by Joseph Shieber

More than any other, one article I read last Friday, June 24, brought home to me how difficult it is to maintain respect for the law in the face of injustice.

You’re probably thinking that it was one of the articles reporting on the United States Supreme Court’s having struck down the 50 year old precedent in Roe v Wade, constitutionally guaranteeing to women in the United States the right to exercise control over their own bodies. It wasn’t.

Rather, it was an article in the South China Morning Post announcing the death, on Friday in Beijing, of the lawyer Zhang Sizhi at the age of 94.

Zhang, known as the “conscience of the lawyers” in China, was born in Henan province in 1927. After serving for three years in the Chinese Expeditionary Force, Zhang began studying law in 1947, graduating from the Renmin University of China in 1950. Zhang was only able to handle a few cases in the 1950s before being thrown into a reeducation camp as a “rightist” and intellectual. He spent 15 years in prison.

After his release, Zhang resumed his legal practice and began a career as a defender of the developing Chinese rule of law – and the principle of the freedom to dissent – that spanned over thirty years, from the 1980s to the 2010s. Read more »

Some years after Carlos died, another friend and another noted development economist, Hans Binswanger, was diagnosed as HIV-positive. He initially took that as a death sentence and gave away much of the material things he had. But by then the new antiretroviral drugs were in use, and possibly because of them lived an active life for another quarter century, until he died in Pretoria, South Africa in 2017 at age 74. In 2002, shortly before he left his World Bank job, he founded and endowed an NGO in Zimbabwe, that supported about 100 mostly HIV-positive children and their families by providing education, supplemental health care, and counseling. In South Africa he married his boyfriend Victor in a traditional multi-day Zulu celebration. Since then he has always identified his last name as Binswanger-Mkhize.

Some years after Carlos died, another friend and another noted development economist, Hans Binswanger, was diagnosed as HIV-positive. He initially took that as a death sentence and gave away much of the material things he had. But by then the new antiretroviral drugs were in use, and possibly because of them lived an active life for another quarter century, until he died in Pretoria, South Africa in 2017 at age 74. In 2002, shortly before he left his World Bank job, he founded and endowed an NGO in Zimbabwe, that supported about 100 mostly HIV-positive children and their families by providing education, supplemental health care, and counseling. In South Africa he married his boyfriend Victor in a traditional multi-day Zulu celebration. Since then he has always identified his last name as Binswanger-Mkhize. Carved in marble above the entrance to the Supreme Court Building is the motto: “Equal Justice Under The Law.”

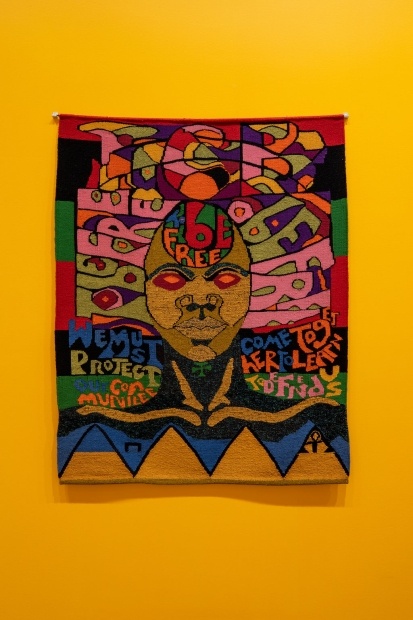

Carved in marble above the entrance to the Supreme Court Building is the motto: “Equal Justice Under The Law.” Napoleon Jones-Henderson. TCB, 1970.

Napoleon Jones-Henderson. TCB, 1970.

Dreams are about questions.

Dreams are about questions.

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

An Immense World; How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, Ed Yong, Random House/Bodley Head, June 2022

An Immense World; How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, Ed Yong, Random House/Bodley Head, June 2022

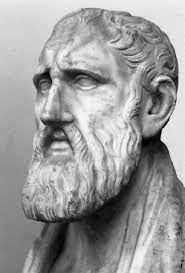

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.