by Omar Baig

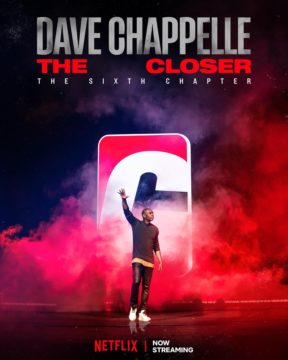

Dave Chappelle grapples with the intractability of gender norms in The Closer: his most recent and final stand-up special for Netflix. Early into the set, Chappelle recounts the one-sided fight he had at a nightclub with a lesbian woman. When she interrupts his conversation with a female fan, Dave assumes they’re a jealous boyfriend. He deescalates the situation, however, once he realizes they are actually a jealous girlfriend; yet his unintentional misgendering only antagonizes her more. She reacts by squaring up in “a perfect southpaw stance” and throws the first punch. Chappelle reflexively dodges, then reacts in kind, by knocking “the toxic masculinity” out of her.

This, ladies and gentle-folx, is Edgelord comedy at its spiciest. Now, was it okay for Dave to misgender this woman, even unintentionally? No. Did Chappelle have to respond by, “softly and sweetly,” telling her: “Bitch, I’m about to slap the shit out of you!” Also, no. Yet was he justified in “tenderizing those titties like chicken cutlets,” in self-defense, once she threw that first punch? In my opinion, yes. This anecdote illustrates that toxic masculinity, like public acts of jealousy or public aggression, is not only limited to men. It also features two of The Closer’s recurring motifs: (1) Dave’s respect of others as reciprocal to their respect for his personal boundaries (i.e., irrespective of sexual or gender identity); or (2) by all the ways that performing informs his personal, social, and creative interactions.

Since returning to stand-up in 2013, Dave seems more paranoid than ever of becoming a moving target: liable to character assassination or career cancellation at any moment, from all directions. And for good reason: the woman that swung first, for instance, later tried (and failed) to sell her story to TMZ as a hate crime. In the last four years, Chappelle has faced sustained backlash from both the LGBTQ+ community and his own fans for his homophobic and transphobic material. As an outspoken artist, he has built his reputation as a comedian who strives to speak truth to power—without having to “punch down” on the powerless for a cheap laugh. Dave’s pride and ego, however, appear noticeably wounded throughout The Closer.

I can feel the heaviness as he mourns his friend Daphne, despite the disrespectful barrage of transphobia that precedes it. Although neither Chappelle’s endorsement of trans-exclusionary feminists like J.K. Rowling, nor his claim of being on #TeamTERF, helps my case, I still don’t believe Dave Chappelle fully crosses the line from transphobia to hate speech. In his defense, The Closer takes time to condemn legislative bans against trans people from using public facilities. Chappelle argues that North Carolina’s ban on transgender or non-binary people from using public restrooms that do not correspond to their assigned sex is both needlessly cruel and irrational.

Performing Gender

Trans-exclusionary feminism centers on the politics of having a vagina, giving birth, or being sexually assaulted by men. As a Black man, Dave Chappelle can sympathize with TERFs pressured to include trans women in their feminist movement. He even likens their antipathy to a Black person offended by a White person in black face, as participating in a parallel form of gender appropriation. Chappelle doubles down by declaring that gender is a fact, since everyone must pass through the legs of a woman to exist. Except that trans men can, and do, give birth. This “fact” ignorantly restricts gender expression, by privileging the reproductive properties of biological sex.

In their seminal 1990 book, Gender Trouble, Judith Butler examined how the stylization of the body reflects gender identity: “and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds make up the illusion of an abiding gendered self.” Thus, gender entails both a biological, or reproductive, basis and a constituted social temporality. In a recent interview, Butler notes that “none of us totally escape cultural norms”—“people are, consciously or not, citing conventions of gender,” especially when “expressing their own interior reality” or by saying that “they are creating themselves anew.” Earlier this year, Butler remarked on J.K. Rowling’s views on TERFs: “It’s terrible that she chose to make these views public,” without working “them out in a less public venue.”

