by Usha Alexander

[This is the thirteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable Captain Picard has put it, “We’ve overcome hunger and greed, and we’re no longer interested in the accumulation of things.” Some Libertarian Trekkies have been scandalized to realize that Star Trek actually depicts a post-capitalist vision of society.

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable Captain Picard has put it, “We’ve overcome hunger and greed, and we’re no longer interested in the accumulation of things.” Some Libertarian Trekkies have been scandalized to realize that Star Trek actually depicts a post-capitalist vision of society.

But Star Trek’s world is premised upon the existence of a cheap, concentrated, and non-polluting source of effectively infinite energy. Obviously, no such energy source has ever been discovered (solar-paneled dreamscapes notwithstanding). And the replicator, which eliminates both material waste and scarcity, is a magical technology. The Star Trek vision is also a picture of human chauvinism and hubris, presuming H. Sapiens as the only relevant form of Earthly life. So it falls short of a vivid and plausible imagining of an ecologically sustainable, technologically advanced, and egalitarian human civilization.

It is, of course, too much to expect the creators of Star Trek, by themselves, to fully and flawlessly reimagine our global human society. Indeed, it’s become an aphorism of our age that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. Yet, though this might sound like a joke, at this point the matter is all too serious, and reimagining human civilization is a project we all must engage with, to whatever extent we’re able.

Expanding our imaginary of possible economies, social structures, value systems, and more is an urgent matter as our present way of life is driving the catastrophic collapse of the biosphere, potentially precipitating the demise of humankind. In this context, we have everything to gain by risking new courses, which might offer a better chance for ecological balance and survival. And as our suicidally extractive, fossil-fueled civilization comes to an end, we must finally answer the question: What will we build in its place? Can we build a world more caring, more just, more sustainable?

To manifest any desired outcome, one must first imagine it: a real and vivid world—not a utopia, but a human world—in which fairness, generosity, cooperation, and care are the animating values that guide collective human behavior and social institutions. We know such a vision is possible—without the simplification and sanitization of Star Trek—because these values really did guide some of the most ancient social orders that actually existed, including those that predated the rise of city-states and promoted human flourishing for the greater part of our time on Earth. Indeed, rather than starting from science fiction, we might recognize our past might point the way, with real-world principles—or at least inspiration—for imagining alternate economies and social structures that can further enable human flourishing through the challenges of climate instability, which has so long shaped the human story.

Value Games

We say “money makes the world go round,” but the world was not still before money was invented, only a few millennia ago. We’re now obsessed with amassing money almost as an end in itself, or as a means to purchase an ever-expanding array of consumer goods. I remember when, as a child, a snow-globe depicting an exotic scene, like the New York City skyline, was a wonder and a small treasure. The snow-globe’s moment of glory didn’t last long though; such trinkets soon became overly ubiquitous and lost their charm. Soon, there was too much of everything. Over the last half-century, most of the petrochemical-derived novelties we once briefly prized have become so cheap and ordinary that they no longer hold any value at all. They pile up as rubbish, unloved, disposable. Particularly in the United States, where acquisition has become something of a social disease, people want bigger houses and garages and storage spaces only to mount their piles of junk, much of which they don’t use or even look at for years. Increasingly, it seems we identify wealth with our rate of consumption of what’s ordinary and replaceable. We buy the latest clothes and gadgets and appliances, disposing of what’s no longer current or amusing or cool, creating a steady pipeline from production to waste. We could well say that a good indicator of a nation’s wealth is the waste it generates, that rubbish makes the world go round.

But human societies have subscribed to many other conceptions of value. Looking at other value systems might just shake us out of our capitalist stupor and help us remember that alternatives are not only possible but very much normal. Indeed, prior to the rise of monetary economies, the world spun on a different principle altogether, when all peoples primarily practiced some form of a gift economy. Though these ancient economies may have also incorporated market systems, including barter and exchanges mediated through items that share features in common with money, it was gift-giving that made their world go round. Gift economies operate according to logics that may seem bewildering to us, constrained as we are by our capitalistic imaginations, so that we find them bizarre and obtuse. But this is as much a reflection of our limitations as outsiders to alternative systems as it is a testament to the astonishing breadth of human possibility. More than anything, however, the variety, ubiquity, and prevalence of gift economies among human societies remind us that our conventional narrative of economic systems as rational systems of goods-exchange, in which capitalism is seen as the efficient culmination of inevitable human propensities, is almost as simplistic as the economic vision of Star Trek.

