by David Oates

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

There it stays for some twenty hours – “as its crew tries and tries to fathom the trouble they are in.”

The ship is the Golden Hinde, and the captain is thus, of course, Sir Francis Drake – hero to every British schoolchild for the following four hundred-some years. Four hundred years of “gloating,” as author Horatio Morpurgo puts it, as he uses this pivotal moment to put some questions to the glittering hero – to its crew – and to ourselves.

Is Drake’s triumphant return to Plymouth harbor in September 1580 – the ship loaded with treasure – really all there is of this tale? It makes for easy telling, with Drake cast as the swashbuckling old sea-dog, as if from an Errol Flynn movie of the thirties. But what has been left out of this version? Morpurgo uses this daylong pause to ask the question: this episode of doubt ended in bitter enmity between the captain and his ship’s chaplain, who apparently preached against the great man – upon his own ship! – during these hours of peril. Why? What other stories are buried beneath the blinding treasures and easy clichés of the Golden Hinde?

“The Renaissance is an argument,” Morpurgo reminds us. A rage for new knowledge – a battle with tradition and authority (and anyone else who gets in the way). The beginning of science and the habit answering questions by observation. And equally the beginning of the long history of ravaging the earth for profit – at unimaginable cost to non-Europeans. And of course, as we now know, at unimaginable cost to the Earth itself: the beginning of multinational corporations, wealthy men chartered by monarchs to rip profits out of the world at any cost.

Four hundred and forty years of this process have landed us – we know too well where. A burning world we cannot quench because of the dead hand of profit-taking. National stories that make unquestioned heroisms of aggressions and brutalities. Morpurgo’s little book offers a strange and wonderful window through which to see into our national stories and ask deeper questions of them.

To demand, in fact, better storytelling. More accurate. And with, instead of self-congratulation, “complexity, substance, and human inflexion.”

Better storytelling as we, too, try and try to fathom the trouble we are in.

* * *

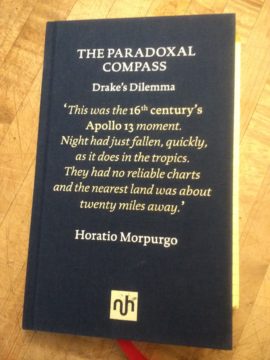

This essay is the third in a 3 Quarks Daily series about small press publishers. So before we return to the famous captain and his hour of doubt, a few words about this very charming book, with its hard cover of deep blue, its easy-on-the-hand size, its excellent paper, and its red bookmark-ribbon. It comes from the small press Notting Hill Editions, which publishes only nonfiction books.

From its website:

Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher founded by Tom Kremer (1930-2017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubik’s cube. After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to engage his passion for literature. In a digital world where time is short and books are throwaway, Tom’s aim was to revive the art of the essay and to produce exceptionally beautiful books that would be cherished.

We value quality over quantity, publishing only around six titles a year. In a world of overwhelming choice, our aim is to curate a library of fine writing and original thinkers, published in elegant editions. The books are brief enough to be read over a few evenings, but the ideas are timeless. (Kim Kremer, Managing Director)

All of the books are identical – of varying colors, but uniform in size, shape, and design. No time wasted in redesigning each new title. Instead, a focus on quality of writing, on insight and humanity and lasting content. Nothing faddish.

All of the books are identical – of varying colors, but uniform in size, shape, and design. No time wasted in redesigning each new title. Instead, a focus on quality of writing, on insight and humanity and lasting content. Nothing faddish.

Morpurgo’s book is a fine example, ranging far and wide, from present environmental disasters to the textual details of ancient voyages. This book about Drake is explicitly also about the present – what the great man’s story means to us, now. Morpurgo introduces discussion of a current issue, the overfishing and ecological degradation of Lyme Bay, in his home territory of England’s west country. There he participated with local environmentalists in a long campaign resulting in designation of the bay as a Marine Protected Area – a huge one, of some sixty square miles, later expanded to over a hundred. It was a signal success, and the first of its kind.

But in drawing in this example from the contemporary world, Morpurgo (characteristically) adds strikingly original historical context. He observes the degraded condition of Lyme Bay, brutally scallop-dredged and overfished for decades — the kind of thing most of us have unconsciously become accustomed to. But then he opens a window onto the deep past. He takes a look at a document from the 900s called Aelfric’s Colloquy – in which the medieval writer actually interviews fishermen, recording what they caught, in what quantities. Here is a deeper baseline to compare to, offering a chance for some “longer-range thinking.” And then Morpurgo adds information from the written records of the mid-eighteenth century “Exeter Whale Fishing Company.” This layered portrait of aquatic life in centuries past allows a suddenly acute sense of the current bay’s decline.

