by Ethan Seavey

On the Métro a man reads an ancient book. He cares for it greatly and flips each page with an abundance of caution. You know that it is ancient because the incredibly thin sides of each page have been painted an antique green and the page that he is reading is yellowed but in otherwise very good condition. The cover is a nice dark gray but it is too dark to read the title from where you stand clutching a pole, your body swaying and swinging and attempting to balance inside this skittish steel carriage. You know that he cares about this book because the dark cover reflects his fingertips. It is covered with a cellophane wrapper which implies that he has bought it just an hour ago from a Bouquiniste along the Seine and that he hasn’t brought it home yet where he would throw out the plastic. But he is deep within the book, hours, days into its story. He kept the plastic to protect it in a world as dangerous for an antique book as the Métro.

This man engages with his identity in a way that you fear. He’s seen: he is a literature professor in the making, the kind that leaves behind a stable life of business and begins to teach later in life. Today he’s too young and proud and primped to stoop to that salary. He wears a Hugo Boss mask and three layers of suit and tweed and pressed cotton. His shoes are as shiny as the cellophane holding the book and he is seen loving books and he is a bit unhappy. He turns and leans his forehead against the door and looks into the lightless tunnel flashing past. This tells his fellow passengers that they should expect his departure and a wordless goodbye and more space in the car and a subtly sentimental vacancy.

He is the essence of everything anti-American. For that he is precious and fills your brain with hopeful thinking: perhaps humanity is not so soiled by the digital age. Perhaps people are still being born with yesterday’s passions. You jot a character sketch in your journal, one that flatters even your glowing memory of him. You leave the train behind at Odéon and stroll to class, looking up at each identical Haussmann with wonder.

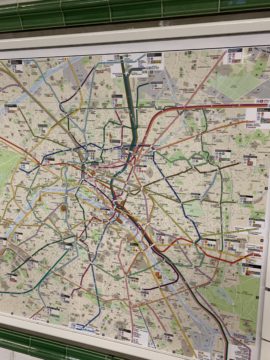

In Parisian classrooms filled with the students of New York I have heard a lot said about the difference between the Métro in Paris and the subway in New York. It’s faster; it’s more reliable; it’s cleaner; it smells better; fewer people board the train to serenade or evangelize the passengers but the ones who do are far louder and more determined; and, that the French look at their phones less than the New Yorkers do. I’ve heard it said that the French are more present and I’ve heard it said that they don’t run away from themselves like the Americans.

I’ve heard all of this said by American students who observe the Métro with the curious eye of novelty that often misleads us. When I first arrived I thought the same thoughts and I was mystified by the same book-loving man and I was so pleased to be in a world so occupied by the present reality.

But pull down your mask and smell the Métro—you will wrinkle your nose all the same. Rely on the train for a few weeks and it will make you late all too often. You will sit in a cloth seat that is wet with an ambiguous liquid. You will begin to notice that stealthy pickpockets that have replaced the loud beggars of New York.

Look beyond the young Frenchman with the book. Look at the few among the French who are not on their phones. Their eyes are too groggy to be busied with the screen’s light in the morning. Look at them, the exhausted ones who put their screens down and doze off into nothingness on their way home after work.

Look beyond these exceptions and you will see that the French use their phones as much as the Americans do. You will see every wire connecting their ears to their devices, white as the cracks on an old oil painting. You will see the faces buried in their phones and the people afraid to make eye contact with strangers. You will see the same people you saw in New York. There are not any less people obsessed with escaping their present, physical surroundings. What’s changed that they think in a different language and that you—the wide-eyed student who walks looking up at the Parisian windowsills—you are not looking down at your phone. You are in a fresh world and you are changing your relationship to your device for now. You see beyond the screen and notice only the people who do the same. But look at them, next.

A young woman with dark wavy hair and a nose that peaks at a miraculous summit prods her black wool scarf and looks up into the ceiling of the car. She sees beyond the metal roof and the thick layers of dirt above her head; she looks past Paris and up into its veil of grey clouds and scattered rain drops and then she bursts the atmosphere. She sees the world from a distance, as she often does when she forgets to stop herself. She shrinks herself to the size of an ant; there she is, burrowed underground, and she traces the path she takes from work to home and back again, a straight line to be retraced daily. She starts to sweat; and she picks up her phone and starts scrolling through Instagram. Her eyes anchor her mind to the phone and slowly she reels herself back down from space.

An old woman wearing a red ankle-length dress with bright yellow swirls sits in the corner chair and watches a show on her phone. You can tell by the pristine condition of the phone that she was reluctant to use it when she first bought it but now you watch her thumbs dance across the screen and you see that she has quickly adapted to using it every second she can. She watches it while she bathes at home and during her lunch break which she takes in a /parc/. When she is twenty years older and ready to die she will lie in the hospital and text her family across the sea that she loves them and she will turn off her phone and she will ask the nurse to turn on the TV. On the screen she will watch nurses in blue and doctors in white heal children and kiss each other and by the middle of the episode her mind will be in another world and her body will not realize it is falling asleep.She will only notice that the screen is shrinking but she will keep her eyes locked on it. The scenes retreat: a nurse-in-training guesses the mysterious illness; a doctor has an affair with a patient; an old North African woman lies on a moving gurney which crosses the background of a shot and she clutches her phone for comfort and calls her family who cannot come to see her and can only pick up and speak. And then she is gone.

It is the same on the Métro as it is the bus as it is for the RER B, the tram 3a, the lawn of the Eiffel Tower, the line before the rides at Disneyland Paris, the pastoral train to Reims, and the departures gates of Orly and Charles de Gaulle. It is the same in Dublin and on the bus to Galway. It is the same in Lisbon on the yellow creaking trolleys. And of course it is the same on the subway as it is on the El and the shuttle buses to the top of the ski mountain; skiers tap their icy cold screen, their gloves dangling from their wrists. It is the same wherever we were once bored and alone, now that we can be entertained and connected wherever we are.

Really, it is less that the people are so different here than that you are different there. Outside of New York you look up and project the world you want to see. On the faces of the dejected drowsy and depraved who aren’t on their phones, you create a people with an ancient and glorious history and a people unaffected by the shifting present. But the Métro is not so beautiful, and the subway is not so ugly, and they are not defined by how many necks are bent over screens. For every human silencing their thoughts with an endless stream of Tiktoks, there is a human who loves another human and wants to plan the future or just chat. When you look at a stranger on a phone, you assume that they’re running from the present; but they may be using this, the boring moment, to laugh with a friend far away or to look at photos of their grandchildren.

Instead look at how you spend your dedicated boredom. If you are mad about humans practicing escapism you probably see it in yourself. So do not pick the phone back up next year when you are back to the dirty, uninteresting subway. Find stillness or connection during the day, even if it’s in the chaotic world of public transportation. What defines you is not your relative location in the world now that distance has been conquered; what defines you is how you use your limited hours of boredom.