by Mary Hrovat

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

My family went to the public library every two weeks, and there were books in the house, so I was given at best a mixed message about reading. I seized the opportunities offered by the books around me while evading the imposed limits. I read in the closet in the evening after my sister was asleep, or in the living room late at night when everyone was asleep. When I could, I read while I ate. Perhaps I was fortunate to have a boundary to transgress, ever so gently and passively, so as to avoid being entirely subsumed in the role of good girl.

I was reading to learn, but also to escape. Reading for escape is sometimes seen as an inappropriate use of time or a failure to accept reality. Look what happened to Emma Bovary and Catherine Morland (characters created by Gustave Flaubert and Jane Austen, respectively), who came to grief (in very different ways) by taking novels far too seriously. But escape from boredom, emotional distress, or anxiety is no bad thing. I tend to agree with W. Somerset Maugham, who said that reading provides “a refuge from almost all the miseries of life.” I was lucky this refuge was available to me. The power to escape into a book was a rare means of control over my circumstances, and I can’t imagine what life would have been like without it.

I read a lot of lightweight fiction as a child and teenager, in addition to escaping to other places and times. Even the most trivial of my reading, though, helped me overcome the parochialism of childhood, the assumption that the world I knew at home was basically the only world there was. Books taught me that there were other types of families, other types of parents, other religious views, other attitudes toward money and love and work. Each book was a glimpse into a different, sometimes previously unsuspected, world.

I wasn’t reading to broaden myself, because I didn’t realize, when I started, that I was narrow. I read because it was fun. Sometimes what’s labeled as “escapist reading” could more fairly be called “reading for enjoyment.” Having experienced prolonged periods of anhedonia, I value the act of reading purely for the pleasure of it.

Books as vessels. “There is no Frigate like a Book,” Emily Dickinson wrote, “to take us Lands away.” Books carry you toward as well as away from things. Sometimes they do both at once. If you’re reading to escape from ignorance or doubt, for example, you may not be sure where you’re going, but you’re seeking someplace different.

Books expand the horizon of those for whom one life is not enough. Even if I had unlimited money to travel, I couldn’t visit every place I’d like to see. Even if I could visit every place I’d like to see, I couldn’t know what it’s like to live there or to have grown up there. I can’t visit the past, live through the events of history, or travel to imagined futures. I can’t know historical figures personally, and I can’t live an ordinary life in any other time but this one. Books can carry me beyond these limitations.

People have a map and timeline of the world in their heads, and a rough outline of human knowledge. These tools are necessarily broad and imprecise over most of their range, more like sketches than in-depth views, and often incorrect about the details. It’s comforting that any point you choose on the map or the timeline, or any subject humans have studied, is usually much richer than you expect. The more I read (looking up words, names, place names, events), the more I realize how little I know. My reading lists are constantly growing. It’s the most satisfying receding horizon I can imagine, because there’s always a learning curve, a gradient to work against in pleasurable effort, an inexhaustible future. (The thought of an inexhaustible potential future, for someone with a limited lifespan, may seem cruel, until you consider the alternative.)

Built by books. I still tend to think of reading as a solitary activity that disconnects me from other people. In fact, though, reading is a form of limited but intense contact with another human mind. Carl Sagan wrote: ”One glance at [the page] and you hear the voice of another person, perhaps someone dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, the author is speaking, clearly and silently, inside your head, directly to you.”

Patrick Leigh Fermor, in A Time of Gifts, spoke to me of passing through Rotterdam late in 1933, at the very beginning of his journey on foot to Constantinople (as he still referred to Istanbul). After describing the Grote Kerk in Rotterdam, he wrote that except for that church, the city was “bombed to fragments” during the war. He added, “I would have lingered, had I known.” That sad and lovely sentence immediately became a nexus in my mind connecting scattered thoughts associated with regret and the irrevocability of the passage of time.