While sympathizing with Rowling’s traumatic history, Butler argues, “that of itself does not mean that all men are rapists, or that the penis wields this nefarious power on its own.” By fostering, even unintentionally, “hatred and misunderstanding,” Rowling has “not used her public position well.” “It is, in general,” they conclude, “a responsibility not to pass on your trauma.” Dave Chappelle, I argue, has also failed to uphold this responsibility. He of all people should appreciate another person’s right to perform on their own terms. Chappelle does, however, support certain trans people—at least when they “perform” on his terms. The Closer, for example, ends by memorializing Daphne Dorman, a devoted fan and transgender woman he invited to open his sold-out shows in Oakland.

Dorman’s unwavering support, despite all the attacks she subsequently faced from her own community, deeply moved Chappelle: who celebrated Daphne’s natural gifts as a performer who fed off the crowd and could improvise a clever comeback—without letting a heckler ruin her stand-up set. Dave, however, took another approach to a trans woman he runs into at a local bar. When she refuses to perform in his awkwardly public peace offering—by reiterating how his comedy “punches down” on her as a trans woman—Chappelle turns to the two gay Black men whom accompany her as friends, as if to ask: “Is there anything you two n***** need to tell this bitch” about what it’s really like to be oppressed?

Will the Real Philosopher-King or Queen Please Stand Up?

While Chappelle’s generosity towards Dorman’s surviving daughter is commendable, I still wonder how Dave, as a proud Black man, failed to anticipate how his celebration of Dorman recasts her as a trans-martyr or casualty of “cancel culture” run amok. He resents any ideology that preemptively stops our neighbors and citizens from having real, face-to-face conversations: that is, without someone calling the cops or pulling out a gun. A reportedly 60+ million dollar deal with Chappelle likely pressured Netflix to conclude their partnership on friendly terms. Dave, however, took full advantage by doubling and tripling down on his earlier “cancel-able” missteps. He lampoons the Hollywood actresses who thought, “Let’s all go to the Golden Globes and wear black dresses and give these men a piece of our mind.”

“You think Martin Luther King was like I want everybody to keep riding the bus,” Chappelle rhetorically asks, “by wearing matching outfits?” As if the only thing these actresses could say was, “I want everybody to wear crochet pussy hats, so they know we’re serious.” No, he replies, “you gotta get off the bus and walk.” Dave ends by asking, “What the fuck was y’all doing?” He wonders, out loud, what feminism even means. Merriam-Webster defines feminism, he recites, as “1: the belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities” or “2: organized activity in support of women’s rights and interests.” Chappelle disagrees that feminism’s primary goal should be to secure equal rights or opportunities and leans more on feminism as an “organized activity in support of women’s rights and interests.”

Lean-in, or girl boss, feminism envisions a world where women have equal rights, but in practice merely suggests that women should have the same professional opportunities as men. But the world does not need more female billionaires; it needs robust wealth redistribution. Chappelle triples down by scolding LGBTQ+ allies and slacktivists for politically and sexually neutering their public displays or celebration of pride—to one month, each year, when soulless corporations compete for their attention and brand loyalty to expand their consumer base. Instead, Dave highlights the 1969 Stonewall Riots against police raids on gay nightclubs in NYC. For the next five days, hundreds risked their families, careers, and physical safety to protest.

On its one-year anniversary, thousands marched from Stonewall to Central Park and beyond, in America’s first gay pride parade; chanting, “Say it loud, gay is proud!” This civil rights based approach focuses more on ensuring the rights of minorities to, for example, peacefully assemble or to use the restroom that matches their self-identified gender; whereas the neoliberal-friendly approach to equal representation tries to boost the visibility of minorities and their token integration into the workforce. While I mostly agree with his take on performative “wokeness” is counter-productive, I can’t help but notice that Dave seems more like a social media gadfly now, rather than the comedian I once idolized for speaking truth to actual power—even when he chose to walk away from it.

The Gadfly of What, Exactly?

Despite his occasionally profound insight, Dave is no philosopher-king—he builds arguments from factual inaccuracies and misrepresentations. The rapper DaBaby, to use his example, killed another man in a Walmart with no negative effect on his career. But the moment DaBaby offended the LGBTQ+ community, Chappelle argues, he was swiftly canceled. “In our country,” he claims, “you can shoot and kill a n*****, but you better not hurt a gay person’s feelings.” Even more bafflingly, Chappelle ends his set by conflating those who end a man’s career or livelihood with taking their life. In reality, the only entertainers unable to at least partially recover from “cancellation” are those facing serious legal allegations. Yet for some reason, only the most famous and wealthiest comedians seem to obsess over cancel culture.