Modern-day ecologists talk about the problem of the “shifting baseline.” People are apt to think that whatever they see around them, and especially whatever they witnessed in their childhood, must be normal and thus “natural.” But what if that norm has been degraded slowly, over multiple generations? Who remembers? (No one. Except historians and ecologists). Mistaking their depleted environment as normal, folks can’t see what has been lost. Can’t imagine a powerful countermovement, valuing actual natural health over corporate profiteering.

That imagining is the work of a writer like Morpurgo: awakening the past, in order to awaken the present.

And in bringing out this brilliant nonfiction book and others of similar quality – Notting Hill Editions offers another instance of the crucial role played by the small and independent presses.

* * *

Morpurgo’s exploration of the Drake voyage is, as you’d expect, nuanced and full of texture and detail. He starts with portraits of three seafaring scientists contemporary with the famous captain: Stephen Borough; John Dee; and John Davis. In reading their stories we are reminded of the powerful renaissance motive of increasing scientific knowledge and accuracy.

Morpurgo’s exploration of the Drake voyage is, as you’d expect, nuanced and full of texture and detail. He starts with portraits of three seafaring scientists contemporary with the famous captain: Stephen Borough; John Dee; and John Davis. In reading their stories we are reminded of the powerful renaissance motive of increasing scientific knowledge and accuracy.

Such motives are usually left out by tellers of Drake’s tale. Or dismissed – with the shrug that really the voyage was “really” about geopolitics and money – Drake the privateer/pirate sticking it to the Spaniards and stealing as much of their silver as possible. Yet for Drake, Morpurgo insists, “the purpose of these voyages was as complicated as the age in which he lived.” The author asks:

How well have we been served by the cult of the cut-throat sea dog? Has it provided us with a useable, grown-up account of these people and the astonishing time through which they lived? One of the first things Drake did upon entering the Pacific was to observe a lunar eclipse. He supplied readings of magnetic variation in the southern hemisphere to a researcher, who in turn became one of the major influences on Galileo Galilei. He discovered open sea to the south of Tierra del Fuego. . . . To sum up the purpose of this voyage as a ‘pirate expedition’ will not do.

Reading the detailed portraits of the vivid intellects and explorations of these west-countrymen — Borough and the rest – is an unexpected pleasure of this book. Other heroes at work alongside the legendary Drake! All of them, in this telling, laboring to establish the habit of fact. What we would come to see as “science.”

In another surprise, we find that along with the empirical habit and the search for practical knowledge for navigation, we can see something very like nature writing also coming into being.

Drake’s pilot, the Portuguese Nuno da Silva, reports that the dreaded sea-dog captain also carried “a book in which he writes his log and paints birds, trees and seals. He is diligent in painting. . . .” Or as Drake himself described it, “seeing the wonders of the Lord in the deep, in discouring so many admirable things. . . .”

And the ship’s chaplain Francis Fletcher – who would later fall out with the captain – seemed to be pursuing a similarly “modern” take on the wide view of the natural world this voyage offered. His written account was called The World Encompassed but Fletcher was unable to find a publisher. It finally appeared a hundred years later, with illustrations.

With typical thoroughness, the admirable Morpurgo finds the original manuscript and compares it with the eventually published version. What he discovers is that the later version seemingly deliberately plays up the seafaring swashbuckle of the voyage. . . and removes other aspects. The scientific aspects. And the nature-loving aspects. Morpurgo quotes some of Fletcher’s ardent and vivid writing about the living creatures observed – penguins off South America for example, in his “rhapsodic, richly detailed style.” Or a long passage about flying fishes, quoted at glorious length. In the end, Morpurgo concludes simply:

This is nature writing.

I can tell you that “nature writing” as a genre is seldom back-dated to the renaissance. The big Norton Book of Nature Writing, resting on a shelf three feet from where I write, begins the story in the 1700s. As in most accounts, there’s mention of eighteenth-century English parson-naturalists, and then the real story starts with your Wordsworths and Bartrams and Audubons. Nature writing has always had this distinctly modern cast. (I cast myself that way too, at the beginning of my writing life – emulating Thoreau and Muir with all my might.)

So what an interesting complication it is, to discover this genre in the fifteen hundreds, in the precisely observed rhapsodies of captains and chaplains alike. At the beginning, in other words, of the modern era.

Sensitivity and receptiveness. The counterweight to all our moneymaking and strife. Read your Emerson, your Thoreau! The bliss of the natural world, co-existing then (as now) with privateering and treasure-hunting. Complicating the story, in other words, with complexity, substance, and human inflexion.

* * *

Interestingly, Queen Elizabeth’s secret service imposed a blackout on all accounts of Drake’s voyage which lasted decades. But this was slyly broken, in 1582, by the French botanist called Carolus Clusius, who interviewed shipmates from the Golden Hinde and produced an account of the voyage that did not seem to find it merely a military/commercial enterprise. The scientist was interested in other aspects of the voyage – the scientific and natural-history aspects. Directed to the developing international fraternity of science, the account slipped through the net of Tudor secrecy.

And this is the point of The Paradoxal Compass. Drake’s voyage, known to “every British schoolboy” as the saying used to go – should not be flattened to the shape preferred by the propagandists of the Tudor secret service. Nor, for that matter, to that preferred by statue-toppling purists of the moment. It had a life far richer, deeper, more human. And Morpurgo urges us: our hour of global disaster “demands, now, a fundamental retelling of the core stories about who we are.”

Only a new way of seeing that moment can finally make some benign sense of the global awareness it [the Renaissance] afforded us.

Trapped in the short-term, the author insists, we need the telling of longer stories. Richer, better stories. We must work to “deepen the truth.” (paraphrased from 173-75) For finding the humanity and complexity of these adventurers may help us recover our own.

* * *

Morpurgo’s larger aim in this book is to insist on the plenipotential richness of the past – the way it is never over, but only done and finished for those whose minds have closed tight around a cherished meaning, a glory or a depravity which they make their changeless pole star. “Over time this voyage has endured some very concerted attempts to force it into meaning two or three things and only those. It does not follow that those two or three things are all it meant.”

[A]nother historian . . . tells us in a BBC interview that Drake made his fortune in the slave trade, and that this is what he was knighted for. . . . He is condemning. But there is, again, no hint of doubt. [T]he champions and decriers. . . . talk straight past each other. My case in this essay is that they do not need to.”

In fact, as Morpurgo goes on to say, these damning claims about Drake are not facts. (He is a careful reader and historian, and I trust his assertion.) “We can piece together something more truthful.”

To vilify gets us no closer than the old sentimentalities did.

In our present moment, any hint of racial (or sexual) misbehavior may be enough to shut the books on a history. We are rightly sensitized to these immemorial wrongs. But if this sensitivity hardens into a kind of puritanism – a zealotry that thinks and sees only in black and white – then of course it will become just another code of imprisoning self-righteousness: the opposite of the larger mind that welcomes fact and revels in the world as it comes, imperfect and surprising.

Of course we must make the old stories whole and tell all parts of them, ugly or not. But “I’m not sure we need to set up new statues, or tear down the old ones. . . . I would rather that the old ones put us in mind of something new.”

* * *

It tickles me – always has – to think of the Golden Hinde on its voyage around the world finding its way to the coast of California. I’m originally a Los Angeles kid, and the thought of my state having this connection to Tudor England has always seemed just plain marvelous. Apparently it made landfall just north of San Francisco.

Morpurgo’s challenge to reconsider our national epics has me thinking about ours, here in the US. And as a transplant to the state of Oregon, I can report that here we never tire of the cross-country expedition of the Corps of Discovery, led by redoubtable Lewis and doughty Clark. But it is also very striking to me that, two hundred twenty years after Drake had visited the west coast of North America, newly minted “Americans” were still trying to find their way there.

Of course, the sea route to the west coast was well known. From, say, Boston, just sail five thousand miles south, round the Cape, then sail five thousand north again and bingo. But overland? Never been done (not by European-Americans, anyway). And so that is the great epic. How our scholar president sent a band of hardy men on a journey of discovery to Oregon. Jefferson, beloved author of “all men are created equal”! With his feet of clay reaching at least waist-high, implicated in slaveowning and slave-impregnating and, oh, it’s the American story for sure. He means so many things it makes us dizzy.

And looking at it with Morpurgo’s eyes, I see the Corps of Discovery itself escaping its caught-in-amber heroism, asking for more subtlety, more complexity. More humanity.

We’re apt, now, to remember that the hardy band soon inflected itself to include an indigenous woman – and her baby! – who literally saved the day more than once. And we’ve been noticing recently that an enslaved Black man was also a key member of the expedition – the renowned York, who was routinely mistreated by his “owner” Clark once the expedition had concluded.

