by Fabio Tollon

From a heat dome in North America, people drowning in their basements in New York, and a climate famine in Madagascar, you would think we would have started to take the climate crisis seriously. This is to say nothing of the volumes of scientific evidence that support the theory that we are teetering on the edge of catastrophe and are in the middle of an extinction event. With this backdrop, you would be forgiven for thinking that an event with the purpose of addressing this crisis would propose significant changes to our current production and consumption patterns. As luck would have it, we seem to inhabit the worst of all possible worlds, where such a common-sense expectation is not met.

The 26th Conference of the Parties (or, COP26) promised much but delivered little. Before the event, there was a genuine sense that this might be a turning point in the fight against climate catastrophe: maybe world leaders could come to together and, for once, put the long-term welfare of our planet and those who inhabit it over short-term profit. Unfortunately, what emerged from COP26 was not very much of anything. Although the so-called Glasgow Climate Pact, agreed to at COP26, “moves the needle” it is nowhere near enough to stop global warming from exceeding the critical threshold of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (our current pathway is for an increase of 2.4°C).

What remains clear (and what was reinforced at COP) is that there remains a gigantic disconnect between what is needed to get a handle on the climate crisis and what is being proposed. Talks of $100bn in aid from the developed to the developing world fall far short of what is actually required. John Kerry, the chief American negotiator, echoed this point by claiming that it is not billions that we need, but trillions (between $2.6tn and $4.6tn, per year). Read more »

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry.

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry. What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are. Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

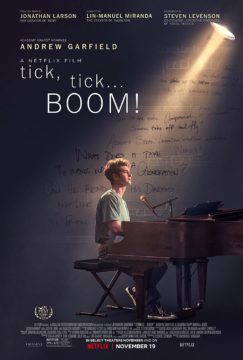

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!