Comedians are still the closest, yet mostly estranged, heirs to Socrates who said, instead of wrote, what he believed was true without concern for the disbelief of others. Stand-up comics also directly address their audience in real time, except by telling their truth in the most surprising or incongruous way. Both “enlighten” their audience, but in two entirely different senses. Like Socratic dialogue, a stand-up set proceeds in a tightly choreographed series of premises or comedic beats that conclude with a punchline. Laughter is an individual, yet collective release of tension: generating instant and unfiltered feedback to a joke or bit, while rewarding the creative use of language to magnify, misconstrue, mislead, or aimlessly meander.

Stand-up comedy signals that it’s time to play with words, exaggerate body language, and engage the audience. Academic philosophers, by contrast, are the aristocratic descendants of Plato. Some of these temporarily embarrassed Philosopher Kings and Queens would rather engage with ideas than actual people—like their students, outside office hours. When addressing the greater public, they do so rarely and at a distance; from the vantage of their ivory tower. This insularity also untethers them from the expectation to entertain, as they critique institutional power, question social traditions, or disrupt cultural norms with novel points of view. As the true Gadfly of the State, only they can confront the more intractable or structural failures of capitalism, instead of merely observing or conveying the disparities it reproduces.

The most revered public intellectuals of the day, however, can not draw a fraction of the audience of a headlining comic’s audience. If legendary philosophers like Socrates, Spinoza, and Wittgenstein were correct—when they each reframed the prevailing philosophies of their time into a tool for therapeutic self-reflection—then no wonder comedians are now exponentially more popular. The darkest comedy, after all, can feel the most cathartic and enlightening. The audience can process their own anxieties and traumas by proxy. Rosebud Baker, for example, recently released her debut special, Whiskey Fists, which masterfully grounds her edgy comedy with intimate candor and insightful social commentary. For instance, Baker likens the right to abort 18+ years of potential child support with a gun owner’s right to stand their ground and protect themselves or their property.

Conclusion

Rosebud Baker’s decision to film her debut in Nashville is a testament to her ambition as a comic who prides themselves on performing in front of the most politically and demographically mixed audiences. Baker, for instance, begins by remarking that she recently started intermittent fasting, or what she calls “White people Ramadan.” With one off-hand joke, Baker slyly shows off her skill at punching up at minorities by instead punching down at herself for participating in the latest fad diet. From there, Whiskey Fists delivers blow after blow of Edgelord humor, which unexpectedly shocks her audience, before offering them some much needed comedic relief.

Baker even prefaces her closing joke by preemptively conceding that this is where she will likely lose the audience. Despite their playful or sarcastic undertones, both Chappelle and Baker defend Michael Jackson by more or less agreeing that any sexual abuse victim should be so lucky as to be groomed by someone with a sliver of his talent, generosity, or fame. A survivor of domestic violence, Rosebud tells straight guys to take a note from Jackson on romance.. In his previous special, Sticks and Stones, Dave Chappelle dismissed the sexual abuse allegations of two of Jackson’s victims: “…and even if he did do it,” he shrugged, “…you know what I mean?”

Actually, Dave, no—I do not know what you mean. In The Closer, for instance, Chappelle abruptly remembers ejaculating on a local priest’s face, but casually jokes it was okay despite being underaged, since he enjoyed it at the time. His off-the-cuff delivery makes it hard to know how seriously he intends to be taken. This “parallel thinking” reveals a disturbing motive behind the comic’s need to perform, which likely manifested around early social experiences. The sound of other people’s laughter grooms naturally funny people, until conditioned to always go for the laugh. Comics like Rosebud Baker pursue stand-up after becoming sober from drugs or alcohol: perhaps helping them process life as they “emotionally raw-dog” the world.

In contrast, almost all the stories told in The Closer seem to take place at some unappealing, remote bar. Instead of speculating on the lurid details of another person’s trauma, I conclude by rhetorically asking three questions: (1) What is Dave unable to emotionally process as he escapes with each drink he orders? (2) What compels a legendary comedian like Chappelle to forgo their personal or family time to instead go out, meet strangers, and chase the next fleeting moment of shared human connection? (3) And what will Chappelle find, as he sits down and reflects on his life—without having to pause for laughter?