Other sentences gradually fall away. I was introduced to countless concepts in mathematics, physics, and astronomy when I was an undergrad. For example, Paul Tipler, in his textbook Modern Physics, informed me that “The rest mass of a bound system is less than that of the separated particles by Eb/c2, where Eb is the binding energy.” I don’t remember reading this. As I attended class and read further in the book (into chapters where the idea of binding energy was developed further) and used this information to solve problems, the words were replaced by a mathematical understanding and ultimately a concept embedded in my mind. Until I looked at my old textbook, I couldn’t have put a name to the writer who put this information into a book so I could refer to it. The book itself seems to represent a very abstract and impersonal transmission of knowledge. But by presenting this concept to me, Tipler enabled me to communicate with other people.

Sometimes a writer conveys a powerful image in addition to factual knowledge. A few days after my grandmother’s funeral, I stumbled upon Loren Eiseley’s book The Firmament of Time, which I pulled from a shelf in a tiny library because the title was so beautiful. As I flipped through it, I happened upon a description of an intentional Neanderthal burial at La-Chapelle-aux-Saints in France: “Massive flint-hardened hands had shaped a sepulcher and placed flat stones to guard the dead man’s head. A haunch of meat had been left to aid the dead man’s journey. Worked flints, a little treasure of the human dawn, had been poured lovingly into the grave.” When I read those words, I remembered my family dropping long-stemmed roses onto my grandmother’s casket after it had been lowered into the ground. Eiseley’s image put my family’s loss and my grief into a much wider context.

The written word waits for you to be ready for it. In her 1976 essay “The Space Crone,” Ursula Le Guin wrote about postmenopausal women. I read this essay very recently and was electrified by the mysterious but potent suggestion that a postmenopausal woman consider “becom[ing] pregnant with herself, at last.” I was a teenager when Le Guin wrote this, and at the time, I probably didn’t know who she was, but decades later, her words came to me when I could use them. Who knows what other human experience has been captured in words and stored away by others, and may come to my hand and eye in a time of need?

Books as fading human traces. Without a reader, the meaning and energy of the printed word are latent, present only as potential. Readers can be seen as acting in collaboration with the writer, re-creating a book by bringing the dark and silent pages to life. Rebecca Solnit, in her essay “Flight,” emphasizes the intimacy of the connection between writer and reader: “A book is a heart that only beats in the chest of another.”

Books as fading human traces. Without a reader, the meaning and energy of the printed word are latent, present only as potential. Readers can be seen as acting in collaboration with the writer, re-creating a book by bringing the dark and silent pages to life. Rebecca Solnit, in her essay “Flight,” emphasizes the intimacy of the connection between writer and reader: “A book is a heart that only beats in the chest of another.”

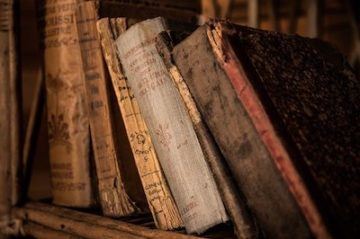

According to Milton, “Books are not absolutely dead things.” But because books require readers in order to be fully alive, they sometimes seem to be clinging to a precarious existence, and then they are at their most poignantly human. I think of this when I’m looking at the oldest books at our local book sale, the ones that perhaps haven’t been re-created in the mind of a reader for a long time. I imagine them as faint lights in the collective human consciousness, on the brink of disappearing into darkness.

Of course, with books as with people, none of them last forever. Still, it’s easier to accept this in the aggregate than in the case of any particular book or person. In “The Poet and His Book,” Edna St. Vincent Millay expressed a poet’s belief that her death would occur, not when her body failed, but “When this book, unread / Rots to earth obscurely.” The poem continues with an impassioned plea to a possible reader: “Read me, do not let me die! / Search the fading letters, finding / Steadfast in the broken binding / All that once was I!”

###

The quote from Penelope Lively comes from her novel How It All Began. The essay by Ursula Le Guin appears in her book Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. The quote from Milton comes from his poem “Areopagitica.” The essay by Rebecca Solnit appears in her book The Faraway Nearby.

###

You can see more of my work at maryhrovat.com.

First image by Pexels from Pixabay. Second image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay.