by N. Gabriel Martin

It had become harder to ignore the spectre of a decision looming on the horizon. After four years of temporary and part-time lectureships I couldn’t ignore the fact that the day that I would have to decide when to stop chasing a career with few rewards and fewer prospects was coming. Still, I always found it possible to put that decision off just a little longer.

That was fine with me, because I didn’t have any notion of how to face it. I knew that the time to decide was coming, but I couldn’t exactly tell what the decision was.

You would assume that it was the decision of whether to leave academia. But that’s only half a decision. What was missing was the other half – the “or …”

In the end I never came to a decision. Instead, the pandemic hit and the job market—already dismal—declined by three quarters. I never had to decide to let go, because the frayed ties that I still maintained to that career dissolved in my hands.

Fate nullified the choice I thought I would have to face.

When I was younger, and more driven by the need to master my own destiny, that might have been unbearable. I looked to the achievement of my own ambition to measure my life’s meaning.

I don’t think I’m unusual in that. The individualism of our age teaches us to treasure the satisfaction of our will. We tend to see ourselves as William Ernest Henley’s Invictus:

“I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.”

Today, fate is a deprecated value. We seldom find it possible to believe that the notion of fate has any meaning at all, and when we do give any thought to fate it is as nothing more than a thing to master.

But Henley is wrong: fate is not something to master. The indomitability of fate is something nearly every age has understood better than our own. Read more »

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

Tick, Tick . . . Boom! Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

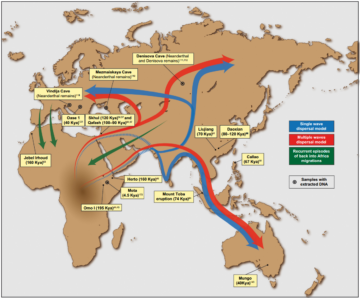

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.