by Dwight Furrow

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Today, few philosophers believe philosophy is a way of life, let alone the fullest and most complete way of life. Or if they do believe it, they won’t admit it in public. Only a handful of scholars, those studying ancient Greek ethics, have much to say about wisdom. Few think the question of the best human life has an answer, and if philosophy is a way of life, it consists of trolling rivals at department meetings and writing journal articles for an audience of ten specialists.

The scandal is not that modern life has moved on from issues the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought were important. Surely, the question of how one ought to live remains a pertinent question for anyone to ask. The scandal is that philosophy no longer thinks of itself as providing a guide to life and seems unconcerned about this. The question we fear most coming from non-academics is “What is your philosophy of life?” In public, the question is met with embarrassed silence. In private, it is a source of mirth and derision that someone is so jejune as to think such a thing is something philosophers ought to have. Read more »

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face?

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face? When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

When Robert Solow asked me in Cambridge if I’d like to join the faculty at MIT in the other Cambridge, I was taken aback, and asked for some time to think about it. Until then I never imagined living in the US, a country I had never visited before, and what I saw in Hollywood films was not always attractive. I was planning to go back to India where my aging parents, younger siblings, and the majority of my friends were.

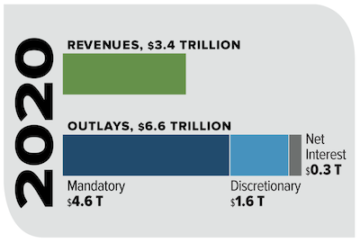

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide.

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide. Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”

Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”  Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.