and an alternative conception of constitutional interpretation.

Speaking at a program for the American Bar Association, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in anticipation of the Court’s current session, “There is going to be a lot of disappointment in the law, a huge amount. Look at me, look at my dissents.”[6] But it is not the law that will be the source of disappointment for many of us, but the conservative Justices’ interpretation of the Constitution. Her dissents hopefully will appeal to the intelligence of a future Court and correct the errors to which not just the Court, but the people will be betrayed. Her provocative comments to the Bar Association about her anticipated dissents from the Court’s conservative majority suggest that the bench is ideologically stacked and the fix, if not entirely in, is more than halfway through the chamber door. She already knows (as do we), before the cases are presented, that she will be dissenting from the conservative majority on the major issues before the Court. She already knows how they will rule before they even hear the facts of the cases. Likewise, they know (as do we) how the liberal Justices will rule. It is hard to listen to Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Clarence Thomas, Justice Stephen Breyer, and Justice Samuel Alito’s recent defense of the Court’s objectivity without hearing Hamlet’s mother whisper, “The [justices] doth protest too much, methinks.”[7] Justice Sotomayor’s candor, however refreshing, simply acknowledges the elephant in the room long after most of us have been walking through its excrement.

Justice Barrett’s assertion that the justices are not a “bunch of partisan hacks” stands out amongst her conservative colleagues for its vernacular flourish and gritty indignation. Like Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s performance of teary eyed, rage-against-the-machine anger when questioned about sexually assaulting a woman in his youth, Barrett uses language more typical for a beat reporter or cop rather than what we might expect from someone representing the highest legal office in the country. Barrett and the others want to assure a skeptical public that they are above ideology and the partisanship that led them all by the nose to the Supreme Court in the first place.

Having laid down with dogs, she is determined to convince us that she and her colleagues have not come up with fleas. For Barrett and the rest of the Justices who feel the need to protest against the perception that they are, indeed, partisan hacks, the real partisan hacks are those lawmakers and political operatives in Congress and the Executive branch who demand ideological purity from their followers. Certainly, true for Trump and his inner circle, but also true now for the GOP more generally, the sycophantic expectation is part of the post-Trump GOP’s identity. But the problem for the protesting Justices is that the public isn’t as stupid as they think. People might not read the majority’s legal justifications for coming to one conclusion or another about a case before the Court. They might not get the finer points of law that the Justices labor to explain in their opinions and dissents. But they know when the Justices have decided a case in a way that aligns with their appointing President’s political biases. The people also know when their expectations of the Court and the Constitution are met or betrayed.

However perverted and compromised the Court was before Trump’s appointments and McConnell’s senatorial obfuscations, we have Trump’s vulgar disrespect for the rule of law, embrace of fascism, and willful ignorance of democracy to thank for pulling the veil fully back from the performance of judicial restraint. Like the mafia bosses of movie lore, Trump acts like he “made” those Justices he appointed to the bench and, as a sign of loyalty, they are expected to do what he set them up to do. For Trump and his flag-waving base, this quid pro quo relationship is uncontroversial. The Justices, Sotomayor notwithstanding, are the last ones to openly acknowledge what is apparent to everyone else. As the public shakes its collective head watching the Justices fall over each other trying to convince some of us that they are not partisan hacks hiding behind the judicial robes of blind justice, while trying to reassure their ideological constituencies that they can be depended on to rule as expected, carefully worded decisions and dissents spew forth from the ideologically divided bench that differentially shape and impact the daily lives of every person in the country.

The conservative Justices on the Court are mired in contradictions and disingenuousness, but to suggest that they are lying outright is maybe going a bit too far. What is at issue in these overwrought defenses of the Court’s objectivity is the process by which the Justices’ chosen method of constitutional interpretation over-determines outcome. Their “personal preferences” regarding abortion, gun control, campaign finance, free speech, the treatment of refugees and, more generally, freedom from governmental regulation vs. freedom by governmental regulation are hidden in plain sight in their choice of constitutional interpretative frameworks. Once the Justices’ decision has been defended on this or that ground, and the dissenting opinions are entered into the official record, the Justices are freed from the charge of ideological bias or political hackery.[8] They are simply following a methodological script, one that they spend a lot of ink defending for its ability to cut through the noise of partisanship in the other branches of government. Methods are not innocent; they are the tail wagging the dog.

The central question for the Court is not one about the Justices’ political bias, but whether they see the Constitution as a bridge that connects what is right to what is legal. If not, the authority of the Constitution to guide and constrain the Executive and Legislative branches as well as the Fourth Estate would be significantly curtailed. Questions of right and wrong would be relegated to philosophers and religion. The Justices, as Justice Roberts said, would just be calling balls and strikes, juridical umpires in the game of constitutional law. His comment begs the question as to whether the Court’s Justices should, at some point, be replaced by computers. Baseball is considering the move and tennis already made it. Why not the Court? If the Justices are only there to call balls and strikes then why the lifetime appointment, the endless hours of congressional questioning, the impressive educational bona fides, and reassurances that they are the best and brightest legal minds in the country?

Justice Robert’s comments do not hold up to even casual scrutiny. The Justices, both liberal and conservative, are doing more than calling balls and strikes. They are actively engaged in legal theorizing and constitutional interpretation. As such, they should be required to openly acknowledge whether they see the law and the Constitution as a moral signpost for our national human ecology. The Constitution, if it is to be able to carry the weight of its responsibilities, must be recognized for its ability to coherently address the unanticipated complexities of 21st century life in the United States. Once recognized as such a document, the Court must be overseen by Justices that have the intellectual ability to imagine the horizon of social justice as a beacon for their interpretations of the law. If not, then they shouldn’t be confirmed or even appointed. The question is not whether the Justices’ biases condition their reading of the law. The questions are: In the service of what kind of future do they imagine the Constitution supports and how do they plan to use their considerable power on the Court to prevent the “dogs of carnage” from ripping the gangrenous flesh of democracy from the republic’s brittle bones?

[1] Laetitia Zecchini and Karthika Naïr. India’s Season of Dissent: An Interview with Poet Karthika Naïr. https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/6651

[2] Grinberg-Schwarzer (2018). Understanding Glocal Contexts in Education: What Every Novice Teacher Needs to Know. Kendall Hunt. https://online.vitalsource.com/books/9781524972417

[3] Hon. Ruth Bader Ginsberg. Lecture: The Role of Dissenting Opinions., p. 4. https://www.minnesotalawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Ginsburg_MLR.pdf

[4] Ibid., p. 4-5.

[5] Erwin Chemerinsky. Justice Sotomayor tells the truth about the Supreme Court.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The creative hermeneutics employed by some of the more “liberal” justices to establish constitutional connections between what is legal and what is right might inadvertently reveal the moral limitations of the Constitution instead of its moral depth and reach. We know that just because something is legal doesn’t make it right. By the same logic, just because something is right doesn’t make it constitutionally defensible. This is one of the major differences between the “originalists” and the “living constitutionalist’s” approaches to constitutional interpretation. The latter work diligently and sometimes desperately struggles to find consistencies between what is legal and what is right within the broadening scope of the Constitution. Their work imagines a future that is fair and just and tries to find support for this utopic vision within the Constitution. The orginalists, by contrast, do not see the role of the Court to stretch the Constitution toward the moral horizons of justice or to mine it for moral-legal consistencies. The Constitution, for the originalists, is not the holy grail of morality that the “living constitutionalists” might have imagined. Although widely criticized as philosophically incoherent as well as intellectually limited, it has been easier to convince people that originalism is a more scientific (i.e., read “unbiased”) method of constitutional analyses than living constitutionalism.