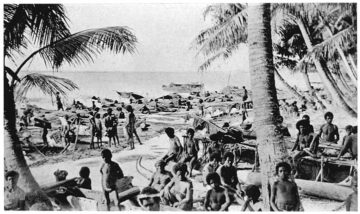

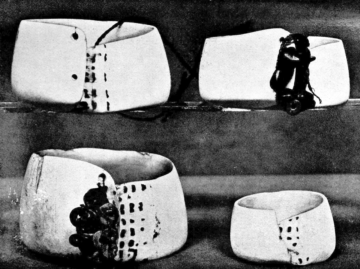

Consider, for example, one well-documented example of a gift economy, known as the kula ring. This elaborate system of exchange drives the economy of the Trobriand Islands, a ring of tiny islands in the Solomon Sea. At its center are kula objects, necklaces and armbands, made from decorated seashells, which are competitively gifted in events of great ceremony, tradition, and ritual that take place a few times a year. Kula objects are almost never worn nor are they valued for their utility. Rather, analogous to the way, say, the Hope Diamond or an original sketch by Michelangelo are highly treasured in our society, despite having no practical use, so it is with these kula objects: each object derives its individual value in part from its particular beauty, but also largely from historical sentiment, its unique story of creation or association with something noteworthy in the past, like prestige or magic or death. But beyond that, the system takes on more peculiar aspects: The gift of an armband must be answered with a return gift of a necklace, after a socially appropriate span of time. Armbands may only be given to individuals on islands located in a counterclockwise position from one’s own, along the ring of islands, and necklaces can only be given in a clockwise direction. Individuals who exchange kula gifts are wedded into a lifelong relationship of gift-giving, with no socially sanctioned exit. It’s mostly men who “play” kula, though much of their wealth is derived through the auspices of the women in their families, who may be politically and economically powerful in their own right. The number of trading partners a man has is a matter of great social significance, with some having as few as two or three partners and a chief or headman having potentially hundreds.

Consider, for example, one well-documented example of a gift economy, known as the kula ring. This elaborate system of exchange drives the economy of the Trobriand Islands, a ring of tiny islands in the Solomon Sea. At its center are kula objects, necklaces and armbands, made from decorated seashells, which are competitively gifted in events of great ceremony, tradition, and ritual that take place a few times a year. Kula objects are almost never worn nor are they valued for their utility. Rather, analogous to the way, say, the Hope Diamond or an original sketch by Michelangelo are highly treasured in our society, despite having no practical use, so it is with these kula objects: each object derives its individual value in part from its particular beauty, but also largely from historical sentiment, its unique story of creation or association with something noteworthy in the past, like prestige or magic or death. But beyond that, the system takes on more peculiar aspects: The gift of an armband must be answered with a return gift of a necklace, after a socially appropriate span of time. Armbands may only be given to individuals on islands located in a counterclockwise position from one’s own, along the ring of islands, and necklaces can only be given in a clockwise direction. Individuals who exchange kula gifts are wedded into a lifelong relationship of gift-giving, with no socially sanctioned exit. It’s mostly men who “play” kula, though much of their wealth is derived through the auspices of the women in their families, who may be politically and economically powerful in their own right. The number of trading partners a man has is a matter of great social significance, with some having as few as two or three partners and a chief or headman having potentially hundreds.

In the subsistence economy of Trobriand society, food and other utilitarian items are regularly distributed through gift-giving within one’s own family, lineage, clan, or village, based on prescribed social obligations. For instance, a man is required to give his taro crop to his wife’s brother; this expectation is enmeshed in a tangled web of obligations that ensure the giver will himself never want for taro—or anything else he needs. However, peace, security, and mutuality between clans, villages, tribes, and islands are regulated by the kula ring economy: Throughout the year, labor is arranged for building canoes, under the auspices of upcoming kula expeditions. Gifts of food—pigs, taro, bananas, coconuts, sugar cane, and other relatively storable consumables—as well as occasional tools and utensils are given to those with whom one is bonded in a kula relationship or help support one’s kula obligations and aspirations. Food is collected, enticingly displayed, and shared, given away, or bartered at various stages of the game, up to and including the culminating ceremonies. Feasts and giveaways redistribute food and goods to the laborers and expert consultants involved in canoe building, as well as to those who help with provisioning, harvesting, and transporting of food stocks. While any of these activities could be carried out without anything to do with the coveted kula objects, in the minds of the Trobriand participants, it’s the kula gifting that regulates social power across the islands, giving sense, meaning, fairness, and legitimacy to the rest, as much as any economic ideology or system of laws. Attainment of the most valuable kula objects is an achievement of merit and sociopolitical power. Meanwhile, the overwhelmingly complex subsidiary exchanges that support the kula ring are but everyday activities that habitually conform to its logic and meanings.

The kula ring makes the Trobriand world go round, ensuring peace, stability, and regulatory patterns for inter-island, inter-village, inter-clan exchange, carried out through multiple subsidiary and parallel gifting and bartering transactions, including access to rarer resources that are uniquely found within the domains of particular tribes, such as certain shells or animals. While the belief system around the kula plays a role in the organization of certain forms of labor and regulates the provisioning and transport of food and other utilities, Malinowski, the anthropologist who first documented the kula ring, tells us the participants in the system don’t themselves think in top-down terms of the greater “kula ring economy,” the abstract parameters of which he deduced from his highly detailed observations of everyday life, any more than we think about supply and demand or production efficiencies and international trade alliances when we buy a box of cereal from a chain supermarket. Nor is the clockwise/counterclockwise, necklace-for-armband ring of exchange a slate of laws or a conceptual design, but rather a kind of emergent phenomenon, arising from the participants’ everyday activities and beliefs about appropriate behaviors and their personal goals. The islanders don’t worry themselves about the causal link between their daily and yearly cycles of giving and receiving gifts, barter, social and economic power and how these create the kula ring; they’re just doing their best to perform within their own social contexts.

The complex rules of the exchange—who is entitled to exchange with whom, and precisely what those exchanges convey in terms of status, prestige, and mutual obligation—will be opaque to us, who are unfamiliar with its particular system of values and meanings and underlying magical beliefs. But kula is their story, as much as the Invisible Hand of the Market is ours. Malinowski emphasized that, like us, Trobriand Islanders are also enamored of great wealth, which for them takes the form of high-quality produce, fine pigs, and kula objects. But an essential difference between their society and ours is that their signaling of wealth comes neither through hoarding nor the rapid and ostentatious consumption of it, but rather in the ostentatious gifting of it, giving it away or sharing it. To this end, islanders expend their energies with a zeal, commitment, and competitive spirit similar to that with which we’re urged to work for our corporate boards and shareholders.

The complex rules of the exchange—who is entitled to exchange with whom, and precisely what those exchanges convey in terms of status, prestige, and mutual obligation—will be opaque to us, who are unfamiliar with its particular system of values and meanings and underlying magical beliefs. But kula is their story, as much as the Invisible Hand of the Market is ours. Malinowski emphasized that, like us, Trobriand Islanders are also enamored of great wealth, which for them takes the form of high-quality produce, fine pigs, and kula objects. But an essential difference between their society and ours is that their signaling of wealth comes neither through hoarding nor the rapid and ostentatious consumption of it, but rather in the ostentatious gifting of it, giving it away or sharing it. To this end, islanders expend their energies with a zeal, commitment, and competitive spirit similar to that with which we’re urged to work for our corporate boards and shareholders.

The kula ring economy is practiced by settled peoples inhabiting small Pacific islands, among which some, though not all, of the tribes submit to a narrow degree of political stratification; yet even among tribes with fixed hierarchies between their clans or lineages, disparities in subsistence levels don’t exist to any degree remotely approaching what’s regularly seen in capitalist systems. The kula ring economy is a demonstration that economic systems—from what we perceive as wealth to the dynamics of its circulation and even how its value is manifest, whether as coin or rubbish or formal obligations and privileges—like all other human social constructs, are built more from the rationales of shared stories than from rational assessments of the utility of the items being exchanged. And gift economies have been far more common throughout the human story than hoarding economies, which only overtook the world not five centuries ago.

We might contrast market and gift economies by noting that in market economies, once an item is sold for a price deemed fair by the Market, all rights to the item revert to the owner and the seller relinquishes all claims. The commodity itself is understood to be separate from the seller, absolutely alienable not only in terms of its economic value, but also in terms of its communal value. Thus, individuals are perfectly free to sell, hoard, financially profit from, or waste whatever resources they own in a system of largely unfettered autonomy. One can even buy a treasured sketch by Michelangelo and burn it. And whatever we do with our wealth, it is detached from the needs of our neighbors.

By contrast, any of these prerogatives may or may not be available, to varying degrees, in the various exchanges that occur within different gift economies. Gift economies are generally characterized by webs of social relationships, rights, and obligations. Gifts are not viewed as mere commodities, but as signifiers of meaning and sometimes as vehicles of various prescribed entitlements and responsibilities. There may be rules about what can or must be given to whom, and when. When an item is given, the giver may retain certain claims to it, so that the notion of “property rights” is not whole and absolute, but may be divisible along layers of meaning. In the kula ring, aspects of social rank, prestige, and kinship solidarity are implied in every exchange. And while each player seeks to possess the most valuable necklaces and armbands available to him, gaining possession of a prized item doesn’t necessarily mean he owns it.

In gift economies, durable items of value are expected to keep actively circulating, changing possession within whatever is considered a socially appropriate timeframe in a given system. For example, no kula object can be kept out of the gifting circuit for more than a year or two without its keeper suffering socially injurious recriminations; to not re-gift it is damaging to the economy. In other gifting systems, any possession of yours that another person openly admires must be given to them; it’s unthinkable that you would refuse to make a gift of your treasures—of course, the expectation goes both ways. Hoarding or accruing items of value is generally proscribed or at least made exceedingly difficult by the rules of the game. There are implied reciprocities contained in every exchange. But whether these are specific or a more generic expectation of a communal or individual “return gift” of unspecified value to be given at an unknown future date, exchanges can’t be reduced to mere financial equivalence; instead, they invoke degrees of social indebtedness and ritual or practical meaning. The bonds inherent in gift-giving often extend even to the non-human world, so that, for example, when a salmon is seen to give its life or a strawberry share its fruit for your sustenance, you understand yourself meaningfully connected and reciprocally indebted to it, perhaps obligated to propagate its progeny or provision its kin. In a gift economy, nothing given is rubbish, nor is it free. The only profit to be made is social. And nothing belongs quite entirely to any individual, at least not in perpetuity.

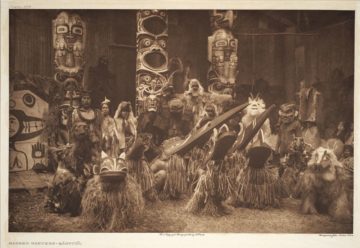

Needless to say, gift economies have not created utopian societies any more than anything else of human devising. It takes little to imagine the various politics of resentment that heavy yokes of social obligation might engender in some individuals or circumstances. In some cases, gift-giving has even been known to evolve into excessive wealth redistributions resulting in wastage, as has been seen in certain potlatch ceremonies. The potlatch is an economic form once common among Indigenous communities along the northwestern coastal region of North America, in which the leaders of local kinship groups collected wealth—typically in the form of fresh and preserved food, canoes, copper, animal skins, other such goods, and sometimes even slaves—for the purpose of giving it all away. Potlatch giveaways typically take place on the occasion of a great feast, like at the birth of a child, or in affirmation of changing relationships or spiritual connections. The host who is able to amass—through politicking, persuasion, and gift-giving/indebting others to himself—and then redistribute the greatest amount of wealth, enjoys enormous social stature. In some instances, the gift-giving became excessively inflated, until the potlatch featured such an amount of goods that the successful host proudly destroyed the excess; it’s never to be kept for personal use. In some communities, potlatch giveaways were hosted only by the leaders of the highest status lineages, competing amongst themselves to rack up and defend their considerable social capital. This concentrated social power in particular kin groups, while excluding certain others from effectively competing, thus entrenching a degree of social stratification. Yet even in such cases, this resulted in far less economic disparity than what we regularly see in capitalist economies. Nor did all forms of the potlatch system even lead to such heady extremes. And other mass giveaway economies, like the moka of Papua New Guinea, lead neither to such wastage nor entrenched hierarchies.

Needless to say, gift economies have not created utopian societies any more than anything else of human devising. It takes little to imagine the various politics of resentment that heavy yokes of social obligation might engender in some individuals or circumstances. In some cases, gift-giving has even been known to evolve into excessive wealth redistributions resulting in wastage, as has been seen in certain potlatch ceremonies. The potlatch is an economic form once common among Indigenous communities along the northwestern coastal region of North America, in which the leaders of local kinship groups collected wealth—typically in the form of fresh and preserved food, canoes, copper, animal skins, other such goods, and sometimes even slaves—for the purpose of giving it all away. Potlatch giveaways typically take place on the occasion of a great feast, like at the birth of a child, or in affirmation of changing relationships or spiritual connections. The host who is able to amass—through politicking, persuasion, and gift-giving/indebting others to himself—and then redistribute the greatest amount of wealth, enjoys enormous social stature. In some instances, the gift-giving became excessively inflated, until the potlatch featured such an amount of goods that the successful host proudly destroyed the excess; it’s never to be kept for personal use. In some communities, potlatch giveaways were hosted only by the leaders of the highest status lineages, competing amongst themselves to rack up and defend their considerable social capital. This concentrated social power in particular kin groups, while excluding certain others from effectively competing, thus entrenching a degree of social stratification. Yet even in such cases, this resulted in far less economic disparity than what we regularly see in capitalist economies. Nor did all forms of the potlatch system even lead to such heady extremes. And other mass giveaway economies, like the moka of Papua New Guinea, lead neither to such wastage nor entrenched hierarchies.

Gift economies have been documented in mind-boggling variety. Another type, altogether, is found among very egalitarian societies, in which essential resources are broadly shared; non-consumable valuables regularly change hands; and rights to immovable property or long-term productive resources (for example, fishing access to a particular lake) are held in some form of cooperative or joint tenancy. But what gift economies seem to have in common is that they aren’t driven by the motive to accrue personal financial profit but rather, by the desire to gain wholly different social rewards. And they are frequently guided by values of social cohesion, care, generosity, and fairness. Of course, as in any other human economy, some participants are corrupt; some cheat. But on the whole, gift economies glorify cooperation over competition. They provide adequately for everyone in the community, leaving no one in a state of want and no one with far more than they need. And, at least until the time they encountered the spread of mercantilism and statism, gift economies were bounded by local ecological limits, the carrying capacity of the land. The continuous redistribution or sharing of local wealth, disallowing any hoarding of great surpluses, meant the system would have remained closely tied to the land, allowing little scope for overshooting its limits. Even a social hierarchy that was growing heavier on the back of inflationary giveaway feasts could only develop and persist up to a point, as the intensity of resource extraction it required approached the limit beyond which its participants could no longer reliably produce and supply goods into the system. One can imagine that some inflationary societies did occasionally approach or even hit the local ecological limits, such that their existing class or caste systems fell away to be replaced by a new slate of aspirants.

Market (monetary or barter) and gift economic systems might be seen to exist on a continuum, perhaps multi-dimensional, so that no society purely participates in only one type of economy or the other, and neither can every exchange be classified purely as a gift versus a trade or sale. It seems likely there’s some optimum blend of gifting and market exchanges that best serve members of any given society, individually and collectively, which surely depends upon the particular needs of the people in their particular environment and the mix of locally available goods and services. But today, though the kula ring, the moka, the potlatch, and other gift economies still function in Indigenous communities across the world, all of them have been eroded or corrupted by the introduction of fiat money and foreign goods through expanding market economies, usually associated with widening socioeconomic disparities and ecological degradation.

Market (monetary or barter) and gift economic systems might be seen to exist on a continuum, perhaps multi-dimensional, so that no society purely participates in only one type of economy or the other, and neither can every exchange be classified purely as a gift versus a trade or sale. It seems likely there’s some optimum blend of gifting and market exchanges that best serve members of any given society, individually and collectively, which surely depends upon the particular needs of the people in their particular environment and the mix of locally available goods and services. But today, though the kula ring, the moka, the potlatch, and other gift economies still function in Indigenous communities across the world, all of them have been eroded or corrupted by the introduction of fiat money and foreign goods through expanding market economies, usually associated with widening socioeconomic disparities and ecological degradation.

Of course, not many of us are ready to jettison the world we know in order to embrace social and economic systems based on values and meanings entirely alien to us. Enamored as we are of efficiency, growth, and nearly absolute individual autonomy, we fear systems that we might perceive as more encumbered. In any case, there is no possibility of recreating any specific systems of the past, even should we wish it. That world is gone: geophysically, geochemically, biologically, ecologically defunct and changing. But knowledge of what our ancestors have already experienced, understanding and considering the principles by which alternate systems have worked may best expand our imaginary as we explore new possibilities for a sustainable and more just future civilization. It is vital to remind ourselves that capitalism is not a natural law of human affairs; there were systems that predate it and there are systems that will follow it. Fortunately, there are a handful of thinkers and doers today who are attempting to build at least pockets of such societies by trying to envision new modes of social and economic functioning based in our modern knowledge systems and material realities.

The Profit of Not Profiting

The Catalan Integral Cooperative (CIC) is a post-capitalist social network that’s been functioning throughout Catalan, Spain since 2010. Structured as a decentralized web of dozens of autonomous collectives, societies, and committees engaged in technical work, creative pursuits, legal and social services, farming and food production, and more, it includes many of the activities that keep a modern society humming. The members of this integrated network of cooperatives share a vision for social transformation, and the CIC coordinates the provision and exchange of their various goods, services, and knowledge transfers. Their financial transactions are funded through Euros, “eco” (their own “social currency”), cryptocurrency, and possibly barter. Anyone can participate in the activities of the CIC or an associated cooperative, as a worker or a consumer.

Spurred into existence by the pro-Catalan (anti-Spain), activist sensibilities of the Catalan people in the wake of the socioeconomic austerities foisted upon them by the Spanish government during the 2008 global economic crisis, by 2010 the CIC already employed hundreds of people and engaged upwards of twenty-five hundred participants, who make use of its networks (current data about its activities and results is, unfortunately, difficult to find). Its goal isn’t only to support the wellbeing of its members and participants, but to bring about the “‘creative destruction’ of the capitalist system” (1), according to political scientist George Dafermos. In keeping with this, all of their knowledge production is open-source—not just software, but including any tools or machines its members invent, for example, those meant to help small farmers or artisans. Through its capitalist-subversive practices, the CIC aims at nothing less than social transformation, based on principles in line with egalitarianism and justice, mutual support and sharing, degrowth and ecological sustainability. Though ensconced within the capitalist entity of the Spanish state, the CIC nevertheless strives toward degrees of economic autonomy to the extent possible.

Though the Catalans haven’t created a utopia, that needn’t be the measure of their success; after all, our techno-capitalist reality continuously fails by that yardstick too. And while it is silly to expect any sociopolitical or economic arrangement to live up to an inhuman ideal, it is not silly to aim for sustainable human flourishing, nor to build a society more resilient to shocks like those arising from climate change.

The CIC is an example of a functioning collective that’s imagining alternate sociopolitical modes, which might even prove more resilient and sustainable on our changing planet. In maintaining decentralization of resources, local autonomy, bottom-up governance, and bio-regionally sensitive extractive practices, it appears to align with several principles also found in sustainable gift economies (2). It might just represent an imaginative step toward the kind of distributive economy that economist Kate Raworth prescribes as one aspect of a sustainable system, one in which wealth and production are decentralized not merely through taxes and wealth redistribution, but systemically, by design (3) (gift economies share this feature, though they may additionally redistribute wealth). Its activities may also allow for not-for-profit business models, such as have been gaining presence within the larger capitalist economy, in which profit is sought not as its own reward, but only as a means to funding a larger goal for a whole community (4)—sharing a company’s accumulated largesse, an echo of mass giveaway traditions.

What these visions, ideas, and models may have in common is that they tend to promote reduced consumption, compared to the presently unsustainable indulgence of the world’s wealthiest ten percent (which includes the global “upper-middle class” and most inhabitants of Western nations). They shift the goals of technological innovation by funding projects that address the needs of the collective and benefit more or most people within their community, while defunding projects that primarily benefit a minority at the expense of others (privileging notions of liberty for a few, while ignoring wage slavery and worse for the rest) or that spoil the commons in the long-term. They demand fewer hours of impersonal work and produce slower, community-oriented patterns of life with no easy avenues for mass wealth accumulation and much flatter hierarchies of social and political power, compared to our modern global society. They’re fundamentally built upon values of equitability, cooperation, and care. Taken together, these visions of transitional or post-capitalist economies echo pre-capitalist social and ecological values, bearing traits of gift economies, if not consciously or completely.

And none of these consequences seem terribly disagreeable, in terms of quality of life. Yet, because reducing consumption and working hours will reduce GDP, leading to economic de-growth rather than growth, they strike fear in the hearts of those constrained by capitalist narratives and wedded to present power structures, who don’t wish to imagine the end of capitalism. However, among those investigating the present ecological overshoot of the human enterprise, degrowth is commonly understood as necessary. There’s no honest framing of our present ecological condition that allows for expansion or even the steady state of the present size of the human enterprise; whatever fears degrowth inspires, its consequences will be far less adverse than the alternative. Having already overshot several of the planetary boundaries for maintaining a healthy biosphere, degrowth is inevitable, whether it’s more managed or catastrophic, whether it’s voluntary or disastrously thrust upon us by our future circumstances.

According to economic anthropologist, Jason Hickel, when intentionally undertaken and managed, a program of degrowth is “a planned reduction of aggregate resource and energy use in high-income nations designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a safe, just and equitable way” (5). Growth in the Global North, he explains, relies upon massive extractions of materials and energy from the Global South, moving billions of dollars of wealth toward the wealthy, in contemporary relationships that recreate patterns of colonial exploitation. But those resources are justly required to meet the needs of the Global South.

Economic degrowth would perforce result in substantial lifestyle changes, commensurate with the exclusion of fossil fuels and petrochemicals from our patterns of material consumption. It would cause value systems and social institutions to shift and reconfigure. It requires a recalibration of geopolitical power dynamics and social justice. Degrowth isn’t amenable to capitalism nor can it be reduced to 20th-century anti-capitalist responses, such as communism or socialism, which also rely upon growthist paradigms (differing mainly in who owns the means of production). But neither is degrowth a program of enforced scarcity. Rather, it’s a just distribution of resources and an intentional reduction of material use by over-consumers that arises from an altogether different paradigm of understanding, one that places humanity in balance with the non-human world.

Mainstream criticisms of degrowth tend to fixate on GDP, as though it were a measure of human wellbeing, though everyone knows it isn’t. Or they push the dream that economic growth can be strongly de-coupled from resource extraction and pollution, because it has recently shown a weak decoupling in some nations. But there’s no charted path to significantly increase decoupling. Critics may wave their hands and suggest increasing efficiency of resource use might do the trick, though Jevon’s (so-called) paradox shows that this tends to increase resource use in a capitalist system. Grasping at such ecologically disconnected fantasies only makes such critics appear afraid to admit the loss of privilege to hoard resources in the Global North, over-consume among the wealthiest ten percent, and maintain the present, capitalist status quo. Yet even the staunchly conservative IPCC is coming to acknowledge the degree to which any meaningful answer to our present ecological crisis requires a radical shift from where we are now to alternate economies and social modes; in fact, a leaked version of their upcoming report accedes that the capitalist model of economic development is “unsustainable”.

The perversions of capitalism, its glorification of competition and hoarding, have already brought our system to a state that encourages what economist Herman Daly called uneconomic growth, in which the costs of technical innovation outweigh the gains, because the dynamics driving it favor benefits to individual wealth for a handful of players with absolute disregard for the broadly shared social and environmental costs. Several writers have already diagnosed our condition as having entered a phase of disaster capitalism, in which capitalists profit from public fear and misfortune, sometimes caused or exacerbated by the profiteering class, themselves—for example, through the sale of vaccines during a pandemic; or aid, when climate change fuels fires and floods and wars; or security services, as crime rates rise with poverty. But, in fact, if capitalism isn’t abandoned, it’s likely to enter a stage that political scientist Craig Collins calls catabolic capitalism, eating whatever social gains have until now generally been attributed to capitalism, as our planet’s ecological systems further degrade. When capitalism turns catabolic, disaster capitalism extends itself and joins anti-social entrepreneurship—like dealing in slaves, arms, and drugs—to become the central pillars of economic growth.