The more you look at this patriotic saga, this boy’s-book adventure, the more complicated it becomes. Sadder and more hopeful, both.

When I take a few days off from my urban life in Portland, Oregon, I’m apt to find myself in the footsteps of the famous explorers. For close by my usual getaway town of Cannon Beach, a well-used trail snakes up through the rather drippy, mossy coastal forest of spruce and fir and hemlock – up and up onto the high cliff of a cape. With an hour’s hiking I can stand there and see roughly, mostly, what Meriwether Lewis and William Clark saw, when they took a reconnoitering journey themselves, walking south along the fir-drenched coast from their encampment at the mouth of the Columbia River.

I think about it every time. Now, at this writing, I notice that it’s been a nice symmetrical two hundred twenty more years since the odd couple heading the Corps of Discovery stood where I stand, gazing at the slate-blue horizon, the broad tawny curve of beach to the south, the dark little cape at its apex. . . the foaming rocks below, and the immemorial forest everywhere. What they meant, those brave Viewers – that’s what I ponder. Despite the years between us, the wars that have intervened, the money-mad cruelties, the vileness of our age and the greedy ignorance that is ripping our future to tatters. . . I want to recover some better story from them. I want to trust that it means – can mean – more than one thing.

Small things: the importance of a fiddle. And a Frenchman. And a little rum.

And larger themes. Hardiness. Adaptability. Diversity. Science. The open-endedness of the human story: not done yet.

As Morpurgo says: “It matters how we remember this.”

* * *

Our slave-owning heroes. What to do with them? A couple of decades ago I read the damning biography of Jefferson by Fawn Brody called Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate Biography. It outed the beloved president for his affair with the enslaved woman Sally Hemings. That was new (or newish) information at the time, shocking and troubling. Brody’s book spells it out.

Yet I remained, somehow, a Jefferson admirer. Couldn’t help myself. Recently the Jefferson Memorial in Washington DC was vandalized during the early nights of protests over the George Floyd killing. And just this summer, our local paper reported that “a group of about 15 people used ropes and an ax to topple a statue of Thomas Jefferson that stood on the front steps of Jefferson High School in North Portland. Four nights later, several dozen people tore down a statue of George Washington. . . .”

There was more iconoclasm to come. More outrage at the past, I guess. Portland features a city park on a volcanic cone inside our city limits, called by the biblical name of “Mount Tabor.” There’s a stand of tall swaying fir trees at the top, with benches to look out over downtown. And a bronze statue of prominent nineteenth-century Portland newspaper editor Harvey Scott. Which was duly pulled down. And then replaced, by a guerilla artist, by a bronzelike head representing York.

Which was itself, too soon, pulled down also.

As if we just cannot stand to be asked to think about anyone from the past. As if it’s just too hard, and the only thing to do is destroy the markers and reminders. Good guys and bad ones. Perps and victims. All pulled down. I think Lincoln got toppled in Portland too. Why not.

Surely a grown-up way of thinking about the past is to have done with the “heroes and villains” plot lines. History is not a cheap daytime drama. It’s the record of imperfection that leads to the present. The imperfect present.

Since I’m a recovering evangelical myself, it’s been useful for me to be nudged by my partner every once in a while, when I’m tempted to go into my High Dudgeon gear and do some heavy denouncing for some flaw or error in a friend or a public figure or, really, just about anybody. (The Jeremiad mode so dear to fundamentalists of all kinds.) Gently he reminds me, “No person is ever just one thing.”

Drake was many things. So was Clark. So were, and are, we all. If we are really interested in the human adventure, we’ll stay open to hearing the many stories, instead of fixating on just one (Hero or Villain) for all time.

I don’t want to have to give up Lincoln and Jefferson. Or Drake. Or even poor William Clark, who was so troubled and out of his depth in ordinary life that, once the expedition was over and he had served in a variety of appointed offices, he took his own life. The man who refused York his freedom also allegedly had a Nez Perce son and “served as a guardian to Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the son of Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau,” the expedition’s fiddle-playing Frenchman. Appointed at various times governor of Missouri Territory and superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, Clark became known (and widely criticized) for championing the rights of native tribes. Taken as a whole, that’s a story deserving of some sympathy, some awe perhaps, for its nearly Greek mixture of greatness and wretchedness. Terror and pity. And humanity.

Something any of us might learn from.

END