How can we choose this for the human future, when we could choose an alternative? The ordinary economic systems of the past offer promise that more egalitarian and cooperative social and economic modes can arise, given the chance. Indeed, if economies based on glorification of sharing and cooperation (versus hoarding and competition) functioned at scale, resulting in new conceptions of value, where social good and personal prestige became the form of profit that replaced monetary profit, it’s easy to imagine new economies emerging, far different from what we today believe as the default, imbuing at least some transactions with the flavors of a gift economy. And if this notion was again extended to the non-human world, as it once had been, this shift could be a balm that helps heal the presently ailing human relationship to the rest of the biosphere. Are such systems beyond rediscovery today? Or could a society based on timeless, essential human values, coupled with modern knowledges, be reimagined to produce a civilization more viable than this one?

Of course, at present, none of these pre/post-capitalist ideas or enterprises are fully functioning even at the scale of a small nation. Given the political resistance and ongoing failures of imagination, nor do I claim to see nations voluntarily moving from where we are now to full implementation. But the strongest hope I have for the human future is that we’ll manage the decline and transition of our present civilization in a way that ultimately promotes greater equality and sustainability. As we are forced to imagine the end of the world, people are struggling to imagine the end of capitalism. Organized groups are attempting to re-envision sustainable enterprises rooted in knowledge sharing, a more egalitarian ethos, and active opposition to the hoarding of wealth and socioeconomic hierarchies, bearing echoes of functioning systems from our long human past. Particularly in South and Central America, several Indigenous movements are well underway to restore local sustainability and equitability.

For now, these conceptions remain only as seeds and sprouts, the beginnings of a new imaginary that is yet to be fleshed out by practice and circumstance, as the world changes. But while mainstream capitalist culture tells us that its own social dynamics are inevitable or hard-wired into human nature, we might heed the existence and appeal and promise of emerging post-capitalist visions, alongside ample evidence from prehistory and the living narratives of many Indigenous peoples, which remind us that this is simply not so. It’s here that I find hope.

[Part 14: Toward a Polyphony of Stories. All essays in this series can be found here.]

Notes:

1 George Dafermos, The Catalan Integral Cooperative: an organizational study of a post-capitalist cooperative, 2017.

2 Several of these principles are outlined in architect Joe Brewer’s recent work, The Design Pathway, though he doesn’t speak about them explicitly in terms of gift economies. Brewer works with Indigenous peoples in Colombia to help create bio-regionally sustainable societies.

3 These are described in analytical detail in How on Earth: Flourishing in a Not-for-Profit World by 2050, by scholars Jennifer Hinton and Donnie Maclurcan.

4 Hickel, J., & Hallegatte, S. (2021). Can we live within environmental limits and still reduce poverty? Degrowth or decoupling? Development Policy Review, 00, 1– 24. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12584.

5 For more on this, one possible introduction is The New Possible: Visions of Our World beyond Crisis, edited by Philip Clayton. 2021 Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Images

1. Captain Picard, Dr. Pulaski, and Commander Riker enjoy an array of interplanetary delicacies produced by a replicator in the Ten Forward lounge of the USS Enterprise. Screenshot from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Fair use.

2. A kula gathering on a Beach of Sinaketa. On this day, over eighty canoes arrived for the event, parked along a half-mile stretch of the beach. The crowd of participants and spectators numbered some two-thousand people from at least five separate tribes. Photo by Bronislaw Malinowski, prior to 1922. Published in Argonauts of the Western Pacific. George Routledge & Sons, Ltd. 1922. Public domain.

3. A set of mwali, or “armbands,” used in the kula ring economy of the Trobriand Islands. Photo by Bronislaw Malinowski, prior to 1922. Published in Argonauts of the Western Pacific. George Routledge & Sons, Ltd. 1922. Public domain.

4. Kwakwaka’wakw dancers, of today’s British Columbia in Canada, performing at a potlatch ceremony, circa 1900 CE. Photo by Edward S Curtis. Public domain.

5. A modern-day veigun or soulava, or “necklace,” used in the kula gift exchange, circa 2000 CE. This one features glass or plastic beads, which would not be a local item of production, demonstrating the intrusion of foreign goods and markets into the kula economy that operates today, and how it has drifted from its local, ecologically-moored origins. Photo by Brocken Inaglory. Creative Commons.